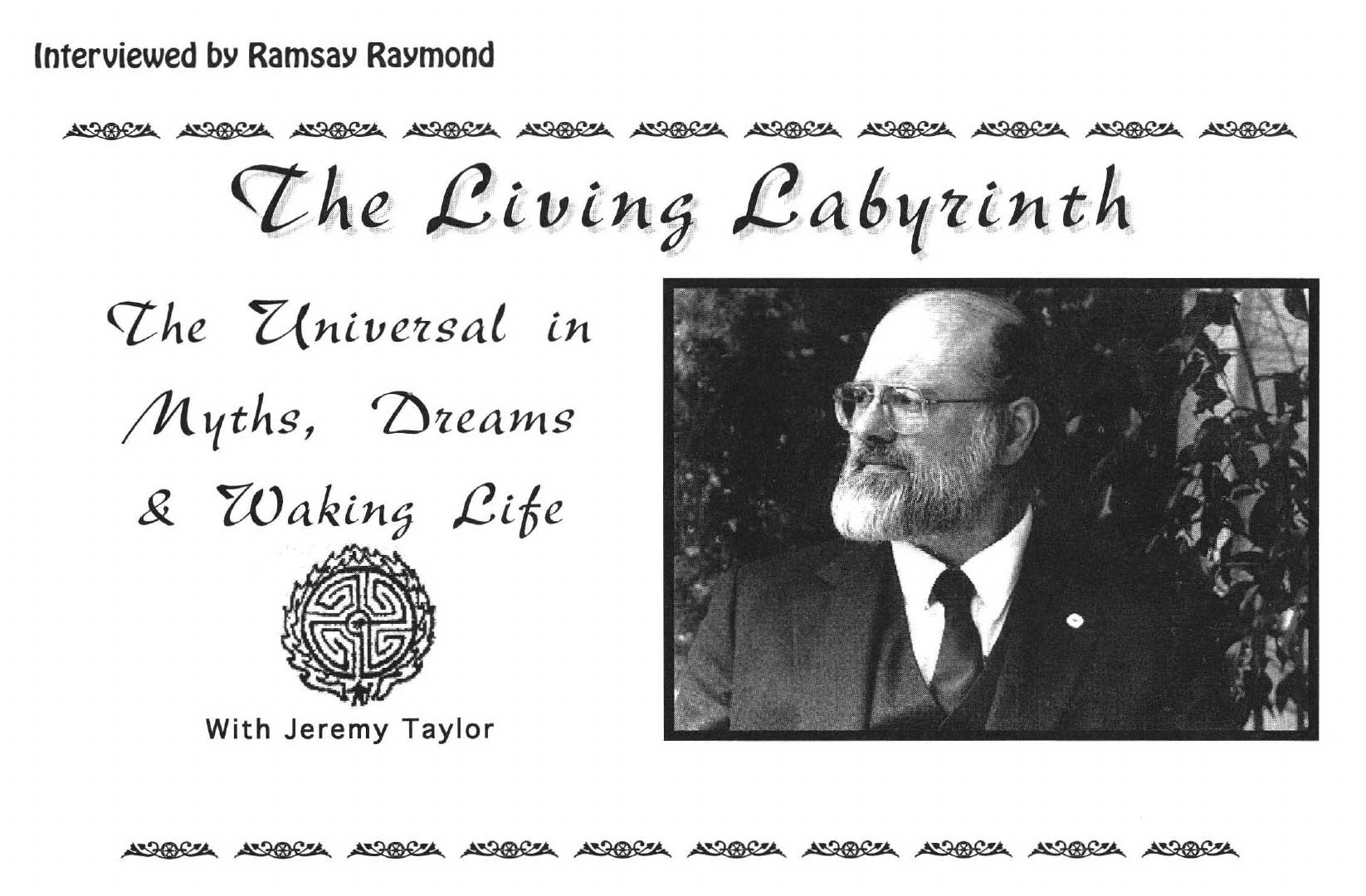

Jeremy Taylor was born in Newton, MA and raised in Buffalo, NY. He left home at age 15, going to the Virgin Islands where he learned scuba diving and cabinet making. For many years he was an avid motorcyclist. Jeremy enjoys writing poetry and drawing. He is a radical Unitarian Universalist minister and a community organizer with a deep faith and dedication to his ministry. His wife, Kathy, says that Jeremy is a 24 hour dreamworker. The Taylors live in San Rafael, CA with their daughter, Tristy, age 16. Jeremy is the author of Dreamwork, published by Paulist Press.

