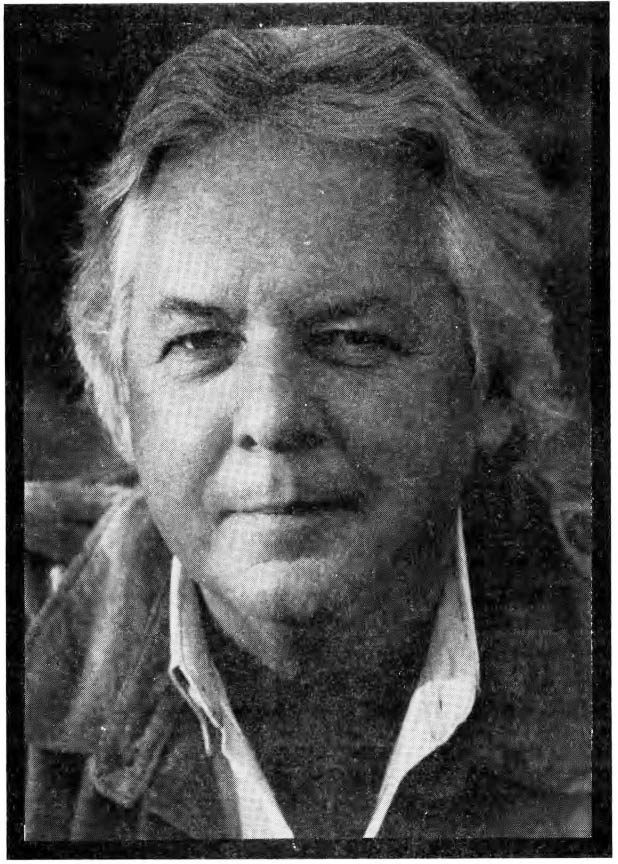

DNJ: How did you first get interested in dreams?

Henry Reed: I recorded my first dream in 1968, when I was a graduate student at UCLA. A student friend had inspired me with the dreams he shared with me. His dreams were different than what I was learning about in school. In my psychology classes dreams were seen primarily as medical samples to be used by professionals for the purpose of diagnosis. But my friend was having dreams that he used himself for inspiration and guiding his life.

DNJ: Didn't you teach dreams in a university setting yourself?

HR: Yes, in 1970, I began as an Assistant Professor of Psychology at Princeton University. I saw the possibility of combining dream research with a human potentials vision.My first dream project concerned a humanistically designed experiment to improve dream recall. The students and I explored what happens when people try to improve their memory for dreams. No one had ever tried that before, especially with a humanistic approach involving full disclosure and collaboration with the students, who were the participants in the study.

DNJ: What did you learn about improving dream recall? Anything we can share with our readers?

HR: You can learn the ropes but not use them if you're not motivated to do so. We discovered that there is both a skill factor and an effort factor in dream recall. People can develop dream recall skills, such as lying still in the morning and writing down whatever comes to mind. But lacking proper motivation they won't spend much time using those skills. We published in 1974 our study in the Journal of Humanistic Psychology, showing that given special incentives people can demonstrate dream recall skills they had learned.

DNJ: Did you do any work on dream interpretation in the university at that time?

HR: About the time I began teaching at Princeton, Fritz Perls was doing dream symbol dialogues at Esalen. His work would ultimately open up dream interpretation technology to the masses because he was the first person to practice a specific dream interpretation technique in public for all to see. We could experiment with his method and learn from it.

In my course on Carl Jung, for example, we married Fritz Perls' dialogue method to Jung's symbol amplification perspective. We would interview a dream symbol to learn its meaning.

Gayle Delaney, by the way, who has since become well known for her dream books, was a student in that class. She developed her "Dream Symbol Definition" method from our work in that course on Jung.

DNJ: I know you spent some time at the Jung Institute in Zurich. How did that affect your work with dreams?

