ABSTRACT: According to Gavin Arthur's 'circle of sex' model, all humans fall on a continuum that allows for fluctuation in sexual disposition as well as the intensity of sexual activity. His typology of human sexual behavior avoids such pejorative labels as 'abnormal', 'deviant', and' pathological', and introduces the terms 'heterogenic', 'homogenic', and 'ambigenic' because such terms as 'heterosexual' incorrectly combine Greek and Anglo-Saxon roots. Arthur illustrates his model with historical characters; for example, George V of England, the faithful husband of Queen Mary, fell at 12 noon, but Julius Caesar, known in his day as 'every woman's husband and every man's wife' fell into the 'ambigenic category'. Sappho, the poet who lived on the island of Lesbos, was described as 'three quarters homogenic' because, although she preferred Lesbian girls, she occasionally dallied with young shepherds. The writer Gertrude Stein was categorized as 'homogenic' at 10 o'clock. Arthur denoted sexual intensity by putting someone in the sphere's tropical center. Someone who has taken religious orders, however, might find himself or herself near the chilly regions of the circle. A Roman Catholic nun, who considers herself 'married to Christ', could be a 6 o'clock 'heterogene". The psychiatrist, Jean Bolen, developed a model that paid special attention to the sexuality of the Greek gods and goddesses. But instead of using their sexuality as the basis for a typology as Arthur did, Bolen focused upon the deities as representing 'archetypes', 'powerful inner patterns that allegedly shape behavior and influence emotions. In other words, there can be gay Ares types and lesbian Aphrodites because the archetypes they represent are broader than sexual preference. This typology may be more useful to psychotherapists than Arthur's ingenious 'circle of sex'.

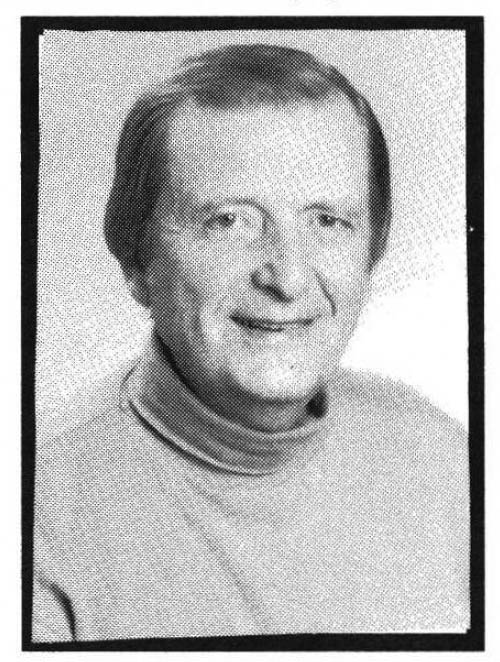

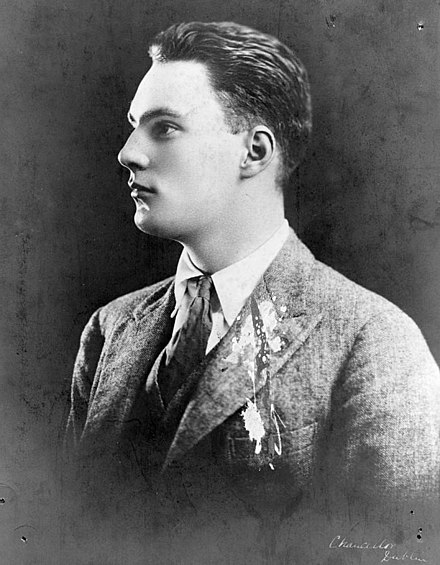

Chester Alan Arthur III (better known as 'Gavin Arthur') was the grandson of the thirty-second president of the United States. Although a president's grandson and a millionaire's son, he worked his way around the world as a Merchant Marine, observing a variety of cultures along the way. This exposure to the varieties of human experience is reflected in his book, The Circle of Sex (Arthur, 1966), which introduces a typology of human sexual behavior that avoids such pejorative labels as 'abnormal', 'deviant', and· pathological'. Noting that the adjectives 'heterosexual' and 'homosexual' are etymologically incorrect because they combine Greek and Anglo-Saxon roots, Arthur substituted the terms 'heterogenic' and 'homogenic'. According to Arthur, all humans fall on a continuum that allows for fluctuation in sexual disposition as well as the intensity of sexual activity.