I talked with Jeremy in their home where his wife Kathy joined us. I find it delightful to be in their place. It is so cozy with little nooks and crannies filled with unusual objects collected from around the world. It contains so many treasured volumes that it looks rather like a sanctuary for books.

Jill: When did you first start out in dreams?

Jeremy: When Kathy and I were first together, some 27 years ago, we found it helpful and interesting to share our dreams both from a personal point of view-learning about sexism-and from a literary-esthetic point of view (both of us being literature majors). About seven years later, when I came out to California to finish up my alternate service as a conscientious objector, I was part of a project, the purpose of which was overcoming racism.

There was a problem in the project with disaffection among the volunteers. The director asked me if there was anything I could do and I put together a seminar, which backfired. The volunteers supported one another's disaffection. I said, "Let's not tell any more war stories. Let's not even talk about waking life. Let's just tell our dreams, especially those involving racism".

The results were stunning! There was an extraordinary change of tone, withdrawal of projection and the beginning of people starting to deal with one another at a much deeper level of intimacy and general concern. It was a transformative experience for all involved. Others in the program laughed at what we were doing, but the director said, "Look at the results".

That was the first time I let myself have that thought, "look at what we've accomplished here!". I said to myself if looking around blindly in our dreams, without the faintest idea of what we are doing, can do this and begin to impact the deep psychological sources of racism, what else can it do? That was 20 years ago and I have not looked back. In some sense I am still no closer to an answer to that question than when I started. Every time I think I'm getting to some kind of boundary: "Well, dreamwork can do this but it can't do that; I find that, in fact, it can do that.

Jill: I've discovered the boundaries always turn out to be personal, beliefs and fears.

Jeremy: Yes, exactly. I am still a community organizer. I see this dream business as important primarily for its collective significance. It's wonderful all of the personal and individual work that happens when people do dreams, but if that is all that it was about it would be interesting and I would undoubtedly still do it myself, but it would not be the center of my ministry.

That's the thing that separates my work from most of my colleagues who I see as stuck in the ghetto of the personal. I think that's a terrible mistake, but given the nature of our historical circumstances, it is certainly understandable.

Jill: When did you become a minister?

Jeremy: I have only been an ordained minister for nine years. In my denomination the only people who can ordain are the congregation. I taught dream classes at the Starr King Theological Seminary for 11 or 12 years prior to my ordination. The congregation in Berkeley wanted to acknowledge my ministry, legitimize it and honor it, so they ordained me. It was a "back door" way of being ordained and some of my colleagues are not real happy about that, but we get along and I'm in it for the long run.

Jill: So dreams have been one of your tools since you stumbled across it 20 years ago.

