by Stanley Krippner & Allan Combs

Crick and Mitchison’s 1983 Nature article on REM sleep as a random brain process involved in offline memory consolidation reinforced the view, already held by many psychologists and brain scientists, that dream content is meaningless. For example, Myers (2001) describes dreams as nothing more than hallucinations of the sleeping mind. These authors based their thinking on the idea that the brain is a neural network that stores information during the day, but in which nighttime stochastic noise is needed to cleanse it of unwanted information that would otherwise overload its capacity. At the time this notion was fashionable in the neural network community. But it failed to pan out in actual neural network simulations and current research tends to focus on the opposite problem of how such systems can overcome noise (White, Lee, & Sompolinsky, 2004). Crick and Mitchison pressed this idea so far as to assert that people should not be encouraged to remember their dreams because such attempts at recall may help to retain patterns of thought that “are better forgotten.” Erwin (1985) added, “It might turn out that dream analysis is not only of little clinical value, but is actually harmful.” Contrary to these perspectives, many investigations of dream reports support the conclusion that dream narratives are not unpatterned, but, in Alfred Adler’s (1938) terms, reflect a basic continuity with waking life, a perspective later developed by Calvin Hall (1953), among others. This evidence comes from several sources, i.e., cross-cultural and gender studies, clinical and cognitive psychology data, psychological therapy research, explorations in developmental psychology, and speculations from evolutionary psychology.

Cross-Cultural Studies

A continuity between dreamers’ everyday activities and their dream reports has been shown both for individuals (e.g., Winget, Kramer, & Whitman, 1972; Domhoff, 2001) and for cultures (e.g., D’Andrade, 1990; Prasad, 1982). Consistent with Adler’s view and, incidentally, contrary to Freud’s wishfulfillment hypothesis, an unusually low frequency of food consumption has been reported in dream reports within populations where food is scarce (Monroe, Nerlove, & Daniels, 1969). Levine (1966) studied three groups of male Nigerian students, finding that their dream content differed in relation to their tribal background. For example, the Ibo culture has a value system and social structure favoring upward mobility of its members. The Hausa culture does not support social mobility and individual achievement, while the Yoruba culture takes an intermediate position. The Yoruba students’ dream reports contained more achievement themes than those of Hausa students, but less than those of Ibo students, exactly what one would predict if dream life reflects waking life. In addition, dream reports from small traditional societies display a higher percentage of animal characters when compared with industrialized societies (Van de Castle, 1994).

Gender Differences

There are several similarities between genders; for both men and women, there is usually more aggression than friendliness, more misfortune than good fortune, and more negative emotions than positive emotions (Domhoff, 2001, p. 23). At the same time, gender differences have consistently emerged in the literature (e.g., Domhoff, 1996; Soper, Rosenthal, & Milford, 1994), usually showing a higher incidence of aggression in dreams reported by men than by women, and differences in the ratios of male and female dream characters. However, there are exceptions to these generalizations (e.g., Hobson, 2002, p. 152). In their examination of dream reports from 240 Brazilians, Krippner and Weinhold (2001) observed that both genders reported about the same proportion of male dream characters; nor were there gender differences in regard to aggressive interactions. However, significantly more children appeared in the dream reports of Brazilian women than of Brazilian men; friendly interactions and food references were more frequent in female dream reports as well.

Clinical Psychology

Several studies from the field of clinical psychology indicate that people undergoing episodes of clinical depression report more dreams set in the past than do non-depressed people. Further, depressed dreamers report more content characterized by masochism, dependency, and blandness of affect. If the depression begins to lift, however, the dream content changes, with more feeling and emotion appearing in the dream reports (Cartwright, 1986). Nightmares, those dreams with terrifying content that frighten the dreamer and can be recalled upon awakening, peak in childhood. Among adults, they can often be traced back to stressful events in the dreamer’s life (Kothe & Pietrowsky, 2001), especially in people afflicted by post-traumatic stress disorders (Ursano, 2002). In addition, they have been found to be associated with such personality variables as anxiety, depression, somatization, and “thin boundaries” (e.g., Hartmann, 1998). These links between dream life and waking life present some of the most formidable evidence that dream reports reflect patterning and meaning; the occurrence of nightmares in children may be one of several examples of interactions between brain development and socialization.