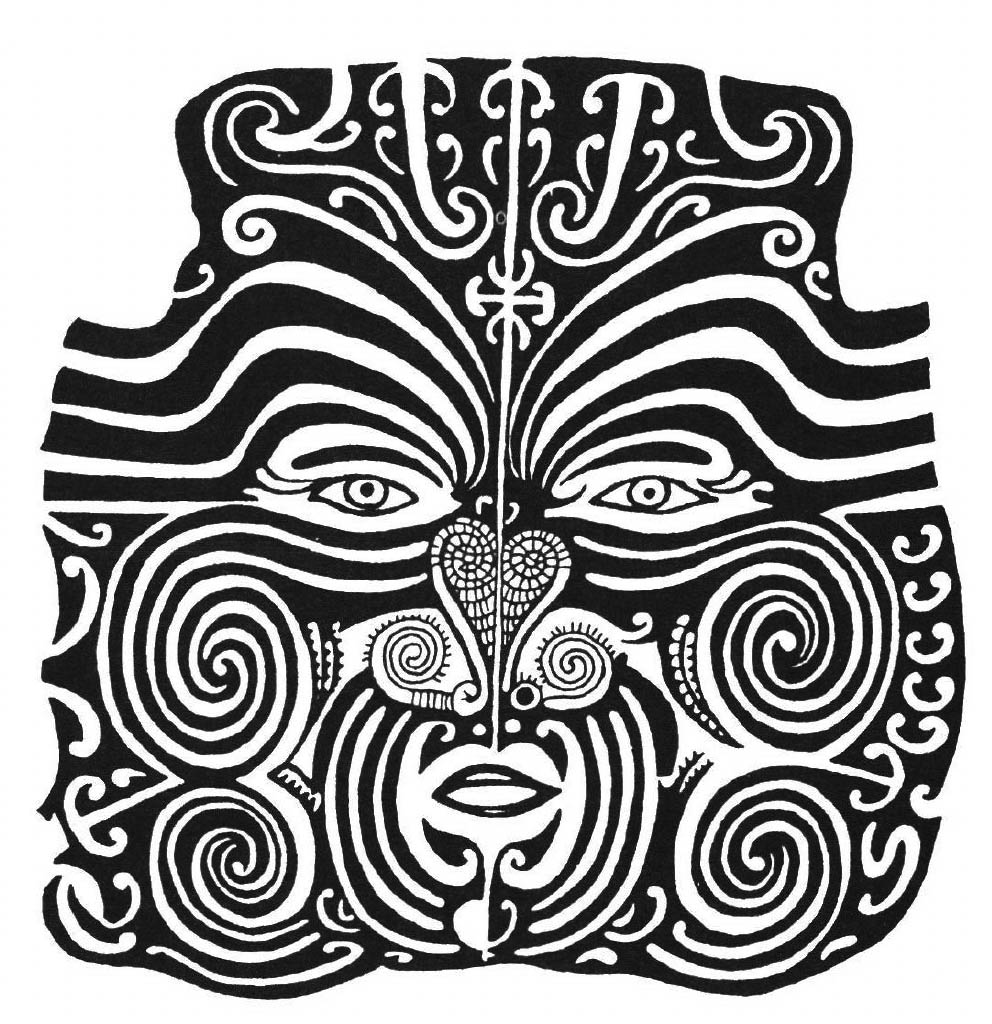

Using a clock as the template for his typology, Arthur put George V of England, the faithful husband of Queen Mary, at 12 noon. Lord Nelson, who adored Lady Hamilton but asked the naval officer who was next in command to kiss him as he lay dying off Trafalgar, was placed at 1 o'clock, and was classified as 'three-quarters heterogenic'. At 2 o'clock, Julius Caesar, whose sobriquet was 'every woman's husband and every man's wife', fell into the 'ambigenic' category, while Lord Kitchener, at 3 o'clock, was classified as 'three quarters homogenic' because he preferred young soldiers to the women of the English court.