HR: It's hard to say. When I went to the C.G. Jung Dream Laboratory in Zurich, during a sabbatical from Princeton, I went there to work with Carl Meier, who had written about Asklepios, the Greek god of healing in dreams. But I was surprised at the mechanical approach he took to dreams in that lab. He had people sleep in a cold room to see if they would have more active dreams to warm the body. He had no conception of a humanistic approach to research. I wanted to help people incubate healing dreams. He was against it, so I came home and did it on my own.

DNJ: How did you do that?

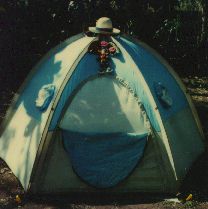

HR: My dreams initiated me into recovery from alcoholism, so I had some personal experience about how they worked in that way (the story of this healing appears in my book, Getting Help from Dreams). I had also had a series of dreams that provided some of the details that I used to develop a dream incubation ritual. I wanted to do this work in a setting outside the laboratory and I got myself invited to the Edgar Cayce summer camp, where dreamwork was a regular part of the activities. I created a "dream tent" for people to sleep in. I asked them to decorate the tent with their dreams and I helped them to prepare for a special dream.

DNJ: Did it work? Did people have special dreams?

HR: Did they ever! They had past life dreams, out of body dreams, things that I had never experienced myself. I was in awe of what was happening. Frankly, it was over my head. I was not spiritually awakened enough, or mature enough, to deal with what was going on.

I wrote an article about the work up to that date, and the Journal of Humanistic Psychology accepted it, in 1974, without any changes! That was flattering. But what I wrote enraged the faculty at Princeton. They terminated my contract, which was an unusual move, and caused some dissension in the department.

DNJ: What got them so upset? They didn't like dream study?

HR: It wasn't the content that upset them, it was my experimental method. I wrote in that article that if you wanted to obtain such dreams in psychology experiments, you couldn't conceive of dreams as being the result of a mechanical process. I proposed that we need to view dreams as an element in a storyline, involving an autonomous, transpersonal awareness, and that the best way to provide a context to develop that story line was using a symbolic ritual, not a mechanical technique. The folks at Princeton took that to mean that I was subverting the scientific process.

DNJ: That must have been frustrating for you, especially if the Journal of Humanistic Psychology had been so enthusiastic about your paper to have published it unedited.

HR: Well, I was terribly hurt, yes. But also, I felt overwhelmed by what was coming out of the dream tent, so I wanted to stop it anyway, until I could grow into it. That was back in the period of 1974-1976, and there wasn't the same climate of understanding and support as we have today for that kind of alternative reality.

DNJ: Well, I'm sure the dream tent would be popular today. It suggests that dreams are a doorway to all the alternative consciousness manifestations people explore these days.

HR: I felt that I helped open up a hole to the heavens, so to speak, so that divine energy could manifest in dreams once again. I was pleased when, in 1983, A psychiatrist named P. Richard Gunther, published an article in the American Journal of Psychotherapy, "Religious Dreaming: A viewpoint," in which he credited my dream incubation work with demonstrating that God was alive and well in dreams. But at the time--this was around 1974--I backed off that intense shamanistic relationship with people, and took more of a coach-like attitude. I let people create their own sacred space, create their own dream tent substitute at home--the personal dream diary.

DNJ: You continued to research dream incubation, but in a different way?

HR: Yes, exactly. The Edgar Cayce Foundation commissioned me to create a home-study research project on dreams. I was excited by the idea for two reasons. One, I got to develop the approach of conducting research with people in a humanistic manner by having them work on self-help projects at home. That approach has proven very effective, and in the years since, many others have adopted this synergistic approach to awakening consciousness through research. Also, I was interested in exploring Edgar Cayce's basic hypothesis about dream interpretation.

DNJ: That sounds intriguing. What did he say about dreams?

HR: It's not so much what he said about dreams, but about how to learn to interpret them. His basic idea was that it is easier to learn to interpret dreams if you have a reason to use them for something constructive. If you try to apply your dream insights to making constructive changes in your life, he proposed that dreams would respond to your efforts and help you learn to interpret them.

DNJ: That sounds like the dreams would be active from their end to meet you half way if you would get off your duff and do something about your dream interpretation instead of just thinking about it. Is that the idea?

