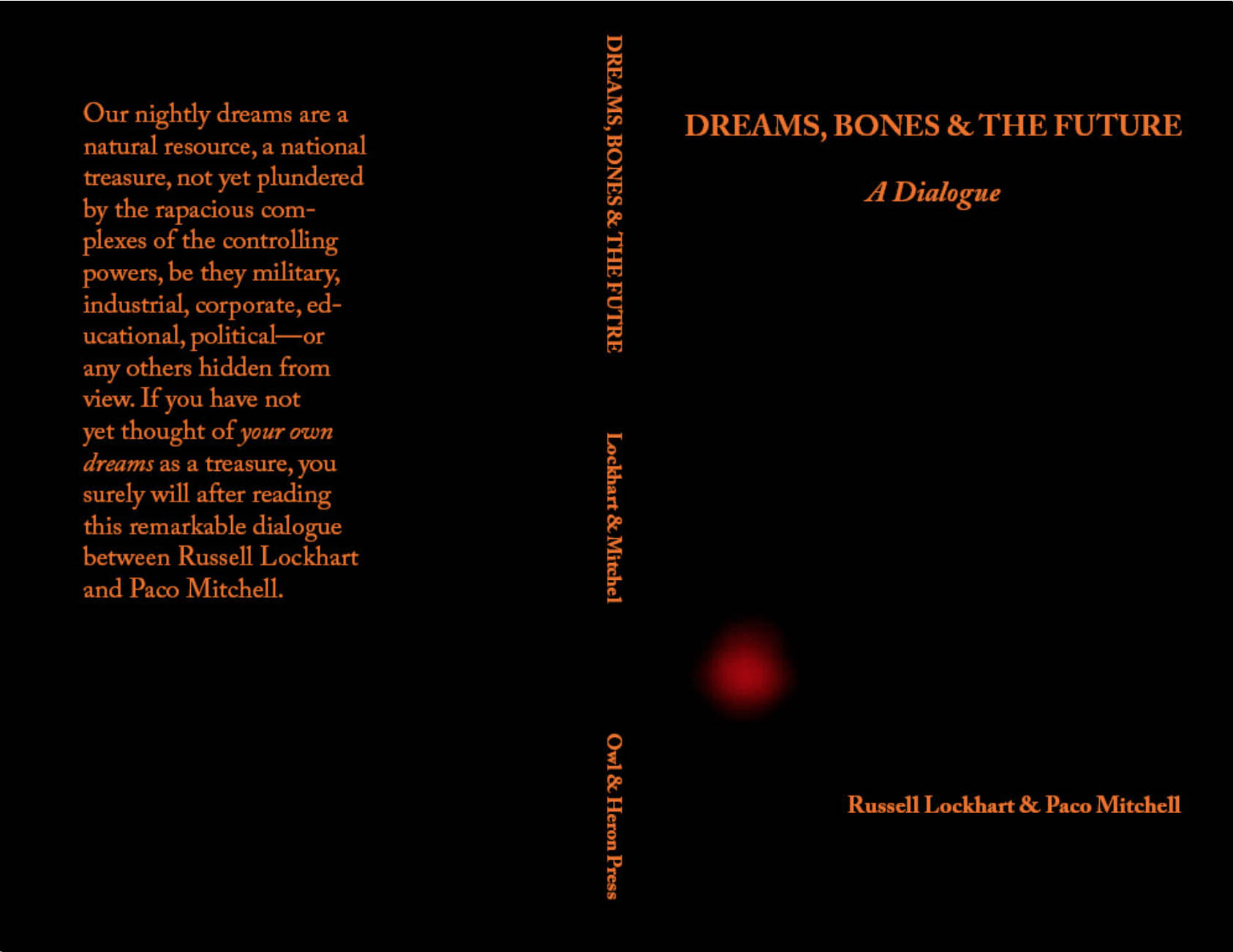

This is the eighth in a series of excerpts from a dialogue between Russell Lockhart and Paco Mitchell.