At 4 o'clock, Arthur placed the poet Edward Carpenter, the best known disciple of Walt Whitman; Carpenter had no sexual interest in women and fell into Arthur's 'homogenic' category. Catherine the Great of Russia, who lamented that she could take only five men to bed at a time, was categorized as 'hyperheterogenic' at 5 o'clock. Queen Victoria, archetype of the faithful wife, was classified as 'heterogenic' at 6 o'clock. Arthur considered George Eliot, the English author, at 7 o'clock, as 'three-quarters heterogenic', while, at 8 o'clock, the First Duchess of Marlborough was considered 'ambigenic' because she slept with both her husband and England's Queen Anne.

Arthur's 9 o'clock example was Sappho, the poet who lived on the island of Lesbos. She was 'three quarters homogenic' because, although she preferred Lesbian girls, she occasionally went for a romp with young shepherds. At 10 o'clock, the writer Gertrude Stein was categorized as 'homogenic', and reportedly gave Arthur her personal approval of this categorization. France's King Louis XV, at 11 o'clock, was 'hyperheterogenic' because he had mistress after mistress, both before and during his reign.

Sexual intensity was denoted by Arthur by putting someone in the sphere's tropical center, as was the case with literature's don Juan, at 11 o'clock, and Lady Chatterley, at 5 o'clock. Someone who has taken religious orders might find himself or herself near the chilly regions of the Circle of Sex. A Roman Catholic nun, who considers herself 'married to Christ', could be a 6 o'clock 'heterogene', far away from the internal regions of overt passion. Thus, one's position in any of these 12 categories does not necessarily imply that one has an active, overt sex life.

Folklore and Mythology: From 12 o'clock to 6 o'clock

Diel (1980) sees mythological deities as 'idealizations of human qualities' (p. 173) and legends as providing such lessons as 'the inability to make the right choice of partner and establish a lasting relationship' (p. 145). Hence, mythology and folklore (e.g., Guirand, 1968; Middleton, 1967; Sullivan, 1988) provide a unique cross-cultural opportunity to apply Arthur's typology. For example, the central axis of his Circle of Sex is 12 o'clock opposite 6 o'clock where Arthur placed the faithful husband Darby and his loving wife Joan. Darby and Joan are featured in an old English folk ballad, 'the Happy Old Couple'; they were monogamously married and managed to live their lives more or less harmoniously. Two similar' heterogenes' were Philemon and Bacchus, the endearing couple visited by the Greek gods Zeus and Hermes. Philemon and Bacchus' hospitality was so impressive that upon their death, Zeus transformed them into intertwined vines.

The Greek earth goddess Gaia and her husband Uranus may well fall at 6 o'clock and 12 o'clock, as would the Hopi earth mother A'witelmn Tsi'ta and Apoyan Tachu, the sky father. Another famous pair was Geb and Nut, the Egyptian deities of heaven and earth. Playing against stereotype, Geb was the sky goddess, while her husband (and brother) Nut was the earth god. They are generally pictured in a circular form with their son, the god of air, drifting between them. The Incan sky goddess was the Mother Moon, Mama Quilla, and her husband was the sun god, Inti. This couple helped the Incas calculate time, plan their festivals, and regulate their calendar. A less benevolent coupling consisted of Michtlantechuhtli and Michtlantecihuatl, the Aztec lord of death and his consort, the death goddess.

'Heterogenes' who were monogamous, even if their wives were not, could be placed at 12 o'clock; Hephaestus, the Greek god of crafts and the forge, was faithful to Aphrodite, even though his wife had more sexual liaisons than any other Greek goddess. 'Heterogenes' who were not monogamous would probably fall at 12 o'clock, as long as they enjoy the company of men as well as of women. Among them are Ares, the Greek god of war who had numerous liaisons with women, and Xango, the Candomble god of thunder, who was married three times.

