This is the fifth in a series of excerpts from an ongoing dialogue between Russell Lockhart and Paco Mitchell.

RL: At the end of our last dialogue, I was saying that from a large cultural perspective we may be entering a new nomadism. I think the Internet is an example of this, where we can travel the world of places, ideas, time—most everything—in an “instant”. Perhaps the greatest danger is in not taking time to dwell in anything, but rushing off to “the next” as quickly as we arrived. We may indeed sacrifice what Keats called negative capability, when one “is capable of being in uncertainties, Mysteries, doubts without any irritable reaching after fact & reason”. It is not possible to dwell in these geographies Keats refers to if time loses “duration” in our experience. Yet, even if one is able to stay in such spaces for a time, there too we find a kind of nomadic wanderlust at work, for in that space, the portals of imagination, like gateways, open to a “new world”, one opens to exploration in ways that are only hinted at by what we have mentioned so far in these dialogues, and even more so by that to which we have not yet spoken. Dreams, as I have tried to make clear, are “calling” us to “explore the future”, to enter into the rhizomic womb and to participate in the birth of what is to come. In this sense, dreams are nomadic prods, urging us on.

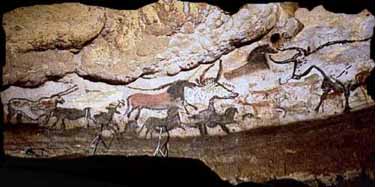

As I was mulling this over, I fell into a liminal state in which I was traveling with a group of prehistoric figures— perhaps Neanderthals—producing a frisson of uncertainty as to what I was in this context. I could not tell, knowing only that I “understood” what was being said and that we were traveling to a “council of dreamers”, as the leader explained.

As I came out of this imaginal state, I felt that this was one of those “hints” that we have not yet explored, that has that strange quality of a root in long lost history and yet speaking to “the future” in some way not quite explicable. So, Paco, what does the image of a “council of dreamers” from prehistoric time conjure up in you?

PM: As usual, your words and images have the effect of a blacksmith’s hammer on the anvil of my mind, and associations go flying in all directions, like sparks from red-hot iron. I hope I can do partial justice to at least some of those sparks as I chase them hither and yon.

You point out a dichotomy between two levels of the “new nomadism”. On one side, there is a fruitful seeking after new and even old but always lively ways of seeing; and on the other, a restless but sterile gaze upon mere objects. The first strikes forth in revolutionary ways, while the second turns in grooves of deadly sameness.

Why should we use the term “nomadism” to describe both phenomena? Partly, I think, it is a result of how undeveloped our language is in describing the subtleties of psychological experience. We have become so accustomed to what Blake decried as “Newton’s single vision”, that we forget there are two ways of seeing— merely looking at vs. truly seeing. When we only look at something, all subjective awareness resides within us. But when we truly see something, what we see addresses us as a living subject in its own right. Rilke recognized this phenomenon in his poem “Archaic Torso of Apollo”. At the end of the poem, the marble torso “still suffused with brilliance from inside, like a lamp” spoke to Rilke, in effect, and said: “...there is no place that does not see you. You must change your life”.

Of these two modern nomadisms, I know that you seek what we might call the “higher”, or revolutionary, nomadism. That is why you allowed yourself to dwell in the negative capability long enough to drop into that timeless reverie in which you walked with a band of Neanderthal hunters, all on your way to a “council of dreamers”. Had you hewn only to the mark of the lower nomadism, you would probably be up to your ears in electrodes, standard deviations and control groups. As it is, you have hewn to the mark of your own experience.

I accepted your challenge to respond to the “council of dreamers” image. Consigning myself to negative capability, I dropped into my own reverie. I saw myself born along on the wings of a large heron, as if I was riding on its back. The heron and I flew toward the Neanderthal band and on to its “council of dreamers” When we arrived, I saw—or felt—that the dreamers formed a circle, the only configuration that made any sense. As I tried to feel my way into the goal of their council, the aim of their meeting, I was surprised to find that what they sought was... the future! This was so startling to me that, at that point, the vision ended.

However brief and evanescent it was, this imaginal experience has given me much to contemplate. How ironic that, in our efforts to chart ways into the future, you and I both have fallen back on styles and methods of consciousness thousands of years old, only to discover that our Neanderthal counterpart—at least insofar as my imagination could see them— were seeking a pathway into the future, as if they sought to meet us halfway!