Cognitive Psychology

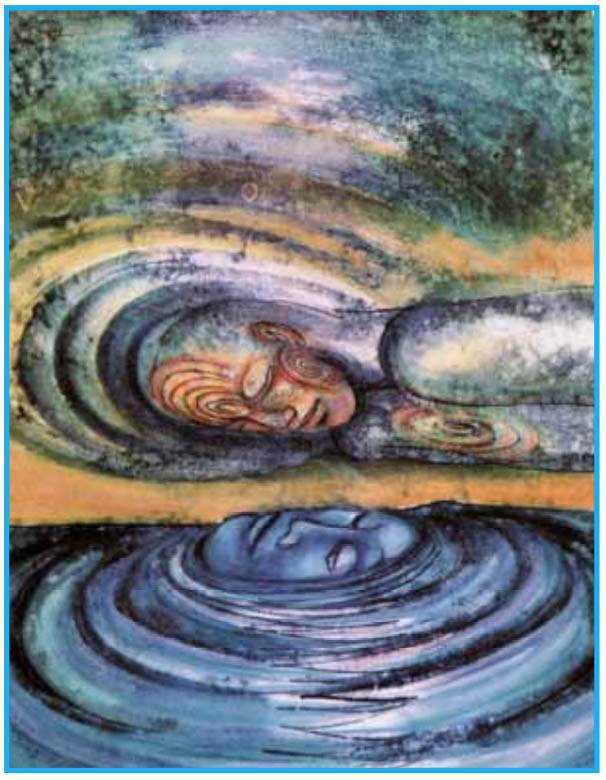

There are considerable data indicating that the areas of the brain most active in dreaming are those associated with visual and motor activity, imagery, emotion, and metaphorical thinking. Ancient sleep temples and such practices as dream incubation were early attempts to use dreaming for problem-solving. More recently, dreams have been linked to oncoming medical problems and, in some cases, their resolution (Kasatkin, 1967; Smith, 1990). Barrett (2001) described dreaming as “the mind thinking in a different biochemical mode” (p. 184) and presented dozens of instances of novelty, creativity, and invention in dream reports. Her survey indicated that visual and narrative ideas are more compatible with dreaming, while logic, music, and mathematics are less common. One is reminded of many well documented incidences such as Friedrich Kekule’s discovery of the benzene ring while in a semidreaming state (Ghiselin, 1955).

Robert Louis Stevenson described dream “brownies” that helped him “to build the scene of a considerate story and to arrange emotions in progressive order” (p. 64). He gave as an example the role of dreaming in the production of his 1886 novella The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, which occurred sequentially during several dreams. Domhoff (1996) wrote that the use of content analysis to study dream reports has demonstrated a “consistency in what individuals dream about from year to year and even over decades,” as well as “correspondences between dream content and waking life” and “a direct continuity between dream concerns and waking concerns” (p. 1). These conclusions argue against the notion that dreams lack pattern and meaning.

Psychological Therapy

Dream work is not an essential practice in psychological therapy. However, there is a body of evidence that it enhances clients’ satisfaction with the psychotherapeutic process and that it increases clients’ insights, especially regarding the connections between dream life and waking life. Modest positive changes have been noted in the clients’ interpersonal functioning and reduced symptomatology (Hill & Goates, 2004). Most of this research has utilized Hill’s (1996) three-stage cognitive-experiential dream model consisting of exploration, insight, and action. In addition, several descriptive articles have attested to the effectiveness of Ullman’s (1994, 1996) experiential group dream process (e.g., Krippner, Gabel, Green, & Rubien, 1994; Ullman & Limmer, 1987).

Developmental Psychology

The continuity between dream life and waking life is evident in the parallel between dream reports and waking thought, a similarity overlooked by many theorists but supported by considerable comparative data (Domhoff, 2001, p. 19). This parallel extends to developmental studies; longitudinal research involving children’s dream reports demonstrates increases in narrative complexity as children mature (Foulkes, 1999). Children’s dream reports contain content markedly different than that found in adult reports. For children under age 5, reports consist primarily of bland and static images, typically of eating, drinking, or animal figures. Children between the ages of 4 and 8 report nightmares more frequently than any other age group, and these reports decline with age (McNamara, 2004, p. 136). During this same time period, there is an increase in interpersonal interactions but without the high levels of aggression, misfortune, and unpleasant emotions found in adult dream reports (Foulkes, 1999). Gender differences begin to appear in late childhood and become more prevalent in adolescence. In other words, dreaming appears to be a cognitive achievement that develops gradually, as do other cognitive skills (Domhoff, 2001, p. 20). This developmental sequence runs counter to the assumption that dream content is random and unpatterned.