Although the celebrated perpetrators of mother-son incest could find their place at a number of spots around the circle, many of them would resemble the 'heterogenic' males who end up at 12 o'clock (and the 'heterogenic' females at 6 o'clock). These would include tragic, guilt-ridden figures, as well as those who are considered heroic. For example, the Greek king Oedipus unwittingly married his mother after killing his father, putting out his eyes when he discovered their identity. The Candomble deity Orungan ravished his mother, Yemanja, who then gave birth to a dozen children as well as the sun and the moon. In one version of the Aztec myth about their mother goddess, Coatlique's husband physically abused her until one of her (several hundred) sons took action, killing his father and becoming his mother's lover. The South American Panare mythology contains an example of father-daughter incest: Whenever the Sun and his daughter the Moon have intercourse, there is a total eclipse. In addition, there is the Banima myth of Kuai, whose father Inapirikuli impregnated her, a birth ritualized in the 'battle of the flutes' (Sullivan, 1988, p. 217).

A prime candidate for the 1 o'clock spot would be the 'mostly heterogenic' Zeus, the Greek king of the gods. Zeus, who occasionally dallied with handsome human males, was so sexually voracious that he would be positioned near the boiling center of the circle, in other words, at the torrid 'heat' of sexual passion. Poseidon, the Greek god of the seas, was not far behind Zeus in his sexual proclivities. He ravished numerous women including the goddess Demeter. He raped Amphitrite, although he latter married her. In addition, Poseidon took Pelops, the son of Tantalus, to Mt. Olympus as his paramour.

Achilles, a husband and father at the time of the Trojan War, fell into a rage when his lover Patrocles died in battle; the Greek hero went on a rampage and killed Hector, the Trojan prince who had killed Patrocles. Noah's son Ham begot a prominent lineage of descendants; however, a reading of Genesis IX: 20-21 reveals that he 'saw the nakedness' of his father, a phrase that can be translated as having sexual relations with someone.

A candidate for the 2 o'clock position would be the 'ambisexual' Balinese god, Syng Hyang Toenggal; it is believed that he can switch sexes in an instant (Highwater, 1990). A Nordic equivalent would be the 'twogendered' Ymir, whose sacrifice was necessary for the creation of the Earth (Bjarnadottir, V.H., & Kremer, J ., 2000). Hermaphroditus, the son of Aphrodite and Hermes, is a hermaphrodite, giving his name to those whose physiology incorporates both male and female sex organs. However, he lives near the cold outer regions of the Circle of Sex, being indifferent to lovemaking. Ometecuhtli, the 'ambisexual' creator god of the Aztecs, is also hermaphroditic, giving birth to the deities of the four directions. Candomble, an African-Brazilian religion, venerates Oxala, the 'ambisexual' god of purity. However, his sexual encounters are rare and he also would inhabit the chilly outer areas of 2 o'clock. Closer to the red hot center would be Hermes, the Greek messenger and trickster known as the 'cunning deceiver'. A lover of both men and women, Hermes had several sons including Pan, the satyr.

At 3 o'clock we could suggest Apollo, the Greek god of music and the arts. His love affairs with women amounted to fiasco after fiasco. Daphne, Sybil, Marpessa, and Cassandra rejected him, he murdered Coronis in a jealous fit, and he killed Hyacinth in a discus-throwing accident. But Apollo did little better with men; the love of his life was Hyakinthos, a beloved lad he killed in another accident.

The 'homogenic' Greek mythic figure Ganymede, Zeus' cupbearer as well as one of his male lovers could be placed at 4 o'clock. It is said that Zeus gave Ganymede's father a golden grapevine and/or a pair of horses in exchange for his son. Ganymede eventually was immortalized as Aquarius, the water bearer of the heavens. Other candidates for the 4 o'clock position are Aphroditus, the male aspect of Aphrodite, the Greek goddess of love, and Asterion, the Minoan patron of men who love men. Asterion's black hide was mottled with the stars of the universe, and he was regarded as both the 'Bull of Heaven' and 'The Starry One' (Garon du, 2002).