Also, I find myself wondering to what extent the heron and I are separate, distinct beings. Whether I say “I flew” or “we flew”, is there a difference? Are we discontinuous phenomena, as the modern outlook would have it, or are the two of us really one, parts of one integral unity? This would be an archaic mode of “thought”. I suspect that mysteries lurk behind these questions, which the modern outlook is ill-suited to answer. I know that imaginal experiences are susceptible to any number of reductive criticisms, as if they were only this, or only that. But years of living with the negative capability required to delve deeply into dreams has long since taught me to proceed in all such exploratory ventures in the provisional spirit of— as if.

RL: Your reference to their seeking us as we seek them reminds me of Robert Sawyer’s wonderful Neanderthal Trilogy: Hominid, Human, Hybrid. Here is one artist who is fictionally pursuing this very territory. Who knows what future “hybrid” consciousness might develop if we recovered the deep roots of “knowing” that these people had? Aren’t we seeing a version of this in modern science when—freed from the confines of that Newtonian single-mindedness— we are freed to recover the wisdom of earlier traditions? Do we not see something of this in Avatar, James Cameron’s vision of the hybrid possibilities of human and alien?

This “going back”, in what ever manner, is an essential move in “going forward”. It characterizes the point of the new nomadism. Modern humans, for all our overall advancement, can hardly be described as fully “at home”. Half the world is fighting over “homeland”, and we all are witness to the ecological warnings that picture our earthly home in grave danger. So the new nomadism appears in many forms from impulses to “find meaning” (as old institutions crumble), to exploring dreams, imagination, and the far reaches of mental states, to our incessant nomadic “browsing” the internet.

If we focus on the word itself, nomad, we can see how this works. Nomads have no fixed home as they are constantly “seeking” food, water, shelter. The word came from the Greek nomos, from the Indo-European root nem- containing the fundamental image of “wandering”. But wandering is not “lost”. It is the stark “lostness” of the modern, post-modern, and contemporary conditions that claim there is no meaning, that dreams are random, imagination is illusion, and there is only now. True wandering is, ironically, a dwelling in the unknown of the future, the uncertainty of “next”, and moreover a kind of “appetite” for what Keats called the “Pentralium of Mystery”. Keats captured this sense in his “negative capability”, as did Rilke in his line, “There is no place to bide”. (Yes, it’s “bide” as in to bide one’s time, to wait, to dwell.)

If we focus on the etymology of the word “future”, it’s prehistory, we find the root bleu-, meaning “to be”, “to dwell”, “to grow”. In Greek this came to be the word phulon which referred to the “tribe that dwells together”. Of course, the future is “what is to be”, where we will dwell, that place we will “grow into” together. I love how “looking back” into a word’s roots, reveals so much. And this is a rhizomic layer each of us carries whether we know it or not.

By “going back” to the prehistory of the word “future”, we can gather up some intriguing images that begin to give more “body” to the word. I’m sure that “going back” into earlier consciousness would similarly give birth to experiences that would likewise give body to our wanderings in prehistory. I believe it is important, as the word itself conveys, that we do this together. In this regard I’ve been wondering whether the “social networking” craze (Twitter, Facebook, MySpace, etc.) is perhaps a step in this direction of non-hierarchical collective effort.

So how do we do this... new community? I think that most of us have an immediate problem with this because our consciousness is so filled with intention (or shoulds, oughts, can’ts, etc.) we get stopped from doing anything at all in this direction. So first, I believe, dropping intention as fully as possible is one way to dwell and wander in unintentional space. This cutting the moorings to our sense of “us”, becomes the potential for our experiencing something “other”. Being nomadic, after all, means leaving what we know and moving on into an unknown “something else”. This is the state I think we are talking about in these dialogues. Listen to how Lorca expresses this:

Casida of the Rose

The rose was not searching for the sunrise: almost eternal on its branch, it was searching for something else The rose was not searching for darkness or science borderline of flesh and dream, it was searching for something else. The rose was not searching for the rose motionless in the sky it was searching for something else