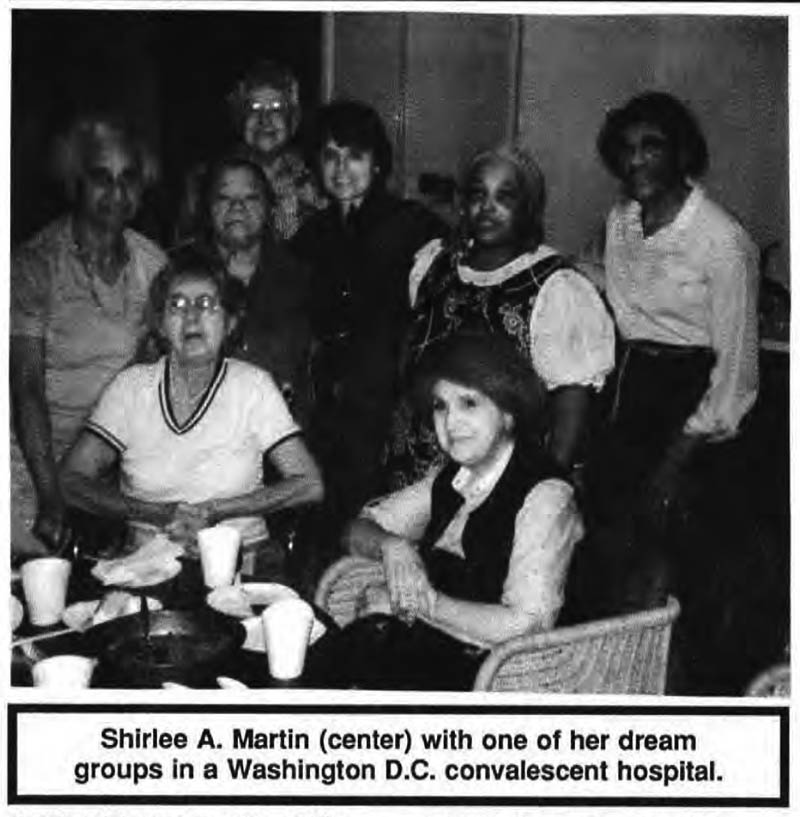

Jeremy: Yes, dreamwork is my primary tool. I've done it in churches, prisons, hospitals, residential treatment centers for adolescent schizophrenics, day care centers, and old folks' homes; you name it. Four or five years into the work I decided that if what I was coming to believe was true, that the dream was in fact universal, and cut across boundaries of age, race, sex and class, it behooved me to seek dramatically different venues for doing the work.

For example I was a HeadStart director for five years and introduced dreamwork into the HeadStart program early on. It even survived a couple of years after my departure. The transformative power of the work is what persuaded the staff. They discovered how much easier it was to teach when the kids were talking about their dreams. They decided, on the grounds of group dynamics alone that it was a good idea.

One of the most important kinds of dreamwork that needs to be done more is with the terminally ill and the aged. I'm doing more and more of that. It's very athletic and demanding work, but their dreams come in a last spurt. Their dreams tend to be poignant and meaningful and this group seems to be particularly ready to receive the gifts from their dreams.

The other kind of venue I've worked in is different cultures. I've done dream work in Canada, England and the Mediterranean cultures. And I've worked with people from many different cultures in this country. Different cultures have different areas of openness and repression. They therefore respond to dreams and dreamwork in different ways.

Dreams are a powerful transformative tool in any culture but it still depends on how the individual views the dream. I think it would be nice sometime to have an ASD conference in Australia since both Australia and New Zealand seem to be very open and receptive to transformation through dreamwork. It would also give us a chance to honor Ann Faraday, who currently lives in Australia, as one of the mothers of the present dream movement.

Jill: Where do you see the dream movement presently?

Jeremy: Northern California is the center of the global dream movement. It's not too surprising that the most evolved social structures are here. There's more of a tendency here for dreamworkers to be mutually supportive and operate as a community and less of a traditional competitive business relationship. I see community service and planetary concern as an essential part of being a dreamworker. Self promotion without an element of public service is venal and stupid.

Jill: Do you have any suggestions for dreamworkers in promoting their work?

Jeremy: First you have to make a concerted effort. Secondly, cultivate cultural and institutional connections. Ultimately questions of self promotion boil down to tone setting and self image. Knowing that you can do good dreamwork and help people see the meaning of their life will produce a kind of centeredness and clarity that will attract more people to you than four color posters. It is not a matter of sophistication of promotional technique. It is a question of knowing the depth and value of the work that you are doing.

You have to be ready to do dreamwork or presentations whenever the opportunity arises, whether with an individual or a group, whether you get paid or not. For 15 years I worked at other jobs, but always bringing dreamwork into whatever I did.

Kathy: People don't understand how hard Jeremy has worked but I've witnessed it from the beginning. He has 24-hours-a-day dedication, doing up to four groups a day and leads workshops almost every weekend. He gives away 10 times as much as anyone else. For the past five years he has been enormously successful, but the previous 15 were give and take.

Jeremy: One of my problems is that I love the work, so while I'm in the middle of it I do not realize how much energy it has taken. My immediate experience is of being more energized. However, when it ends I crash and realize how little I have left. h has taken 20 years for me to get a handle on how to stay balanced.

Jill: I was going to ask you what was hardest about being a dreamworker and that's probably it?

Jeremy: Well, no. For me the hardest thing about being a dreamworker is internalizing other people's pain. It's a particular problem with the style of dreamwork that I do, which is taking each person's dream and making it mine.

Kathy: When you worked at San Quentin Prison and with Satanic cultists, that was the hardest.

Jeremy: Yes, and also when I worked with AIDS patients. Part of the irony, from my point of view, is that you're not doing good work unless you're willing to be infected with their misery. The upside is that you get infected with people's creative energies, love and transformation as well.

