This is the ninth in a series of excerpts from an ongoing dialogue between Russell Lockhart and Paco Mitchell.

Queries & Speculations Twenty-Three: Eros and Thanatos

Paco Mitchell: Russ, we’ve had many conversations about the contemporary and the upcoming world-situations, and we’re no strangers to its more “dour” aspects. You have the excuse of being a fully-fledged Scot, and therefore can claim to be “dour by nature”, though you also claim to be “optimistic by nature” at the same time—an apparent conflict. My guess is that this is simply human ambivalence, which expresses itself at the most basic levels, all the way down to the mystery of X and Y chromosomes during fertilization, for example, or perhaps the fact that homo sapiens is deeply rooted in the reptilian brain—wisdom growing from the serpent. On the other hand, I can only claim partial Scottish dourness, due to the mixed bloodlines in my family. Therefore, I will claim the remainder of my own dourness as deriving from a genetic Bohemian off-shoot which, fancifully, may account for my passionate involvement in Gypsy flamenco and the cante jondo. But that’s another story.

All this is a half-whimsical introduction to the extremely powerful impact your reply to Q & S Twenty-Two had on me. We have been working our slow, sinuous, reptilian way for some time now, and I can’t help but feel that we are standing at the brink of something that is practically beyond words. In fact, between our last exchange and this one, I happened to re-read your book Psyche Speaks, and I found you saying much the same thing, about the still-living possibility of a nuclear holocaust. In other words, it produced a sadness in you that virtually left you speechless.

