This is the third in a series of excerpts from an ongoing dialogue between Russell Lockhart and Paco Mitchell.

Paco Mitchell: Russ, at the beginning of our Dialogue #2 you said: “But, at bottom, we are all linked by a kind of rhizome layer.” That’s a huge statement. For centuries we’ve labored under the opposite assumption, that we’re not all linked, that we’re separate, that the universe is a machine, even that we are machines. We’ve devoted ourselves to the principle that knowledge is served by slicing everything into finer and finer discrete pieces—we know more and more about less and less. But with a knowledge of the parts came control over the whole—or so we thought. We were bound to become... Masters of the Universe!

But now you speak of another level of knowing that has escaped the attention of our restless blade, like a baby in the bulrushes, hidden from Herod’s soldiers. This “rhizome layer” is some kind of unitary phenomenon that underlies consciousness. I’ve been thinking of it, provisionally, in terms of “continuous time,” as a way to contrast it from the “discontinuous time” that goes with our Western mind-set.

Current modes of thought scarcely admit the existence of your “rhizome,” even though it amounts to one of the most primordial of experiences. We need a different means of approach that will enable us to see into the darkness of what, in former ages, was common knowledge. This would amount to a new way of knowing... but one that is also very old.

In his book The Dream of the Earth, Thomas Berry evokes the “shamanic personality” as something we urgently need to cultivate, now and in the future. To do this we must recover an old way of seeing imaginatively, but in the light of present knowledge. I understand the shamanic personality as a certain disposition—imaginative, poetic, alert to dreams and synchronicities, capable of discerning the patterns that emerge from both waking and dreaming experience. In short, a disposition to recognize the “imaginal realm”—Henri Corbin’s mundus imaginalis—as real. The shamanic personality, it would seem, is well-suited to healing the rift between the continuous time of the rhizomic layer, and the discontinuous time of modern consciousness.

Of course, we need to re-educate ourselves in those imaginative ways, which are so legion as to constitute a virtual labyrinth! How do you orient yourself in the face of these possibilities and how would you suggest others orient themselves?

Russell Lockhart: This labyrinth of possibilities is a core image, to be sure, and captures well the problem set before us. I want to say, first, that I do not think “orienting” can be codified, no matter how intense the effort. Think of Daedalus and his son Icarus in the labyrinth. So, following myth, we have the Icarian grand schemes whose promise always seems to melt away and crash; or, the Daedalian inventiveness that raises us just enough and over the edge to freedom, but generally freedom only to go on about what was before.

I remember now that my father-in-law wrote a poem, “In A Labyrinth,” in which—in contrast to the myth— something different happened: “I saw a tiniest crevice—see?” Well, an entirely different story unfolds from that, does it not? Thus, I see that an orientation to the “labyrinth of imaginative possibilities” is itself highly individual.

For myself, I pay most attention to what “presents” itself. Just now, for example, the memory of something I read in John Fowles’ essay, The Tree, presented itself in my experience. Does it belong here? I don’t know that it does, yet I trust that it does. Fowles first described standing in the world’s most perfect garden, at least since the Garden of Eden. It was Carl Linnaeus’ garden, the embodiment of the spirit of Linnaeus’ “ordering of nature,” which to this day, determines so much not only how we “see” order in nature, but as well how we try to “order” the nature of our lives. Fowles declared himself a Linnaean heretic and even reveled in the fact that Linnaeus, at the end of his life, had gone completely mad.

Fowles then goes on to describe an experience of his childhood. An elderly man in his neighborhood had gone mad upon the death of his wife and simply withdrew from the world. What had been an orderly landscape turned to seed and weeds took over; all manner of “undesirable elements” took hold. It became a complete eyesore, blighting the neighborhood, the very antithesis of that for which we strive. Yet, into this complete horror, as Fowles walked by one day, landed Britain’s rarest bird, a waxwing, nibbling happily on a crop of wild berries. How does one prepare for that?

I know only that most of the time we are preparing distractedly against it and this is terribly costly to our soul and our spirit. So, this response to your question is itself an example of how I orient myself.

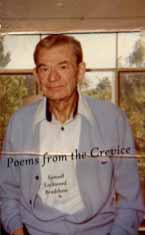

And... here’s something more. When I remembered that image from my father-in-law’s poem, I knew I had the title of the book I want to publish of his poems: Poems from the Crevice. Then, I asked my wife to find me a picture of him to use on the cover, and she gave me a small photograph that had been folded and so had an “imperfection” running across it. There was the crevice! The cover designed itself in my imagination and I sat right down and laid it out— as you can see in the accompanying picture.

PM: So, you orient yourself to imaginative possibilities by paying attention to accidents, imperfections and the unexpected—“gifts of the imagination,” we might say... threads that lead us further into the labyrinth, not out of it.

This suggests an artistic sensibility. A poet, for example, catches aleatory images, like butterflies in a net, dresses them up in words and borrows them to craft a poem. A scientist reading a numerical printout scans for anomalies in the “data”— that which is given—and from those unexpected patterns develops a theory. Your trust in the face of not-knowing is a bit unusual. Not everybody is as comfortable with uncertainty as you. You see opportunities in chance events—openings to another level of reality. And it is not directed consciousness that you apply to the initiatory event but a deeper sensitivity, perhaps even an “animal knowing.” Something about the moment fits an unconscious pattern. And something in you—in us— recognizes it.