Evolutionary Psychology

Ullman (2001) has reminded us that “as members of the mammalian evolutionary line we share two forms of consciousness with our fellow creatures, namely, waking consciousness and the distinctly different form of dreaming consciousness that surfaces periodically during sleep” (p. 1). Revonsuo (2000), having noted the high proportion of dream reports containing negative affect, proposed that these are a carry-over from primordial eras when waking life was more dangerous. Revonsuo suggested that dreams represent a genetically transmitted predisposition for survival scenarios retained and rehearsed during sleep for waking applications. Hence, dreams are not only patterned and meaningful, but adaptive as well.

McNamara (2004) has presented a contrasting view that also draws upon evolutionary psychology. For Mc- Namara, dreams are the creative product of an adaptive process that is crucial to the development of authentic human communication and “hard-to-fake” emotions, as well as human culture in general. During this process, REM (rapid eye movement) and non-REM sleep are often antagonistic, yet dreaming can occur in either. McNamara deconstructs many orthodox perspectives, most notably the notion that dream content is a meaningless chance occurrence. To the contrary, many dreams are accompanied by “costly signals” such as rapid eye movements and indications of distress (which is why there are so many unpleasant reported dreams). The dreaming primate’s mother pays special attention to those infants whose behaviors are signs of the most distress, thus perpetuating the genes responsible for these “signals.” McNamara concludes that, rather than being artifacts of nighttime sleep, dreams are “central to human behavior, well-being, and culture” (p. 166).

Patterns and Meaning, or Sound and Fury?

Hobson and McCarley’s influential publication of the activation-synthesis hypothesis in 1977, argued that dream experiences are efforts of the optic cortex to make sense of un-patterned stimulation of the visual-motor cortex, primarily during REM sleep. The “synthesis” aspect of this model refers to the brain’s efforts to produce a coherent sequence of images and events out of these inputs. From our perspective, Hobson sees the “patterning” as following the “activation” process; “meaning” is attributed to this “pattern” during wakefulness. Since then Hobson and his colleagues have continued to enlarge and develop their theory, describing how the brain “not only self-activates and isolates itself from the world, but it changes its chemical climate very radically” (p. 162), processing the sensorimotor and emotional data that comprise a dream, often evoking hallucinatory experiences that may exhibit a “surreal intensity that would have pleased Andre’ Breton as much as Leonardo da Vinci” (Hobson, 2002, p. 25). Because dream content is “highly individual,” dreams “can still find a place in personal psychology and psychotherapy” (p. 151), even though it does not reflect disguised wishes and drives (p. 158).

Does the patterning take place before or after the dreamer awakes? This review strongly indicates that dream reports are both patterned and meaningful. However, Hall (1981) conjectured that this patterning took place as the dreamer emerged from sleep and Domhoff (1999; 2001, p. 22) is among those who have suggested that the attribution of meaning to a dream occurs after a dream occurs, not during its production. Cartwright (2000) makes a valid point when she calls for “a breakthrough in technology” to illuminate what is happening in the brain during dreaming, as well as “more sensitive inquiry of observers and patients to describe this experience” (p. 915).

A Shakespearean character poetically dismissed dreams as experiences “filled with sound and fury, signifying nothing.” This statement served a dramatic purpose in Romeo and Juliet, but portrays a point of view that is not consistent with 21st century dream science. Indeed, Hobson (2002) has described the scientific study of dreaming as “a true renaissance, a genuine revolution…[that] can be seen as a crucial part of a larger project, one that will shake the foundations of philosophy, psychology, and psychiatry” (pp. 160-161). This visionary declaration is one that can motivate both scientists and practitioners, both laboratory and field researchers, both writers driven by theory and those bound by data. The only folks left behind are those who, in the face of evidence from multiple disciplines, still cling to the notion that dream reports “signify nothing.” ℘

References

Adler, A. (1938). Social interest: Challenge to mankind. London: Faber and Faber.

Barrett, D. (2001). The Committee of Sleep. New York: Crown.

Cartwright, R. (1986). Affect and dream work from an information processing point of view. Journal of Mind and Behavior, 7, 411-428.

Cartwright, R. (2000). How and why the brain makes dreams: A report card on current research on dreaming. Behavior and Brain Sciences, 23, 914-916.

Crick, F., & Mitchison, G. (1983). The function of dream sleep. Nature, 304, 111-114.