Russell Lockhart: At the end of our last dialogue, I referred to Goethe’s “method” and how it embodied taking time and engaging in the fullness of the sensorial imagination. What I was referring to may not be clear, so I think an example is in order. This example comes from something that developed into a second “dialogue” between us... and while this has developed into a kind of “play,” it will serve to illustrate the point. It began as I was mulling Goethe at Tully’s, a Seattle coffee shop I frequent. Here is the excerpt from my journal that day:

October 11, 2010. At Tully’s, Fourth and Union, where I go to write when I’m in Seattle—for coffee too. Today, mulling Goethe’s admonition to look at what one sees, to find the story there, I see two trucks. One is a FedEx, the other Costco. Looking, it’s Fe x and Co o—the Tully pillars blocking the actual seeing so readily “filled in.” Across the street there is a Sale, but in looking, only Sal is there. Next door there is STERLING BANK, but looking says it’s LING BANK. Key Bank is also across the street; looking reveals only Key. Those pillars again. The UPS truck goes by and when I look at what I see, it’s UP. Brooding on this nest, I wait for a line, a line from the story, perhaps the first line. It comes.

Sal is a teller at Ling Bank. He does not yet know that Fex and Coo have decided ending it is the key. They have been held up by matters that do not concern us. You may not agree. That’s fine, it is not a requirement. Just wait. You will see. To be continued or not...

I sent this to you, Paco, just as an example of what becomes of the “sensorial imagination.” I was startled when you sent me several pages of “continuation,” which began as follows:

Sal had come in early today, on account of the big brouhaha with Fex and Coo, the bastards. Fex wanted a pow-wow at Tully’s, just like that. So Sal would have to leave before his shift was over. He couldn’t miss this meeting. What do they mean, “it’s urgent”? It’s going beautifully, just the way Sal had planned. Just a few more days, Sal was thinking, a few more lousy days. Did they screw up in some way? Fex was the impatient one, always the big show up front, but in the end he’s the first one to walk. “Coo’s not so bad, just nervous,” Sal said out loud. The teller next to him looked up and said, “What? You OK, Sal?” “Sure, sure, yeah I’m fine. Just talkin’ to myself.” Gotta watch my step, thought Sal. This place is giving me the creeps. Maybe I’ll get outta here now and grab a coffee at Tully’s before Fex and Coo get there. We gotta straighten this thing out....

I responded in turn and we have now continued this “play” for over 100 pages. What is this? The first thing I’d point out is that the detailing of my “looking” experience sparked something in your imagination. This is what Goethe called “exakte sinnliche Phantasie” (exact sensorial imagination), and what I gave free rein to in my experience at Tully’s. It proved generative in your imaginative response and what has followed from it—none of it “intentional” in any usual sense. My experience that day was unpredictable, unintended and unplanned. If I had stayed with what I “knew was true” (FedEx, Costco, Sale, Sterling Bank, Key Bank, UPS), none of this would have happened. If I had dragged back my “looking” to only what was “really” there, nothing would have come of this. It would have been only a list and a list is not a story until it finds entry into the imagination. This is the fundamental nature of Goethe’s method, and why the detail of what is actually experienced (Fex, Coo’, Sal, Ling Bank, Key, UP) is so crucial. It finds entry immediately into the imagination and this in turn generates an imaginative reply as soon as the Urphänomen (as Goethe called it) is told. This “telling” is an embodiment of eros and this is the nature of its generativity.

Paco Mitchell: When you were at Tully’s that day, mulling over Goethe with coffee, the story that grew out of the experience was surprising indeed, and has been generative for both of us. But as you say, it was only because you took the time to put Goethe’s insight into play, in both the conventional and the ironic sense. You put the insight into play—into action— by acting playfully. You invested a portion of your time into a form of play—hardly the nose-to-the-grindstone work ethic we were both taught. The subsequent burst of writing caught us by surprise. Whether it continues or not will depend on our ability to stay in that playful mode, resisting the pull of the “cultural engines” you mentioned last time.

Your emphasis on the unpredictable, unintended and unplanned is a subtle perception leading to profound connections, seemingly hidden, yet plain as day. They are right in front of our noses, but we don’t see them precisely because we have been trained to seek and value the predictable, the intentional and the planned. We learn to reject what is accidental as messy, dangerous and unreliable. Hence, the modern mindset invariably misses what you saw at Tully’s, and what Goethe saw two hundred years ago. What was the big secret? In a word, to look at what you were seeing. But what a gulf seems to separate the one from the other.

This may seem like a thin distinction, but it’s not. For millennia humans have assiduously observed chance events, accidents, the unexpected, etc., and found in them valuable clues as to the inclinations, the creative movements, of the divine, the gods, the spirits, etc. The word accident derives from the Latin cadere, to fall or die. It is related to chance, cadaver, decay, chute, even recidivism. No wonder there has always been a circle of ritual caution drawn around chance, accidental events. One never knows at what point the predictable human world will be disrupted by the capricious actions of the gods. Today, modernity views the ancients with patronizing contempt or amusement, but at least they had the benefit of a cautionary concept—hubris—with which they could remind themselves of their own natural limits.