Erzulie, the 'hyper-heterogenic' goddess of love in Haitian vodoun, might find her place at 5 o'clock; this lovely lady had numerous male lovers, many of whom betrayed her or treated her badly. Erzulie suffered from t his treatment, but her sorrow endears her to her human followers. Other goddesses at 5 o'clock would include Aphrodite, Venus, Tlazolteotl (the Aztec goddess of love and pleasure), and Oxum (the Candomble goddess of the sweet waters). All enjoyed the company of men, preferring their camaraderie to that of women. Athena, the goddess of wisdom and learning, also preferred the company of men as friends and mentors, but stayed at the cold outer regions of the circle rather than nearer to the torrid center to preserve her virginal status. One of her favorite companions was Pallas, but she accidentally killed him during a sports event.

As mentioned earlier , such 'heterogenes' as Joan, Geb, Gaia, and Bacchus (the wife of Philemon, not the god of wine with the same name) would probably find their places at 6 o'clock. At 6 o'clock we also could place Hera, goddess of marriage and the wife of the lascivious Zeus. She once left her husband in a tiff, but Zeus announced that he would marry a local princess. Actually, he arranged a mock ceremony with a statue; when Hera discovered the ruse, she was amused and forgave her errant husband.

Radha, the frequent consort of Krishna (himself an incarnation of Vishnu), is another 'heterogene' who could be placed at 6 o'clock, as could Izanama, the ancient Japanese goddess who, with her consort Izanagi, begot the countries of the world. Sometimes these couples fit so closely together than their children have to separate them for creation to take place; the Maori sky god Rangi and the earth goddess Papa were split apart by their son, Tane, to bring light to the people of the world. The Egyptian deities, Nut and Geb, were separated by their son, Shu, the air god, to provide some 'breathing space' for the survival of earthly inhabitants.

Folklore and Mythology: From 7 o'clock to 11 o'clock

At 7 o'clock, we need a candidate who is 'three-quarters heterogenic' and the Norse goddess Freya, goddess of both the hunt and of love, might fill the bill. Although married to Odhur, She was especially fond of the Nordic elves, primarily the diminutive male creatures; but there are hints that she enjoyed occasional female elves as well.

At 8 o'clock we might find Oxumare, the Candomble goddess of the rainbow. The daughter of Oxala and Nana, Oxumare changes from female to male or from male to female, every 6 months. Many of the ancient 'Great Goddess' figures of Europe seem to have been androgynes, the male part becoming the fertilizing power, and the female part, the generating womb (Bjarnadottir & Kremer, 2000, p. 154). We could also place the Greek goddess Teresias at this posit ion. Although she was blind, the Greeks believed that Teresias' ambisexuality was the source of her great wisdom and insight. As was the case at 2 o'clock, we find both androgynes (e.g., the two-gendered Ymir and 'Great Goddess') and ambisexuals (e.g., Oxala, Teresias) in this cluster, as well as those deities (e.g., Syng Hyang Toenggal, Oxumare) who are able to switch genders periodically.

At 9 o'clock, we could enter many of the Candomble pombajeiras who are 'three-quarters homogenic'; these female 'exus', or tricksters, often have sex with each other as well as the mortals who fall victim to their tricks. Some of these entities have been identified as Pombajeira Cigna, Pombajeira Mary Molombo, and Pombajeira Diana. As noted earlier, Sappho falls at 9 o'clock. Although well known for her love of women, one account claims that she threw herself into the ocean when the handsome Phaon spurned her.

At 10 o'clock, a logical entry would be Ares' daughter, the Amazon queen whose name was variously given as Penthesileia or Hippolyta by the ancient Greeks. Artemis, the Greek goddess of the hunt, avoided the company of men, and her priestesses, the Arktoi or 'she-bears', wore phalluses. However, there are no tales of sexual congress between Artemis and the Arktoi, and so this goddess would be a likely candidate for 10 o'clock's frosty regions. Hestia, the virginal goddess of the home and hearth, avoided the company of men, but was not involved sexually with her female companions, nor were the Nordic Valkyres, most of them warlike virgins.