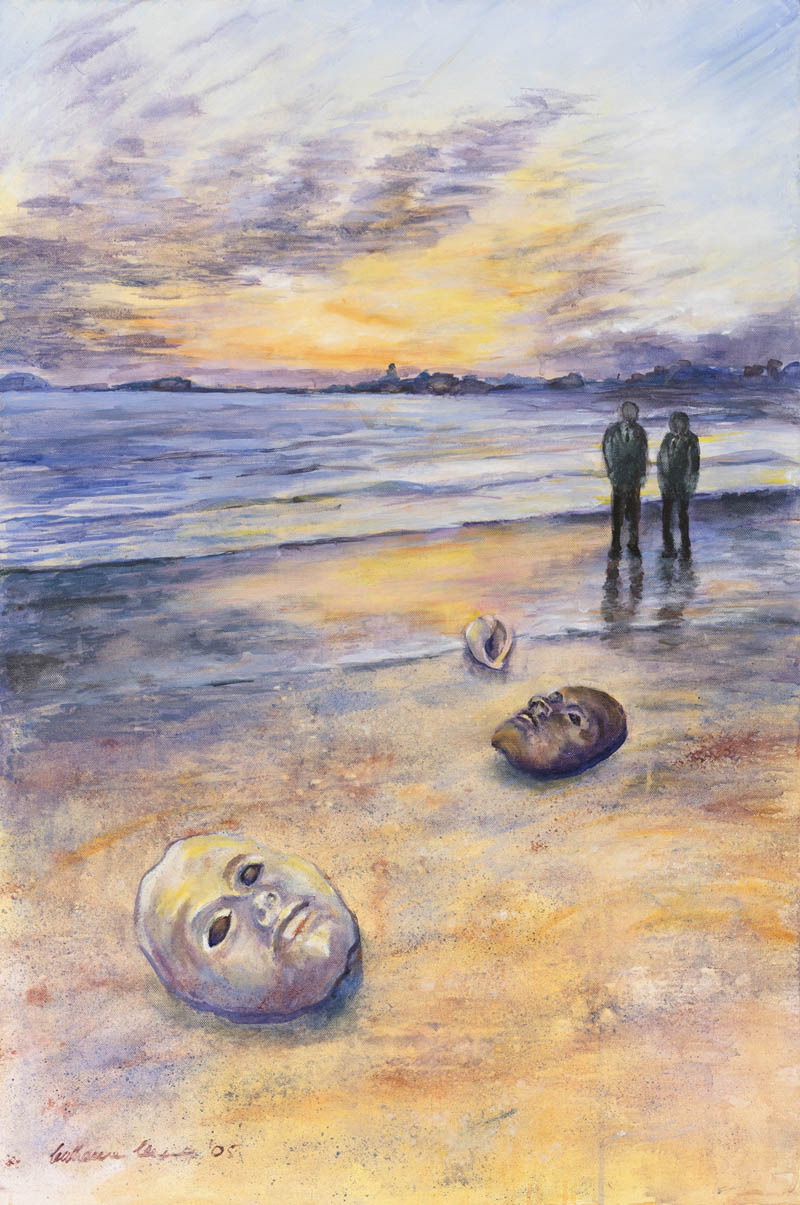

I feel much the same way. Considering everything you noted in your reply to Q & S Twenty-Two there seem to be no real “solutions” to the accelerating consequences of the global climate dilemma, solutions so many people expect others to find and carry out for them. Most of the proposed solutions will simply perpetuate what got us into this situation in the first place. Thus, we are approaching what you rightly see as an extremity that will quite possibly activate an enantiodromia of colossal proportions. It will take something supremely huge to shock us out of our slumber—something profoundly different from what we are comfortable with. And even then, as you say, it may not be enough to enable us to alter course in time. Recently, I had a brief conversation with a stranger in a coffee shop. Complementing him on his rakish tweed driver’s cap, we quickly lapsed into one of those “forbidden” climate conversations. Before I knew it, he was using the “E” word (extinction). But he could only follow it up with the notion of giving up, which he repeated over and over. In other words, it seemed that when he contemplated the possibility of human extinction, all he could see was “giving up”. Curiously, I don’t hear you doing that, or myself, or any of the avowed “collapse-niks”, as they humorously call themselves at times, who are devoted to this topic. Everyone I am aware of—the writers who take these dire and dour possibilities to the most extreme points imaginable—end up affirming some form of Eros, or love, or kindness, or generosity, even if it portends or accompanies the end of life. I found it remarkable that in your profound book Psyche Speaks, that’s where you ended up: the threads that ultimately lead us to death, also lead us to what may be the most profound human force of all: Eros. My Q & S Twenty-Three, then, is: What do you think of this?

Russell Lockhart: In Freud’s seminal paper, “The Ego and the Id”, published in 1923, he distinguished between two instincts: the death instinct, “the task of which is to lead organic matter back to the inorganic state”, and Eros which “aims at more far-reaching coalescence of the particles into which living matter has been dispersed”. Earlier, Wilhelm Stekel had called the “death wish” by the name Thanatos. Freud never used this term for the death instinct because of his dislike of Stekel. Freud continued to develop his conception of this duality between Eros and the death instinct, to the point where he wrote in Civilization and Its Discontents in 1930: “The fateful question of the human species seems to me to be whether and to what extent the cultural process developed in it will succeed in mastering the derangements of communal life by the human instinct of aggression and self-destruction… Men have brought their powers of subduing the forces of nature to such a pitch that by using them they could now very easily exterminate one another to the last man”. Freud here suggests that the combination of the death instinct and human ingenuity could lead to the extermination of the human species. This was before the possibility of nuclear extermination and before any apprehension about the ability of the planet to sustain human life given man’s destructive effect on the environment and other life forms.

