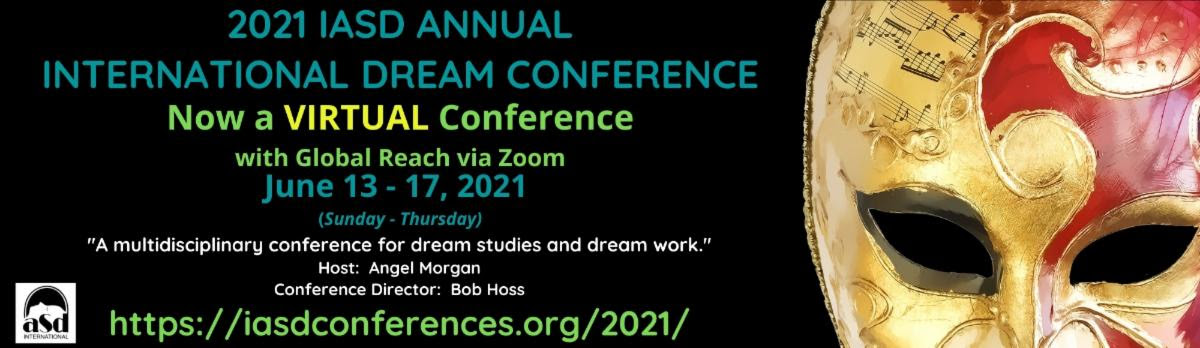

It is remarkable how many books about dreams have been published in recent years. In part, this is the result of the efforts of the International Association for the Study of Dreams, which has created a world-wide network that has linked dream scientists, dream therapists, dream artists, and dreamers with no qualifications other than their interest in the topic. One would have thought that everything that could be written about dreams had already found its niche in publishers’ catalogs and people’s bookcases.

Not quite. William Stimson has produced a unique personal account of how dreams shaped his life, taking him on a heroic journey that will serve as a manual for many readers who desire to use their dreams as a vehicle for their own spiritual, emotional, intellectual, and creative development.

Stimson’s book delves deeper than other treatments of dreams. He shows how the current scientific paradigm of reductionism permeates many dream studies, with its emphasis on the chance evocation of images resulting from neurochemical reactions. Instead, he takes a non-linear, non-psychoanalytic approach. From this perspective, dreams come when they are ready to come. With a few exceptions, dreams are not under the dreamer’s control. Dreams reflect the reality of the dreamer’s everyday life, often revealing a crossroads and the path best chosen. This is why they served adaptive purposes over the millennia and this is why they are worth pondering. Dreams actually cooperate with dreamers in the hundreds of thousands of years that homo sapiens has lived on this Earth, and the earlier millennia when earlier species presaged what became nightly dream narratives.

From an autobiographical perspective, Stimson traces his interest in dreams to early contact with a Cuban curandero, a search for wild orchids, a foray into the composition of Spanish music, and his avid perusal of Lao Tzu, Chang Tzu, Socrates, Carl Gustav Jung, and – more recently – Montague Ullman. It was Ullman whose inspired dream appreciation method led to the formation of the International Association for the Study of Dreams and whose experience as a psychoanalyst convinced him that dreams are best interpreted by dreamers themselves, albeit it in a supportive setting where obscurity gives way to insight and where confusion turns into clarity. Self-acceptance, more than any other trait, is the key to Ullman’s method, and can lead to a lifestyle that infuses emotions, thoughts, and behavior during one’s waking hours.

One might say that this paradigm is what the world needs now, and the philosophy of Ullman’s method is appropriate to this time. The torn fabric of today’s world can be mended by those who dare to dive deeply into their own unconscious, indeed into the collective unconscious, to find the connecting threads that will harmonize with the cosmic dance, and keep participants in the human drama alive and thriving for some time to come.