I think of that something as a “subliminal knowing witness.” And you have learned, by experience and inclination, to trust, to listen to, this subtle witness. Who or what is the knowing witness? We can say, “Oh, that’s just intuition at work.” Fair enough. But I suspect there’s more to it than that. Something closer to an imaginal person, a “who” more than a “what”—whether the person be animal, human or both. From within the shadowy penumbra of our consciousness, this “something” directs our attention toward the scintillae sparkling there—a topic we might take up elsewhere.

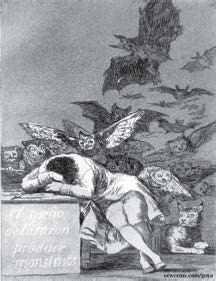

You mention John Fowles’ story about how Linnaeus, after a lifetime of obsessively and devoutly classifying nature, went mad. It reminds me of Goya’s etching “The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters.”

Perhaps if Linnaeus had listened to Goya’s owls, or had paid more attention to the “tiniest crevice” your father-in-law wrote about, Linnaeus might not have ended his life in madness. As it was, he exemplified the scientific spirit of his time, and he paid a price for the inherent imbalance within that spirit, the fantasy of rational control over nature. Goya’s etchings—Los Caprichos or the “The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters” Goya “whims”—illustrated some of the dangers of that imbalance. And we’re still paying the price today. But your approach elevates hidden nuances and overlooked subtleties. How? By allowing your attention and interest—your libido to be deflected toward the background of consciousness? Let’s call that a kind of “liminal vision”—seeing into the dark—and recognize that it leads us toward the rhizome layer. The imaginal realm. The creative unconscious. The dream. So when you say you orient yourself to the imagination with whatever “presents” itself, you often start with what is small, negligible. But as you follow the trail of hints, you are led to larger and larger patterns, which together begin to reveal the rhizome. This is as much a way of working with dreams as of composing books, or writing poems.

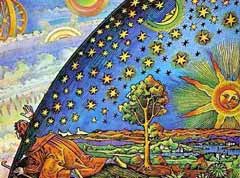

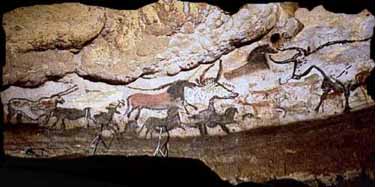

RL: Yes, further and further into the labyrinth would be another way entirely and one that would be a recovery of something long lost. Imagine, thirty-two thousand years ago, Paleolithic peoples ventured into those labyrinthine caves, deeper and deeper and it was then, in the deepest recesses, where they painted the most incredible images on the cave walls. I’m reminded of what Picasso said when he saw the cave paintings at Lascaux: “They’ve invented everything.” Now, why go so deep just to paint images of what is so available on the surface? Why this art at all? It remains a deep mystery. But my intuition tells me that this was not an exercise in rendering life-like images of bulls and horses and rhinos but more the expression of the animal’s role in the primogeniture of the human imagination itself as well as giving expressed vision to the dreams those animals induced in early humans. That’s one reason I think that in these early expressions there are so few human images. The walls are alive almost exclusively with animals. In this there was a kind of rhizomic integrity of world, imagination and dream. I think history can be read as a progressive fragmentation, a violent fracturing into disconnected shards of what must have been a more integral world. We have lost much; but for this very reason, we have much to gain. So, yes, I believe deeper into the labyrinth is the way to that recovery. You know, after writing this paragraph, I had a dream. In the dream,

I see outside a tiger moving along a path. There is a sense that everyone fears the tiger. But I know I must go and greet the tiger and to pet it as I do my own cat Samantha. I do that and the tiger rolls over on its back and I rub its belly as I do Samantha’s when she does that, and the tiger extends its paw to me and I grasp it and we “shake hands.” I can see that the tiger is enjoying this immensely as do I and I wake up with tears in my eyes from the utter joy of this encounter. I don’t have a cave wall but I will find a way to bring this animal into visible manifestation!

PM: What a moving dream! “Enjoyment” is the correct word. The tears make sense as a response to the deep joy of holding the tiger’s paw. It’s a potential connection that we all carry within us, but have mostly forgotten. Russ, there’s something important here—your intuition about Lascaux, combined with the subsequent, powerful dream of the tiger.

It’s as if the dream, though it was not created by you, nevertheless came as a validation of your intuition. Even more, it is as if someone sought to validate your intuition. Let’s take it even one step further: It is as if the tiger sought to validate your intuition. For it’s difficult to escape the impression that there is some kind of consciousness or awareness in and behind these dreams. And where there is conscious awareness there is something personal—i.e., a “personality”— even (or maybe especially) if it comes to us in the form of a Tiger. Of course, we’re accustomed to thinking of our connection with animals either mythically—as in the Book of Genesis (even when interpreted literally)—or as “merely” physical, in the evolutionary sense of “vestiges”: bones, sinews and organs. But the persistence of psyche over time extending as it does as much into the future as it does into the past, therefore permits an extension of “personality” in both directions as well.

This suggests that those Paleolithic artists or shamans who wriggled and squirmed their way down into the deepest caverns for the purpose, as you hinted, of giving form to the animals who made up their imaginal cosmos, probably experienced those very same animals as “personalities”— i.e., persons—living presences who came to them bearing messages, warnings, teachings and blessings. Who is to say that, in those times, they did not in some fashion speak the same language? The animals, after all, were the already ancient “ancestors” of those earliest humans. It might not be too far-fetched to see in these animal persons parading through the human psyche over the millennia, prefigurations of what later humans called “angels.”

…to be continued…