Even though he once seduced a young male ward of Athena in a drunken debauch, the Greek god Dionysus was 'hyper-heterogenic' and probably falls at 11 o'clock, giving his name to the 'Dionysian revels'. The only male Greek god who preferred the company of women to that of men, Dionysus eventually fell in love with Ariadne and remained faithful to her. Before that, he actually drove women who resisted him into madness, but later restored their sanity when he recovered from the rejection. Krishna, whose 'wanton rapture' of the Gopis (i.e., cowherders) is the topic of many Hindu legends (Campbell, 1962/1982, p. 344), also is placed at 11 o'clock. His love affairs with the Gopis were nocturnal events, and they returned to their husbands the next morning, convinced that their union with Krishna took place in a dream.

Conceptual Issues

In this essay, the nouns' homosexual', 'heterosexual', and 'bisexual' are not used to describe any of these characters because these terms are fairly recent social constructions. Until the end of the 19th century, there was 'homosexual behavior' etc., but the perpetrator was not called a 'homosexual'. At this point in time, various European investigators began to explore human sexuality and labeling was initiated. The ancient Greeks and Romans, and the contemporary Haitian and Brazilian adepts, would not think of confining their deities with a label!

Arthur's Circle of Sex may seem comprehensive, but it does not cover those deities who enjoyed sexual congress with non-humans, e.g., the Eskimo goddess Sedna took a bird-spirit as her lover. And some deities are not human, e.g., Amaru was the water snake mother goddess of Banima mythology. Nor does it discuss characters who had sexual reassignment operations; according to the Mahabarata, Sekhanda was a women who persuades a demon to change her sex so that she can join the army to fight her nation's enemies. Furthermore, some deities transcend gender; in Hopi mythology, Awonawilona is 'The Maker and Container of All'. but no reference is made as to gender. In addition, there are several versions of each myth, making rigid classifications dubious. In one Greek myth, Aphrodite was born as the result of a dalliance between Zeus and the sea nymph Dione. In another, Cronos cut off the genitals of his father Uranus, throwing them to sea; Aphrodite was born from the union of the water and the sperm.

Jean Bolen (1984, 1989), a Jungian psychoanalyst, has also paid special attention to the sexuality of deities, primarily the Greek gods and goddesses. Instead of using their sexuality as the basis for a typology as Arthur did, Bolen focuses upon the deities as representing 'archetypes', defined as 'powerful inner patterns [that] shape behavior and influence emotions' (1984, p. 2). This psychological perspective is 'based on images that have stayed alive in human imagination for over three thousand years' (p. 2). A culture's social stereotypes 'reinforce some patterns and repress others' (p. 4), but knowledge of these archetypes can assist individuals on their 'individuation journey' (p. 93), held by Jungians to be one's life goal.

In other words, there can be gay Ares types and lesbian Aphrodites because the archetypes they represent are broader than sexual preference. In addition, the differentiation between 'sex' and 'gender' helps to avoid stereotyping; 'gender' resembles the Chinese use of the terms 'yin' and 'yang' rather than 'male' and 'female'. It helps to explain the presence of 'earth fathers' (e.g., Nut) and 'sky mothers' (e.g., (Geb) in mythology and folklore; the archetypes of 'penetration' and 'receptivity' go much deeper than one's physical sexual characteristics.

According to Bolen (1984), an Artemis woman can be lesbian or not, frigid or not, monogamous or not; all these Artemis types see work as more important than relationships, and have a sense of affiliation with other women, professional or social. According to Bolen, if the Artemis woman is a lesbian, she is usually part of a lesbian community or network' p. 60). In addition, there are single Athenas, married Athenas, and lesbian Athenas. All of them lack a kinship with other women, and see sex as a calculated art-as part of a broader agreement to attain some goal. Diel (1980) finds archetypal betrayal patterns in Jason's treatment of Medea, Theseus of Ariadne, and Siegfried of Brunhild. There are also false betrayals, such as Shiva's discovery of a man watching his wife bathe; only after he beheaded the offender did he discover that this was his own son, Ganesa. Shiva's promise to replace it with the first one available resulted in Ganesa's elephant head.