Today we presume to have overthrown these limits. In our boldness, we believe that the ancient, superstitious attitude has been thoroughly overturned by the modern objective viewpoint. Or so we think. But in our pride we lose sight of Jung’s enantiodromia— the running toward the opposite—and forget that the more we seek and gain control, the closer we come to losing it.

I love the flamenco verse that expresses this wisdom:

Sirva de aviso, Sirva de aviso, Que a mayor confianza Mayor peligro. Let it serve as a warning Let it serve as a warning That at the moment of greatest confidence Lies the greatest danger.

In your humble Goethean exercise at Tully’s you opened yourself to the creative, accidental element of chance that suffuses and surrounds our controlled world. No doubt there are many genies in the bottle you opened, not all benevolent. That’s why propitiatory rituals always attended the approach to the creative. Ancient smiths and founders would only melt or forge metal on certain days... and only after ritual sacrifices. To trespass on the creative was not something undertaken lightly. Therefore, Tully’s. Therefore, coffee of a certain roast. Therefore, just the right chair. The pillar positioned just so. The opening of the laptop. The first sip. The looking. The waiting. The writing. The care of attendance upon the unexpected.

RL: We have titled our dialogue, “Dreams, Bones and the Future”. There is, of course, no “end” to such dialogue. But perhaps, with the advent of “Fex and Coo,” a goal we neither specified, nor planned, nor announced, has been achieved and so it may be time to bring this portion of our dialogue to a close. I can think of no better way to do this than to make reference to Goethe’s experience of meeting himself, that is, a far-into-the-future self. I’m thinking of him riding his horse on the road to Sesenheim, and he “sees” a horse riding toward him, carrying an older Goethe dressed in clothes quite different than he was actually wearing, clothes he did not own. Years later, he is once again riding the road to Sesenheim, and realizes that— without plan or intention—he is wearing the exact clothes he had seen in his vision years earlier. He is now the figure he saw. What I “saw” at Tully’s has become an unplanned, unintended, accidental future. Whether through this Goethean “looking” at what we are seeing when awake, or whether further engaging the images presented to us in the night world of dreams, we are witness to the seeds of the future.

PM: Throughout the course of our dialogue we have been trying to straddle a gulf that seems to widen by the day. Our effort might seem comical to some, as our feet get farther apart—picture Laurel and Hardy working as lumberjacks on a log pond, each foot on a different log, the logs drifting farther and farther apart. To others the seriousness of our intent should be evident.

The gulf we’re straddling, of course, is the distance between the primordial, innate gifts of the human imagination, psyche or soul and the kind of imagining that will be required of us in the future. What separates the two is the modern, objective outlook which depreciates imagining, deep seeing, in all but very restricted areas. Goethe, as you have observed, was ahead of his time, and the subsequent development of the scientific method—especially the scientific “attitude”—rendered Goethe’s views on science and knowledge “obsolete.” Only recently are his writings being revived and modern scientific “knowing” beginning to catch up.

The unexpected outbreak of Fex and Coo into our shared consciousness may have been incubated by all our musing and brooding over the Neanderthals, the Inklings, the artists at Lascaux, the shamans dancing, weaving, calling. Ironic that writing about something led to something else entering the writing. Perhaps that’s what Lorca’s rose was seeking, that “something else.” And perhaps, as you suggest, the exercise of our imaginative capacity, free of excessive intentionality, may lead us—each of us, individually—into the future that we’re capable of, at our best. That’s more or less what I think the idea of “angels” implies: The future coming to meet us, helping us to imagine our way out of the traps that encumber us, freeing us to discover those further possibilities.

We must not forget the critical element in all this—the Eros commitment to give our love to what exceeds our understanding. This amounts to giving the gift of our gifts back to the original donor—the circular interplay of creature with creation.

RL: At the end of my little Goethean exercise, I wrote: To be continued or not... While these dialogues have been between you and me, I find myself wondering what psychic wanderings, imaginal by-ways, dreams, synchronicities and such these dialogues may have stirred up in our readers. Let’s invite others to join in, an Eros invitation if you will, to participate in further installments of Dreams, Bones and the Future.