HR: Exactly. Hugh Lynn Cayce, Edgar Cayce's son, is quoted as saying, "The best interpretation of a dream is one you apply." Just as Montague Ullman developed safeguards so lay people could work together on their dreams, so Edgar Cayce had proposed a safeguard for individual dream work. It was testing a dream interpretation through application.

DNJ: So how did you implement that philosophy into your home study research project?

HR: I created a "Dream Quest" workbook. It took the idea of the dream tent and spread it out over four weeks, with a weekly cycle of dream work. The adventure began by a person gathering dreams for a week while thinking about various areas of life that could be improved. Then I created some dream interpretation exercises that helped the person collaborate with their dreams to choose a project to work on, such as having more fun with the children, or getting along better with the boss, or improving personal morale. The exercise helped them to develop a strategy based upon their dream interpretations, then try it out for a week while recording more dreams. The second week's dream interpretation work focused on getting feedback from their dreams on the use of their strategy. From that work, they developed a revised strategy, and so on, continuing to look to dreams for new insights to apply and then getting feedback from the dreams about that application.

DNJ: It sounds like it created the possibility for a relationship to dreams that would make for an ongoing drama. Did it work?

HR: It sure did! At least for those who saw it through to the finish. There was a discipline involved. About one-third of the approximately 2000 people we enrolled finished the project. Most of them had very positive stories to tell. The dream interpretation exercises worked to provide applicable insights. Many people told about how they had made significant progress on their personal issues. I was very pleased. I published in 1978 a report on this work in the Journal of Clinical Psychology. It was the first study of its kind to demonstrate that it is possible for lay people, working on their own at home, to make constructive use of their dreams to improve their lives.

DNJ: The average person isn't sure that they can deal with their dreams, so your results seem pretty important for them to know about.

HR: Well, yes, but even more important back then was what that study meant for the dreamwork movement itself. Prior to that, the usual comment from professionals, like psychologists and psychiatrists, was that it's best not to encourage people to look at their dreams because they are liable to stir up problems for themselves. Professionals are not so likely to say that today, and that's the result of changes brought about by the dreamwork movement.

DNJ: I read somewhere you being called the "father" of the dreamwork movement. How did you get that title?

HR: I don't think that I really have that title, but it comes from a passage in a book by Jack McGuire, one of the early participants in the Dream Network Bulletin. In his book on dreams, Night and Day, Jack describes my work creating the Sundance: The Community Dream Journal, and how it led to DNB. If there is any truth to my parenting the dreamwork movement--and actually there were many parents--it comes from the power of the press. The very existence of the Sundance journals, regardless of the content within them, spoke loudly about the birth of a movement.

DNJ: Tell me about the Sundance journals. We've heard of them referred to often, but have never seen one.

HR: Well, I guess they are collector's items among historically minded dream workers. It grew out of that home study project. People wanted more. I saw that people had stories to tell about how they had used their dreams. I had a series of dreams, a couple involving the word "Sundance" and related archetypal imagery involving the theme of "The Many and the One," suggesting that we could create a UNI-versity of dream students, sharing their explorations into dreams. So I created the journal just for that purpose. Before professional dreamworkers had any kind of forum for scientific exchange, the Sundance journals provided DREAMERS with a forum to exchange ideas and experiences, to create a body of knowledge and expertise about dreamwork. The publication acknowledged that ordinary people can have a personal relationship with dreams and learn from one another's experiences. It is the equivalent of the public, scientific enterprise, but on a popular level.

DNJ: Wow, I can see how that would help launch a movement, because it would empower people. The press has a lot of power to give the people a voice.

HR: Exactly. And Sundance gave people a voice about dreams as being more than just a medical sample. Most of the things that professional dreamworkers explore today were first mentioned by ordinary dreamers in the Sundance journals. There were six issues, published from 1976-1978. They were subsidized by Atlantic University. When funding ran out, Bill Stimson, who was big fan, started up Dream Network Bulletin to carry the torch, the same torch you are carrying today.