Parker (1996) asked some 200 women to profile their' goddess characteristics' on a checklist, to respond to pictures of goddesses, and to discuss their feelings about the goddess concept and its implications for their lives. The results appear in Parker's book Goddess Power, which, for example, states that 'the Aphrodite archetype falls in love easily and often [but] Judeo-Christian, Muslim, and other patriarchal cultures tend to picture such a woman as a temptress, adulteress, or simply a whore' (1996, p. 77). Thus, social stereotype conflicts with archetype, and Bolen (1984) characterizes as 'in between' the women caught in this conflict.

Parker suggests that goddess profiles can change over time, and his checklist provides an instrument for conducting research on this topic. This change is not necessarily for the better. Parker compares one's temperament, which resists change, to computer 'hardware', while the 'software' of social conditioning comes from external sources. Thoughts, feelings, and behaviors result from the interaction between 'hardware' and 'software', i.e., between archetype and social stereotype. If a marriage is based on social stereotypes, and if one partner reverts to an archetype, the marriage may fall apart. Parker provides sample 'goodbye letters' written by seven different goddess-types, the common denominator being 'you never really knew me' (pp. 180-181).

In other words, Gavin Arthur's Circle of Sex, as well as other attempts to connect cultural myths with personal myths (e.g., Feinstein & Krippner, 1997) have implications for contemporary behavior. There are several human characteristics that appear to be genetically 'hard-wired' and we ignore them at our peril. Ancient and indigenous people recognized these traits, exteriorizing them in myths, legends, and folktales. This storehouse of wisdom is now the common property of all humankind, and provides a rich legacy for our continued learning and instruction.

References:

Arthur, G. (1966). The Circle of Sex New York: University Books.

Bjarnadottir, V.H., & Kremer, J. (2000). Prolegomena to a cosmology of healing in Vanir Norse mythology. In S. Krippner & H. Kalweit (Eds.), Yearbook of cross-cultural medicine and psychotherapy 1998/1999 (pp. 125-174). Berlin: Verlag fur Wissenschaft und Bildung.

Bolen, J. S. (1984). Goddesses in Everywoman: A New Psychology of Women. New York: Harper & Row. Bolen, J.S. (1989). Gods in Everyman: A New Psychology of Men's Lives and Loves. New York: Harper & Row.

Campbell, J. (1982). The Masks of God: Oriental Mythology Baltimore: Penguin. (Original work published 1962).

Diel, P. (1980). Symbolism in Greek Mythology: Human desire and its transformations. Boulder, CO: Shambhala.

Feinstein, D., & Krippner, S. (1997). The Mythic Path. New York: Putnam/Tarcher. Garun du. (2002, Summer). Dear Gods! Queer Gods! Circle Magazine, p. 11.

Guirand, F. (1968). New Larousse Encyclopedia of Mythology (rev. ed.). London: Hamlyn. Highwater, J. (1990). Myth and Sexuality. New York: New American Library.

Middleton, J. (Ed.). (1967). Myth and Cosmos. Austin: University of Texas Press. Parker, D. (1996). Goddess Power. Carmel, CA: Dynamic Publishers.

Sullivan, L.E. (1988). Icanchu's Drum: An Orientation to South American Mythology. New York: Macmillan.

Shorter versions of this article were published in Proceedings of the 18th International Conference on the Study of Shamanism (pp. 181-188), Ruth-Inge Heinze (Editor), Independent Scholars of Asia, Berkeley, and in the abstract booklet of the 16th World Congress of Sexology, Havana Cuba. Research for this article was supported by the Chair for the Study of Consciousness, Saybrook Graduate School.