Curtis Colliver was a 24-year-old substance abuser when he entered a residential treatment program and began keeping a dream diary. Once he finished the 28-day program, he shared three dreams from his diary with me that took place at approximately weekly intervals:

I get out of prison and run into some people who smoke crack. I buy some and leave it on a table. When I return, a group of men are smoking it. They give it back and I go off looking for a place to smoke.

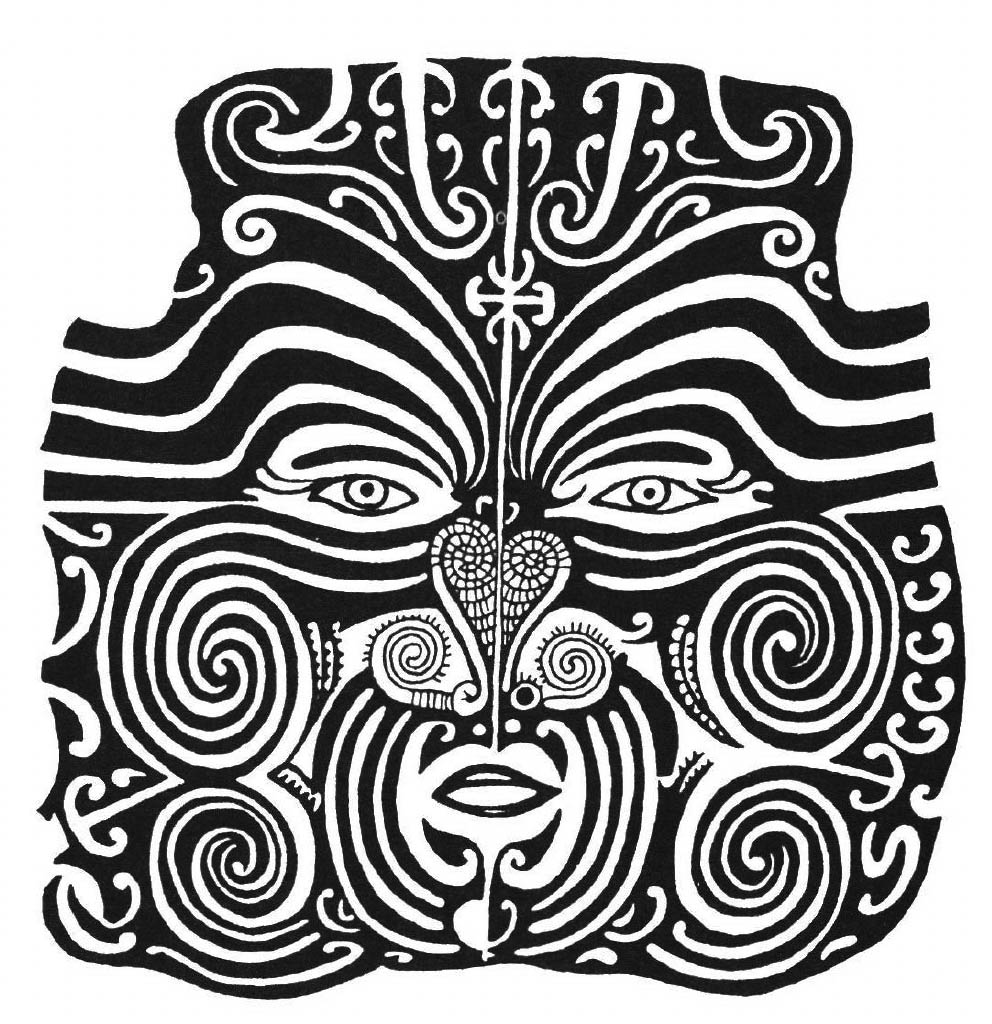

I am in a bus station with two other men. One man is shooting speed. I say that I want some. He gives the other guy a shot first. He pulls the needle out and then puts the rest in my arm. I am thinking that it is going to be way too much and that I will overdose. When he put the needle in, it looked like a hook going into a worm and reminded me of a worn-out vagina eating up a penis. I waited for the taste in my mouth and death—but they never came. I looked at him with surprise and disappointment.