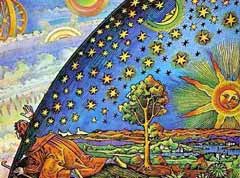

This raises a question. The “return to inorganic matter” is the fate of each one of us individually. This is a biological given and each of us must come to terms with our life’s end in our own way. But can it be that the species itself harbors a “death wish” for the species as a whole? Would that be the final Ragnarök? This idea has more “explanatory” power than we might wish to acknowledge. Freud concludes his essay with this extraordinary statement: “And now it may be expected that the other of the two heavenly forces, eternal Eros, will put forth his strength so as to maintain itself alongside of his equally immortal adversary”. It is fascinating that Freud here raises Eros and Thanatos—previously referred to as human instincts—to heavenly forces (Freud’s emphasis). Freud here is speaking of Eros as an immortal force beyond the human which will be putting forth his strength to “maintain itself” against Thanatos, its immortal adversary. What is it that led Freud to expect Eros to exert itself in this way? Whatever it was, something else happened to Freud, which led him two years later to write in his New Introductory Lectures on Psycho-Analysis:

“…our best hope for the future is that the intellect—the scientific spirit, reason—should in time establish a dictatorship over the human mind. Whatever…opposes such a development is a danger for the future of mankind.”

As I wrote in Psyche Speaks, when first commenting on Freud’s conclusions: “Here Freud seems to forget his call to Eros and falls into the typical stance of siding with reason against the soul. I feel that Freud’s earlier stance was more correct, that the battle is not between Eros and Logos, but between Eros and Thanatos. Thanatos seems ever present in today’s world. But where is Eros? If anything, the world has grown darker since I wrote those words thirty-six years ago, and Eros seems even less visible and present. Psyche Speaks was my effort to point to Eros as what is needed. Jung called this a “great dream”. Jung said that this great dream has always spoken through the artist as “mouthpiece” proclaiming the arrival of the coming guest. It is the artist’s love and passion (the human eros) that needs to be listened to in order to proclaim and welcome the coming guest (the heavenly Eros). In my view, it was the artist in each of us that would be the source of what was necessary to welcome the coming guest. But we seem far from such a realization and manifestation. The earlier Freud expects the arrival of the heavenly Eros. The later Jung expects the arrival of the coming guest. I think both great men are talking about the same thing. Thus, in the face of the final Ragnarök, which seems ever more certain, one may either give up in despair, entertain oneself to death, or manifest ever more fully the human Eros that is love and passion and generative creativity. One must perhaps, celebrate both the final Ragnarök and welcome Eros, the coming guest.

Queries & Speculations Twenty-Four: Freud’s Religion

PM: Russ, your reply to my Q & S Twenty-Three was superb and fascinating. As usual, however, I did get caught up in some tangential questions about some of Freud’s language and epistemological assumptions—in use for over a century and taken for granted by many. I’m referring mainly to the terms “death-instinct” and “death-wish”. The questions I have about their early uses leave me wondering what to think about their altered use by the “1930 Freud”. Maybe you can help. First, I don’t pretend to be a Freudian, if only because of my resistance to reductive materialism generally and reductive dream interpretations. But, despite the ambiguity of the terms instinct and wish, both of which overwhelmingly lend themselves to life-processes, the gist of Freud’s “death-instinct” and “death-wish” seems to reside in the Second Law of Thermodynamics, and its concept of the entropic running down of everything, in what many physicists seem to take pleasure—even a certain glee—in calling the “heat-death of the universe”. This “law” may be as close as we get in modern science to a religious absolutism. Absolute materialism, with no room for the psyche per se, as far as I can see.

So far, then, Freud lines up on one side with the reductive materialists, and Jung, more tolerant of mystery, lines up on the other, on the side of teleological psychologists, let’s call them. But then we arrive at Freud’s unusual reference to the two “heavenly forces”—“eternal Eros” and “his equally immortal adversary (the death-wish, aka ‘Thanatos’)”. Unless I’m missing something, this is anything but the reductive, materialistic Freudian language we’re accustomed to. In fact, one could avail oneself of these same kinds of terms in referring to the archetypal nature of Jung’s collective unconscious. It is certainly not language one would find being bandied about at a Thermodynamics Physics Conference. It’s as if Freud came around over the years and slipped a few non-materialistic “zingers” into his text. So, Russ, after all those decades of Freud’s obeisance to what I’m calling the “absolutism of Thermodynamics”, do you think he was freeing himself from the noose a bit—maybe even from his theory—and opening to his original supporter, then his adversary and failed Crown Prince—Jung? How do you understand this text of the “mystical Freud”?