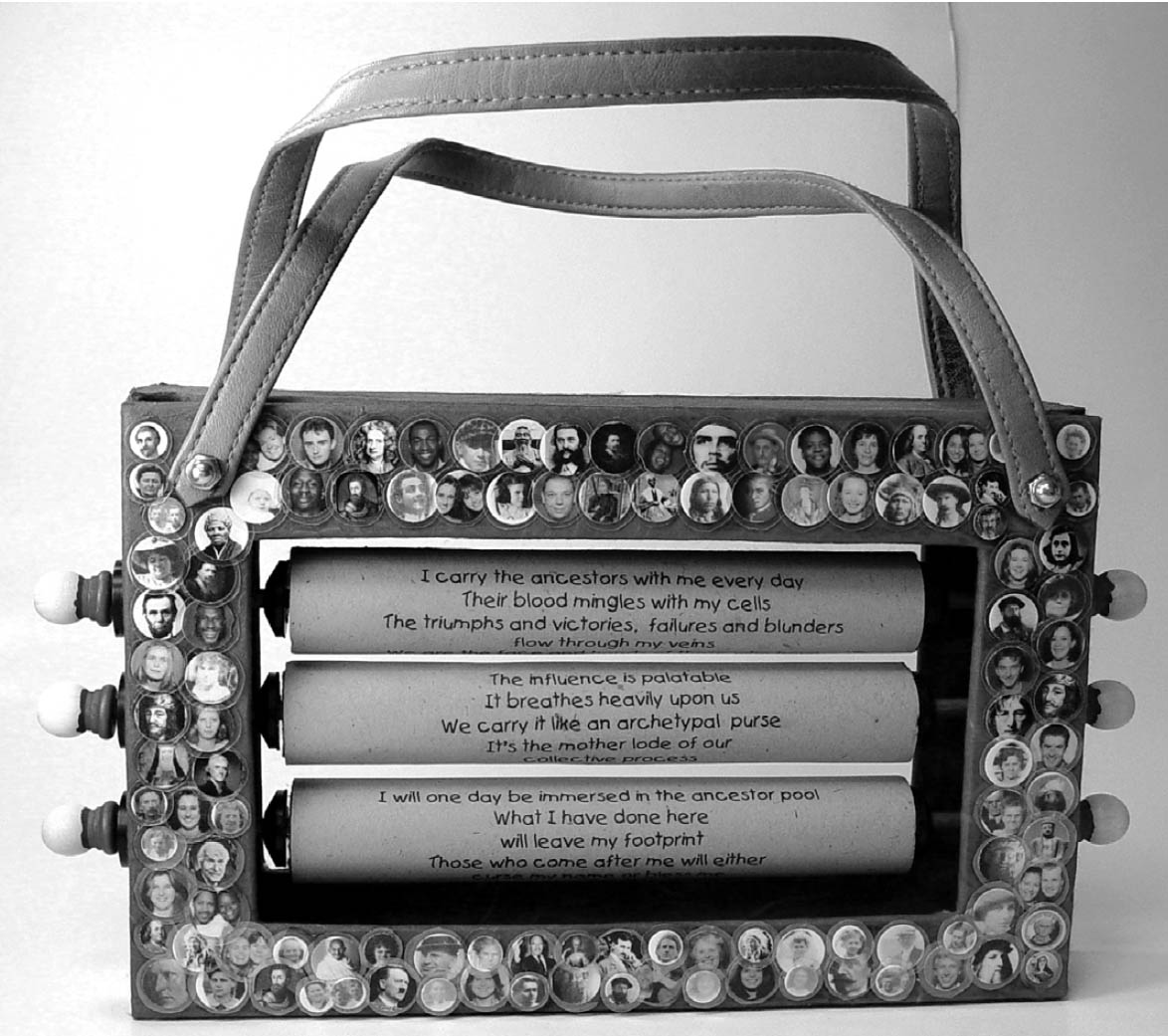

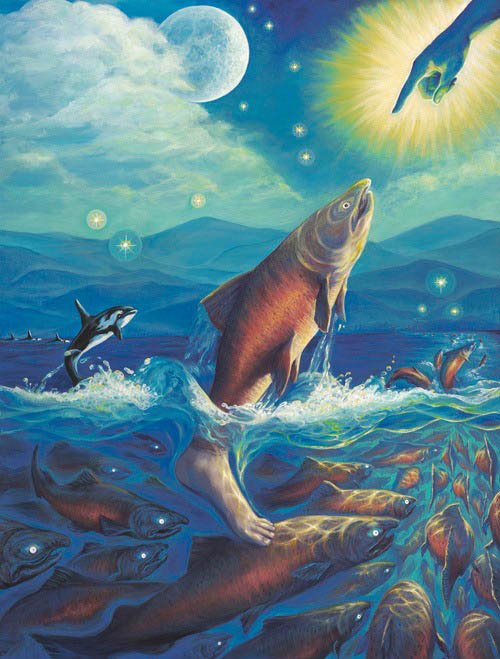

One of the ways I do this searching is through what I call “accidental” gesture. A specific example is to take coffee and a large sheet of soft absorbent paper and spill, splash, throw, drip, drop, smear, etc., without any “intention” to “make something” specific. After the sheet dries, I come back to it and begin not to “merely look”, but to “truly see” as you call it. What has been given form (“birthed”) in these accidental gestures? Here I include an image that was “found” in one such effort before we reached this point in our dialogue.

This is from a collection of such found images with accompanying “word gestures” I am calling, Foundlings At Large.

We can talk about what I or anyone else might “project” into the “accidental image” as bringing out some aspect of our subjective state. I have no problem with this idea unless it is used as an “explanation” for what one sees. This is the single mindedness you referred to as Newtonian. But if we follow Goethe’s notions, and Rilke’s admonitions, and Keats’ insights, then we deepen into the experience, through a participation with what is there. What is important, crucial and so often missed, is being penetrated by the image, a genuine intimacy with the otherness of the image, and decidedly not “only” or “just” a solipsistic relationship with oneself.