DNJ: Well, you carried the torch yourself, I know, because you were an editor of DNB for a couple of years, with Bob Van de Castle, an enthusiast of dream telepathy. Didn't you develop some kind of dream telepathy experiment that emphasized community dreaming?

HR: I did, and it probably is one of my dreamwork inventions that is going the strongest today. We call it the "dream helper ceremony."

DNJ: We published an article or two about that ceremony in DNB. Tell us about it. How did it come about?

HR: It was a serendipitous finding. When I had the dream tent up at camp, I noticed that often the kids in the camp would dream about the person sleeping in the tent. Sometimes it wouldn't be obvious to anyone but me, who knew about what the person in the tent was dealing with, so I could recognize the themes in the other kids' dreams. It seemed to me that here was a case of spontaneous dream ESP that was occurring on a regular basis, a rare bird in the ESP literature. I wanted to see if I could create an intentional experiment that would bring about the same results. I had had a dream of my own about the power of a circle of dreamers to guide me. I also worked with Bob Van de Castle because of his experience with dream telepathy, and together we created what we called the Dream Helper Ceremony. That's how it came about. To describe it, what you have in this ceremony, is that a group of people promise to dream about the undisclosed problem of a someone in distress. It's almost like a group of Good Samaritans, who offer help to a stranger in distress. Over a period of some twenty five years, myself and many other people who have tried this experiment have found it very successful. It's fitting, I suppose, that DNB has published accounts of it, but when Van de Castle and I submitted an article to the journal Dreaming, which is very concerned with its academic standing, they wouldn't publish it.

DNJ: Why not? What are the results that are so controversial?

HR: Well, the experiment began as a humanistic alternative to standard ESP experiments, so it has this parapsychological background. But the dream helper ceremony also stands on its own as a community dream process. Basically, what happens is this: No one dream usually seems very pertinent. But the group finds patterns in the dreams that enables them, usually, to correctly diagnose the person's problem, even though they never knew what it was until the experiment was over. Mark Thurston, who is now an Executive Director of the A.R.E., got his doctorate at Humanistic Psychology Institute, under Stanley Krippner, for his scientific study of that one finding in the dream helper ceremony. Some people will accept, and some people will not, that kind of evidence for ESP. But what I find more interesting is the more transpersonal dimension to the group dreaming process.

DNJ: What do you mean by transpersonal?

HR: It means finding something transcending the personal within the personal itself. In the dream helper ceremony, what we find is that the pattern of imagery in the dreams points the person's problem, but doesn't really provide any help to that person. The purpose of the ceremony is to help the person, remember, so we need to go farther. People question whether you can really dream for someone else, or if dreams have any external, objective value. Well, the answer we get is that if people will interpret their dreams for what they are learning about themselves, then their insights really do contain helpful advice for the person they were dreaming for. It is as if each person in the dream helper circle telepathically tuned in on the person's issue, saw it in terms of their own issues, and their dreams responded to the resonance by suggesting how the dreamer should work on his or her own related problem. That is the transpersonal element--each person found the distressed stranger within themselves.

DNJ: That seems to be a theme in dream groups. As in Montague Ullman's dream process, where each member of the group can relate personally to the dreamer's dream.

HR: Exactly. And in the Dream Helper Ceremony we have an alternative to the Ullman group method, not better and not a substitute, but an alternative way to have a group of lay people, even strangers to one another, work together constructively with their dreams. Today, many people who have experienced the dream helper ceremony go on to share it with others because of its power, even for the uninitiated.

DNJ: What do you mean by uninitiated? People who don't believe in dream telepathy?