RL: Freud did refer to Jung as his “successor and crown prince”. This metaphoric phrase, which is based on images of monarchy, places Freud as King and Jung as Crown Prince. This is understood without any complications—psychoanalysis as kingdom. But when Freud says that Jung is his “Joshua to his Moses”, then we have Freud as Moses and Jung as Joshua—another kingdom, but now a religious one. Joshua was Moses’ assistant and he became leader of the Israelites after the death of Moses. But why would a devout atheist and devoted materialist such as Freud use this religious imagery—even metaphorically? Even more puzzling is Freud’s reference to Jung as “the spirit of my spirit”. When Freud made these references to Jung, the depth of connection between the two men is obvious. By 1907, Freud had suffered disappointment after disappointment in seeking someone to carry on his work and bring him and his psychoanalytic kingdom the international recognition that was his passion and his dream (in the “aspirational” sense). In a similar vein, Jung had suffered many disappointments in finding a true mentor, one might say, a deep and powerful father.

In 1907, they found each other, and the possibility of each other’s needs being met, in their first personal meeting, a meeting lasting 13 hours. Others have pointed out how Freud transferred his “homoerotic” connection from Wilhelm Fliess to Jung. From their first encounter, Jung, though fully enamored, was troubled by Freud’s utter rejection of Jung’s invoking the paranormal dimension to explain the knife shattering during their encounter. Others have pointed out as well, Jung’s lifelong trouble in relationships with men. Later, Freud would accuse Jung of harboring a death wish for Freud.

Despite its promise of fulfilling each other’s deep needs, the Freud-Jung relationship was ill-fated from the beginning. I think this mutual regard followed by the complete break between the two men (1913), set the stage for historical crosscurrents still at work today. Freud wrote in his final personal letter to Jung, that Jung had remarked at the 1912 Munich conference, that an intimate relationship with a man inhibited his scientific freedom. By breaking off their intimate relation, Freud told Jung to take his full freedom and to forego any “tokens of friendship”. Freud had asked Jung not to abandon the sexual theory, but to make a dogma of it, an “unshakable bulwark” against the “black tide of mud of occultism”. Jung later characterized this as unscientific and a clear example of Freud’s “personal power drive”. But more importantly, Jung described this as “an indisputable confession of faith”, whose only aim was “to suppress doubt”. Here, it seems to me, Jung is responding to Freud’s religion: Jung was not a good Joshua to Freud’s adamantine Moses. And Freud’s religion? Since Freud said he had no religion, was an avowed atheist and a profound materialist, why refer to his religion? I think there are grounds for a different view than the usual one and I’ll try to weave various threads together for a coherent sense of what I mean, keeping in mind I am trying to elucidate inchoate intuitions.

Freud, in one trip to Rome, had placed himself in front of Michelangelo’s Moses every day for thirteen days. What was Freud doing? We can say he was identifying with Moses. But in what sense? What is the ground of the connection between Moses and Freud? Freud’s last major work, Moses and Monotheism published in 1939, caused Freud such difficulty, that he finally referred to it as his “fiction”. In this work, Freud claimed that Moses was not Hebrew, but born into Egyptian nobility. Freud conjectured that Moses was a follower of Akhenaten, an ancient monotheist ruler. Freud speculated that it was the murder of Moses by his followers that led to collective guilt that induced the hoped-for return of Moses as the Messiah. The Jewish religion, Freud said, was developed to alleviate this guilt. Freud died a few months after the publication of Moses and Monotheism. In this late “fiction”, Freud rationally constructs his “explanation” of the Jewish religion, while not observing how these very same factors played such a part—or metaphorically—in his own psychoanalytic kingdom, its followers, and its heretics. Is it possible that what this fiction reveals are Freud’s own deep religious currents, perhaps ghosts of his father’s Hasidism and accomplishments in the study of Torah? Critics have latched onto this and said that Freud’s audacious claims were, indeed, “pure fiction”. Perhaps it is in Freud’s fictions that his “underground” religious nature is most revealed.