PM: “To be penetrated by the image, a genuine intimacy with the otherness of the image”. What a radical concept, Russ! This is exactly what we have spent centuries protecting ourselves against, the autonomous imagination, which came to be seen as a threat to our project of controlling nature (or, as Francis Bacon put it, “vexing” nature) in order to force her to yield not only her secrets, but her bounty, far beyond what she spontaneously gives us of her own accord. And so we seek to “conquer” and “dominate” not only the natural world but our own inner lives as well, as if we were at war both with ourselves and the world. What a tremendous inner divisiveness besets us. And, far from quelling the disturbance, we fan the flames and set one another’s teeth on edge.

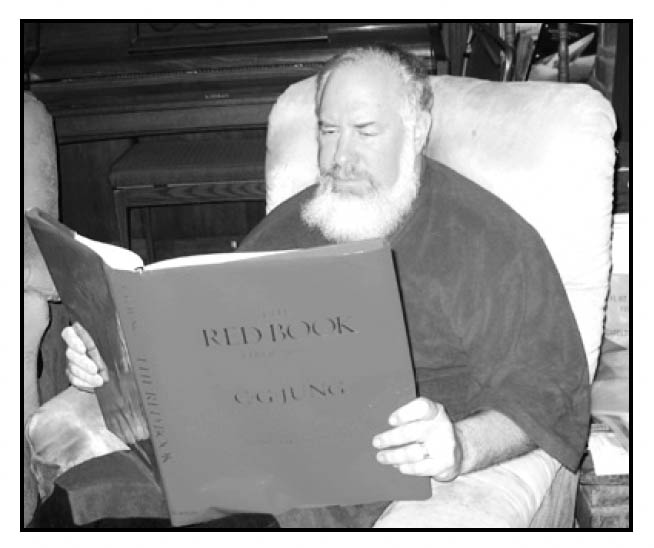

But like Lorca and the rose, you are calling for “something else”. Instead of warfare, conquest and dominion, you evoke something erotic, a passionate yielding to the beloved, allowing oneself to be penetrated by the image and its otherness. This amounts to a prescription for a massive healing process, a virtual restoration of our inherent religious sensibility, our natural birthright. That’s why Sawyer’s reflections on the Neanderthals ring true. He seems to be focusing on inherent, evolutionary gifts that we, throughout our centuries and millennia of hubris, have lost track of. Jung used to cite what he called a “classical etymology” of the term religion: “a careful consideration of the effects emanating from the unconscious”. Your phrase of allowing oneself to be “penetrated by the image” says the same thing, in language favored by artists.