D’Andrade, R.G. (1990). Some propositions about the relations between cultural and human cognition. In J.W. Stigler, R.A. Shweder, & G. Herdt (Eds.), Cultural psychology: Essays on comparative human development (pp. 65-129). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Domhoff, G.W. (1996). Finding meaning in dreams: A quantitative approach. New York: Plenum.

Domhoff, G.W. (1999). Drawing theoretical implications from descriptive empirical findings on dream content. Dreaming, 9, 201-210.

Domhoff, G.W. (2001). A new neurocognitive theory of dreams. Dreaming, 11, 13-33.

Erwin, E. (1985). Holistic psychotherapies: What works? In D. Stalker & C. Glymour (Eds.), Examining holistic medicine (pp. 245-272). Buffalo, NY: Prometheus Books.

Foulkes, D. (1999). Children’s dreaming and the development of consciousness. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Ghiselin, B. (1955). The creative process: A symposium. New York: New American Library.

Hall, C.S. (1953). A cognitive theory of dream symbols. Journal of General Psychology, 49, 273-282.

Hall, C.S. (1981). Do we dream during sleep? Evidence for the Goblot hypothesis. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 53, 239-246.

Hartmann, E. (1998). Dreams and nightmares: The new theory on the origin and meaning of dreams. New York: Plenum.

Hill, C.E. (1996). Working with dreams in psychotherapy. New York: Guilford Press.

Hill, C.E., & Goates, M.K. (2004). Research on the Hill cognitive-experiential dream model. In C.E. Hill (Ed.), Dream work in therapy: Facilitating exploration, insight, and action. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Hobson, J.A. (2002). Dreaming: An introduction to the science of sleep. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Hobson, J.A., & McCarley, R. (1977). The brain as a dream state generator: An activation-synthesis hypothesis of the dream process. American Journal of Psychiatry, 134, 1335-1348.

Kasatkin, V. (1967). Theory of dreams. Leningrad: Meditsina.

Krippner, S., Gabel, S., Green, J., & Rubien, R. (1994). Community applications of an experiential group approach to teaching dreamwork. Dreaming, 4, 215-222.

Krippner, S., & Weinhold, J. (2001). Gender differences in the content analysis of 240 dream reports from Brazilian participants in dream seminars. Dreaming, 11, 35-42.

Levine, R. (1966). Dreams and deeds: Achievement motivation in Nigeria. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

McNamara, P. (2004). An evolutionary psychology of sleep and dreams. Westport, CT: Praeger.

Monroe, R., Nerlove, S., & Daniels, R. (1969). Effects of population density on food concerns in three East Africa societies. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 10, 111-114.

Myers, D.G. (2001). Psychology. New York: Worth.

Prasad, B. (1982). Content analysis of dreams of Indian and American college students – a cultural comparison. Journal of Indian Psychology, 4, 54-64.

Revonsuo, A. (2000). The reinterpretation of dreams: An evolutionary hypothesis of the function of dreaming. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 23, 877-901.

Smith, R.C. (1990). Traumatic dreams as an early warning of health problems. In S. Krippner (Ed.), Dreamtime and dreamwork: Decoding the language of the night (pp. 224-232). Los Angeles: Jeremy P. Tarcher/Perigee.

Soper, B., Rosenthal, G., & Milford, G. (1994). Gender differences in dream perspectives. Psychological Reports, 74, 311-314.

Ullman, M. (1994). The experiential dream group: Its application in the training of therapists. Dreaming, 4, 223-230.

Ullman, M. (1996). Appreciating dreams. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Ullman, M. (2001). A note on the social referents of dreams. Dreaming, 11, 1-12.

Ullman, M., & Limmer, C. (1987). The varieties of dream experience. New York: Continuum.

Ursano, R.J. (2002). Post-traumatic stress disorder. New England Journal of Medicine, 346, 130-132.

Van de Castle, R.L. (1994). Our dreaming mind. New York: Ballantine.

White, O.L., Lee, D.D., & Sompolinsky, H. (2004). Short-term memory in orthogonal neural networks. Physical Review Letters, 92, 148102-1-148102-4.

Winget, C., Kramer, M., & Whitman, R.M. (1972). Dreams and demography. Canadian Psychiatric Association Journal, 17, 203-208.

The preparation of this paper was supported by the Chair for the Study of Consciousness, Saybrook Graduate School and Research Center, San Francisco, California. It was presented at “Toward a Science of Consciousness 2006,” April 4-8, Tucson Convention Center, Tucson, Arizona.