I go into a doghouse and find a gorilla who is a crack dealer. He tries to sell me a block of coke. He breaks off a piece, spilling some on his chest and flicking it onto the floor with his finger. I put some in a pipe and put it to my mouth. I am thinking about losing my sobriety and decide not to smoke.

On one level, the dreams reflect his involvement with crack, speed, and cocaine. At another level, they represent three stages in his personal growth, moving from blatant use in the first dream to concern over the consequences in the second dream, to maintaining sobriety in the third.

In our discussions, Curtis retold the dreams in the following way:

I get out of the treatment center and run into some of my crack-smoking buddies. I buy some but am not sure if I want to relapse so I put it aside. When I come back, a group of crack dealers have started to smoke it. They know that if I see them smoking, they will hook me again. So they give me what is left over and I take off looking for a place to smoke where people from the treatment center won't find me.

My life is in transition, and I am with two speed dealers. One of them is shooting speed. This is an inducement for me to want to use it, but he gives the other guy a shot first, knowing that the dealer will make me want it even more. He pulls the needle out of the other guy's arm and puts the rest of the speed in my arm. I am thinking that I don't have tolerance for it anymore and that I will overdose. When he put the needle in my arm, it looked like he had me hooked on his bait. It also reminded me of the almost sexual comfort I got from drugs, a sexual seduction that should be worn out by now but which is still eating up my vitality and destroying my manly resolve. I waited for the characteristic taste of speed in my mouth and the death I knew was coming. But they never came. I was surprised but also disappointed because "ego-death" – forgetting my identity and therefore, my problems – is one of the drug effects I enjoyed most.

I'm in the doghouse because I'm tempted to use drugs again. The crack dealer is a real animal, and I don't dare turn him down. He tries to sell me a block of crack. He breaks off a piece, spilling some on his chest and flicking it onto the floor with his finger – demonstrating to me that he has an abundant supply, that there's always more where this block came from. I put some crack in a pipe and put it to my mouth. But I realize that I would lose my sobriety so I decide not to smoke. This is the first time I can remember that I ever took responsibility for myself in a dream and am not passive and powerless.

I have found this dreamworking technique to be simple yet useful. The dreamer simply retells the dream as if it were a story about his or her life (Krippner & Dillard, 1988). The dream story can be written or expressed verbally. Sometimes it helps for each story to be given a title. The dreamworker can ask simple questions about the content of the story, e.g., "What emotional feeling did you experience when you decided not to smoke the pipeful of crack?" "What would you do or say if the gorilla tried to force you to smoke the crack?" In addition, the stories can initiate the discussion of crucial issues: the desire for ego death in the second dream could lead to a discourse on what has been called "a caricature of the transcendental state" (Kiley, 1988, p. 15) and a discussion of better ways to fulfill one's spiritual needs.

In the 12 months since completing the treatment program, Curtis has only relapsed three times, once with marijuana, once with cocaine, and once with alcohol. He continues to work with his dreams. One day he told me that he remembered a dream in which he relapsed and felt very depressed because he thought this might presage a relapse in waking life. However, I told Curtis about the Choi study in which 83% of the alcoholics who had been sober for more than one year had dreamed about relapsing at least once, as compared with 37% who had not been abstinent for a year. Although there are several possible interpretations for this finding, the data themselves were reassuring to Curtis. Like the subject in Choi's study, Colliver did not enjoy the drug experience in his dream. In fact, the dream preceded Curtis' current period of complete sobriety.

Author's note: Curtis is still sober. This is quite an accomplishment, given the relapse rate for cocaine addiction. He dreams about addictive drugs from time to time, but the frequency is less.

References:

Choi, S.Y. (1973), Dreams as a prognostic factor in alcoholism. American Journal of Psychiatry, 130, 699-702.

Kiley, L. (1988). Addiction and consciousness: Exploring the relationship. Addiction and Consciousness Journal, 3, 3-4, 15.

Krippner, S., & Dillard, J. (1988). Dreamworking: How to Use Your Dreams for Creative Problem-Solving. Buffalo, NY: Bearly.

This article originally appeared in the ASD Newsletter, Vol. 6, No. 5, Sept/Oct 1989. It is reprinted here with the author's permission and the addition of an author's note.