Your “accidental gestures”, those spilled-coffee paintings, images seen in driftwood, and so forth, show to what extent we are surrounded by clues and hints of that “other world”. I once wrote: “The beaches of our sleep are studded with the note-stuffed bottles of dreams”. Well, as you show, it really takes very little to shift from one reality to another, just that twist of attitude, away from hard-driving intention toward the moment of uncertainty, dwelling there, paying attention to what appears, like taking a breath, and pausing. This is how epiphanies happen: just that momentary pause, and staying with it. It’s amazing, when you think about it, how close the boundary is between apocalyptic destruction and creative renewal. But it does require a subtle shift in individual awareness to take place.

RL: I’m glad you mentioned “as if”. I don’t think this notion has penetrated deeply enough. It was Benthem who wrote his “theory of fictions”, and then Vaihinger, who wrote his “fictionalism”, and the psychoanalyst Adler, who wrote of “fictions as a final goal”. Strangely, Jung does not refer to Vaihinger, though James Hillman has righted this by combining the streams of Vaihinger and Adler with his own contributions resulting in his “healing fictions”. In one way or another, these efforts are working away from the literalism of so-called “reality”, and putting forth a valuation of the fruitfulness of the image and of the imagination. This is the difference between “merely looking” and “truly seeing” you referred to earlier. “Fiction”, in whatever form, is a way of “wandering” and “dwelling” and as such, is a means of “revelation” that so-called reality and the real world does not yield.

The fiction of dreams is a prime example. When “reduced” only to reality concerns, they will lose their deepest value to us. But a dream leading us into the future: there is its deepest concern. You saw this in your own imaginal experience of the “council of dreamers”. Rilke certainly had something like this in mind when he says, “You must give birth to your images. They are the future waiting to be born. Fear not the strangeness you feel. The future must enter you long before it happens. Just wait for the birth, for the hour of the new clarity”.

Here is an example of future enterings from another angle. Earlier in this dialogue, you said that my images had the effect of “a blacksmith’s hammer on the anvil of your mind”. Even though I cannot really “claim” the images as “mine” in any proprietary sense, I loved your expression. I knew that your image of the hammer and anvil and the blacksmith “hit” me. It was some time later, in the shower one evening, that I heard a voice announce with clarity: “hope is the anvil of evil”.

This is what I call a “presentational” experience. By this I mean that if one begins to “truly listen” to what one “hears” (similar to what you referred to as truly seeing as distinct from merely seeing), then the effort to “reduce” this experience disappears in favor of what I think of as “gleanings”. I wrote of this a long while ago in a paper called, “Mary’s Dog Is An Ear Mother”, which came from the voice of a hospitalized schizophrenic patient. I illustrated there what can happen when one truly listens to “the voices of psychosis”. Very often, these presentational experiences will find their way into poetic expression, not because one is or tries to “be” a poet, but because that is the form in which the listening goes. For example, this is what happened in response to hearing that line in the shower.

Evil’s Anvil

The voice whispered

words not echoing

off the shower walls not

drowning in the pulsing flow

but repeating as if mimicking

the alarm this morning in

not quite sing-song

but something like

Hope is evil’s anvil...

Hope is evil’s anvil...

Hope is evil’s anvil...

until I echoed aloud

asking the questions

What then is evil’s hammer?

What then is being forged?

Who then is smithing?

Then I thought

if all attention is fixed

on evils loosed from

Pandora’s jar, and only Hope

remaining becomes evil’s anvil

What then?

Hesiod does not tell, nor

anyone else; everyone is silent.

But now I can hear the clanging

metals as they collide in there.

I invite anyone to respond to the questions posed. I wrote out these lines here not as a poem, and not as a poet, but as a “witness”, to illustrate the kind of poetic response that “flows” from the reverie on the line in the shower. I was not “making this up” so much as writing it out as I “heard” it— although it was not so much speech I heard as the “sound” of words “gushing forth”. I don’t expect this to make much sense; in fact, I’m not trying to make sense at all, but simply to “tell” in that sense I’ve written about elsewhere: eros means telling. Now I have to admit that I have in the past studied a good bit of Hesiodian scholarship and am aware of the myriad interpretations of Pandora’s actions and the meaning of Hope’s remaining. But I was not thinking any of that as these lines poured forth. In fact these mages would be a rather new approach to the underlying questions the myth propounds. I don’t want to go there, as the main point is to illustrate the “spark” and its effect that your words evoked in me, and became, in Rilke’s sense, a place to bide.