HR: I mean that you can take a group of people who have no prior dream experience, and, without trying to persuade them of any assertions about the value of dreams, the meaning of dreams, or anything other assertion about dreams, you can let them see for themselves. All you ask of them is this: Are you willing to keep a promise? Are you willing to lend a hand to someone here in our group who is confronting a life challenge and asks for your help? If so, then get a volunteer in the group, who doesn't say what their problem is, and have the people in the group promise to remember a dream for that person that night. That's all. I've done this experiment with Elderhostels, where you have senior citizens who haven't remembered a dream for ages. They can relate to the premise of the experiment. They doubt their ability to remember dreams, but remember them they do, because they've made a commitment. They don't think their dreams amount to much, but when I ask them to examine them in their group for common themes and come up with a diagnosis of the person's problem they were dreaming for, they do it and they surprise themselves at how accurate they are! They see that their dreams have value, that they contain helpful information.

DNJ: It seems incredible that people can actually direct their dream to an invisible target. How do you think they do that?

HR: That's a good question, and has sent me off onto a new research direction. Several years ago I gave an invited address about the Dream Helper Ceremony to the annual convention of the Association for the Study of Dreams. Bob Van de Castle and I had conducted several workshop demonstrations of it at prior conventions, and now they wanted to hear from me about how it worked. As I was explaining in my talk, research psychologists have developed several high powered technologies to influence dream content in the laboratory--hypnosis, pre-sleep suggestion, sensory bombardment, and so on. It only works to a limited degree. Dreams seem to have a will of their own.

DNJ: I think that's an important point. What makes dreams so valuable is that they have a mind of their own. They aren't just little stories that we crank out.

HR: Exactly. What I realized while I was up on the podium giving that talk, explaining this history of dream research, was that in the years that I had conducted Dream Helper Ceremonies, none of the participants had ever asked me, "how am I supposed to dream about someone else's problem, much less when I don't know even what it is?" It seems like such an obvious question, but no one had ever asked it. And, I realized, if they had asked it, I wouldn't have known how to tell them. It was like a mind-blowing light exploding in my head--we had never given them any instructions on how to do it, we never used a single technique. I realized that it was their intention to do so that carried the day. They simply did it intuitively.

DNJ: Dreams are pretty intuitive. We don't usually think of that fact, but they are one of are greatest living proofs that we are all intuitive.

HR: You're reading my mind. That's exactly the insight that came to me spontaneously while I was giving that talk. Afterwards, I decided to investigate how this intuitive communication between people in the Dream Helper Ceremony operated. It led me to the discovery of what I call the "Intuitive Heart." It relates to the idea that when we care about someone, our heart "goes out" to that person. In other words, we form an intuitive, empathic connection. The secret of dreaming, I believe, is that it is an empathic process.

DNJ: It seems so obvious when you say it like that, that dreams are a form of empathy. Does that affect how we should see dreams, or interpret them?

HR: I think so. Rather than seeing dreams as containing hidden messages, see dreams as experiences of empathy. Then use empathy with the dream to reconnect with the experience of dreaming itself. I've been researching this process using a form of intuitive dream interpretation.

DNJ: What do you mean by "intuitive" dream interpretation? Doesn't all forms of dream interpretation employ intuition?

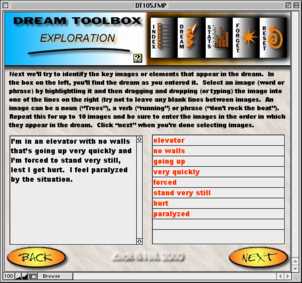

HR: In what you might call "analytic" dream interpretation, we look at the story line of the dream, or patterns, or symbols, or feelings. In other words, we begin by analyzing some feature of the dream by a standardized process to get a handle on the dream's meaning. In intuitive dream interpretation, we are looking for an immediate, holistic response to the dream. In the Bible, Joseph interpreted dreams and called it a gift from God. That suggests an intuitive response, direct from the unconscious. To explore this type of ability, I've tried having people get into a meditative state and hear the dream. Another approach is to read a dream to someone who is hypnotized. A really fun way to do it is to have people dance themselves dizzy, then respond to a dream--that works surprisingly well.

DNJ: I guess you help people get out of their minds, and then dream interpretation comes easier.

HR: A dream occurs in a special state of consciousness and is the best expression of itself. So what state of consciousness do we need to be in, in order to be able to directly appreciate the dream? That is the quest of intuitive dream interpretation.