Freud was identifying with Moses, not as the figure of the Hebrew religion, but with Moses as the murdered monotheist Egyptian. So, what is it that this “fiction” is picturing? In 1907, Freud was asked to produce a list of “ten good books”. On Freud’s list was Dimitry Seregeyevich Merezhovsky’s Leonardo da Vinci: A Biographical Novel from the Turn of the Fifteenth Century, published in 1902, and read by Freud in German translation in 1903. This book was the second volume of a trilogy referred to as “Christ and Anti-Christ”. The first volume was entitled The Death of the Gods. The third volume was entitled Peter and Alexis. Merezhovsky is no longer well known or read, but in Freud’s day, he was a major literary figure in Russia and in Europe. He was nominated for the Nobel Prize in literature ten times. He founded the symbolist movement in Russia. He was seen as continuing the legacy of Turgenev, Tolstoy and Dostoevsky. His poetry was set to music by Rachmaninoff and Tchaikovsky. He and his wife (a major poet) were the most prolific literary couple in Russian history. And, of most relevance to our present context, he founded the religious movement known as “The Third Testament”.

The first symbolist novel, The Death of the Gods: Julian the Apostate, focused on Emperor Julian, who tried to reinstate the Olympian Gods after the triumph of Christian monotheism. In the novel, Christianity is pictured as a cult that denies the body and where redemption cannot be attained on earth. Merezhovsky pictured this denial as denial of reality. In the novel, Christians treat Julian as the Antichrist. In this and the rest of the trilogy, Merezhovsky argues that the highest level of human development is the uniting of spirit and body on earth. For these views, Merezhovsky was persecuted by the Russian Church and the Russian authorities, his books banned and burned. Shortly after the turn of the century, Merezhovsky and his wife formed a group called, “Religious-Philosophical Meetings”, devoted to perfecting the union of spirit and body. After a short time, the meetings were declared illegal by the Russian Orthodox Church, but were revived again in 1907, when Merezhovsky began promulgating the idea of the Kingdom to come under the advent of the Holy Ghost.

Merezhovsky revived Joachim of Fiore’s twelfth-century doctrine of the “Third Kingdom”, which was to be the Kingdom, not of God, not of the Son, but of the Holy Ghost. Merezhovsky saw such a time as the union of all previous polar opposites (e.g., body and spirit, male and female, rational and irrational, etc.), and manifest on earth. In this he saw art playing a crucial role in this evolution of what humans could become. This is the Third Testament that Merezhovsky proposed. He foresaw that this evolution would be preceded by catastrophes, not the least of which would be necessary revolutions and rebellions in the state, in institutions, in religions, essentially in all structures. Needless to say, his ideas were seen as scandalous and heretical, just as scandalous and heretical as did Freud’s ideas which followed. His books and prophecies have been, in the words of one commentator, “aggressively forgotten”, until the past decade, where his work is now receiving serious attention.

So, after this excursus, how does the work of Merezhovsky relate to your question about Freud’s eternal heavenly Eros? It does appear that Freud stepped out of his Moses self in talking about Eros and the death instinct (Thanatos) in 1930, before he fell back into “the laws” promulgated in 1932. AE’s “Pilgrim of Eternity”, Merezhovsky’s “Holy Ghost”, “Freud’s “Eternal Eros”, Jung’s “Coming Guest”, all point to some future time when life on earth will be changed from anything humans have ever known. Life on earth transformed. All these conceptions were intuited in the declining years of the Piscean age. All are perhaps intuitive pictures of life on earth in the coming Aquarian age. They all in one way or another embody the idea of union of opposites.