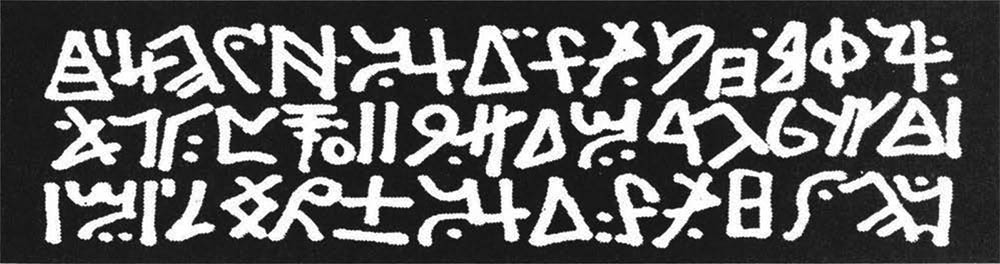

Most recently, I've explored something akin to dream divination as an approach to dream interpretation. Tarot readers, for example, will throw down cards and interpret a dream before they even know what it is. There's a big synchronicity element there, which of course pertains to intuition. The Mayans also do something similar, using a calendar divination to interpret your dream, again, before they even know what the dream is. These methods have something in common with the Dream Helper Ceremony, because in all cases, someone tries to help someone else by forming an intuitive empathy with that person's issue. So I created an experimental procedure I call Intuitive Heart™ Dream Story method. It goes like this:

Person A makes an intuitive heart connection with person B, who has a dream in mind. Person A allows a personal memory to spontaneously emerge in consciousness. Person A tells person B the story of that memory. Person A then begins to reflect upon that story as a teaching story: what does Person A have to learn from that story, what lesson does it contain. Afterwards, person B tells the dream and makes the connection with the story. The structure of this process grows directly out of the Dream Helper Ceremony. One person goes inside to get something personal, makes a lesson from it, and that lesson also feeds the other person. What makes it more interesting is that a dream itself is a story. A dream interpretation is a story about a story, and it is interesting to see how one person's personal story opens up another person's relationship to a dream. Here again we are seeing the community building aspect of dreams.

DNJ: You are like a walking dream encyclopedia, Henry! I admire the creativity and spirituality that you have evolved and introduced into scientific circles as well as among every night dreamers. I'd like to tell a brief story. When I first started stewarding Dream Network Journal, one day I stood with hands on hips staring at a huge pile of 'nuts and bolts' work that needed attending. I was feeling a little disenchanted -- like the individual who achieves enlightenment and/or experiences nirvana and is then told to 'chop wood and carry water.' Just then, I heard, from behind my left shoulder, a chorus singing a phrase from one of Paul Winter's albums: "And great is your reward in Heaven!" That's all it took to energize me for the work at hand and it has sustained me ever since! I sing it now to you. Can we look at the dream story from a broader perspective? Hopefully, you can weave a response around this series of related questions: What impact do you perceive the Dream movement is having, culturally.... especially in Western culture? Are we, in fact, helping to raise consciousness, to bring about the changes that are so evidently needed? What changes have you perceived over the past 30 years?

HR: I think the study of dreams introduces the transpersonal into the culture. Dreams have always expanded our understanding of reality by challenging our boundaries of the real, of the possible. One of the ways dream study impacts the culture, especially as we hear one another's dreams, is that we are put in touch with the inner poet who dreams. We hear our inner, subjective response to the outer world. That helps spiritualize our lives, which means in this context, to fight against the idea that we are just machines, that the universe is a mechanical process. Our dreams show us, and do so especially when dreamwork allows the people to hear one another's dreams, that we are spirit and are alive and well and paying attention.

The change I have seen, is that people are learning to feel more comfortable hearing one another's dreams. It used to be that if you told a dream in public, someone had to make a joke to relieve the tension introduced by that alternative reality. The dreamwork movement has been helping to socialize people to respond in a more constructive way to hearing a dream. That ability to listen and respond to a dream in an accepting, open, way creates a path for the dream consciousness to enter our culture in a more significant manner.