Jill: What has brought you the greatest satisfaction in your work?

Jeremy: At the moment the most satisfying thing is to have my work affirmed through having my book, Dreamwork, published in German even though they never met me. And of course when I'm doing dreamwork and someone has an "Aha!" of recognition or insight, that moment is the most satisfying thing. But I suppose that the thing I am most pleased about is figuring out that the language of the dream is universal and that everyone is an expert, and finding ways to have people become conscious of that. I am most pleased at forging dreamwork, in the fire of experience, into a community organizing tool that wasn't there before.

Jill: And a lasting tool.

Jeremy: Yes.

Jill: What about dreamworkers and the issue of liability?

Jeremy: That's one reason I do this as a ministry. What transpires in the course of pastoral counseling is not subject to the same kinds of insane liability that medical model activities are. Personally I also prefer to work with a religious constituency because of the historical precedent for seeing dreams as communing with the Divine. This tends to make people open to the transformative power of dreams. What I do is not therapy. I offer spiritual direction.

The whole religion issue is complicated, but Kirby J. Hensley has done the legal work. You can get an ordination from the Universal Life Church* (or other mail order ordinations) by just sending in a small donation. And this ordination has held up in court. My work has shown me that dreamwork is essentially spiritual work. If you believe that in your heart, then Kirby's ordination will be of use. It's a matter of shifting your perception from what looks real to what is real. That is one of the things that dreams are always asking us to do.

Jill: Is ordination the only way that a dream worker can protect themselves from liability dangers?

Jeremy: From a legal point of view the best thing you can do is call it consultation. In California you can't call it therapy without a license. But different states have different laws. As a consultant, the liability issue has to do with fraud and you just have to be clear about what it is that you offer.

Jill: I cast myself in the role of an educator. If there's a complaint, it would be a matter of someone saying they didn't learn anything or it wasn't helpful. I teach an amazing amount of information and experiential exercizes, so I feel there's a minimal risk.

Jeremy: And if you run into really troubled people, you can tell them that what they're bringing you is beyond your ability and desire to deal with. Then offer them a list of people or organizations who might be able to help them. I keep a current referral list for that purpose. You can let your fear of liability paralyze you and not do work at all and I don't think that anyone is particularly well served by that. Risks are part of life.

Jill: What does it mean to be a professional dreamworker?

Jeremy: You don't get to be a professional just because people pay you money, nor by getting licensing and academic degrees. If you're going to use the name "professional" it seems to me you need to be engaged in some kind of social service. Being professional is a matter of the attitude you have toward your work. Are you approaching this work with a sense of spiritual purpose?

Dreamwork is not just psychological, but is psycho-spiritual.

Jill: Is this why you changed the character of the Marin Dream Institute?

Jeremy: Yes. Originally it was the Marin Dream Workshop. We put on two dream festivals in cooperation with the Bay Area Professional Dreamworkers Group. Then we came up with the idea of an institute designed to provide a program in dreamwork leading to certification. We held many meetings and worked on the project for a number of months before we came to the realization that this was not the proper format and gave people the wrong idea. It gave the impression that to become a professional dreamworker you take a training program and get a piece of paper that says you are certified to do dreamwork.

We recognized that offering "festivals" was more in keeping with the true nature of dreamwork. Dream festivals offer the opportunity for more dreamworkers and more members of the public to be involved. The framework is more open and flexible and does not make distinctions between presenters in terms of credentials or experience. The atmosphere is lighter and more fun. It's more of a community event than a school. Every festival is different, a whole new gestalt of individuals and energies. Rather than a fixed program of instruction, the festivals offer exposure to a wide variety of dreamworkers with whom one can study. If an individual wished to become a dreamworker, they would be responsible for creating their program and for determining their own readiness to work with groups or clients.

Jill: Besides festivals, what other future plans do you have?

Jeremy: I have a lot of things cooking. I'm three quarters through writing a book on archetypes entitled Universal Themes in Myth and Dreams. And I have a contract for a mass market book on intellectually responsible dreamwork. I have finished a science fiction novel on planetary survival and dreams. I have a second novel in outline form with a less overt dream focus. I enjoy writing fiction although I don't have much time for it. I'm working for Matthew Fox, a radical Dominican priest, who runs the Institute for Culture and Creation Spirituality in Oakland, CA. I offer several things there: courses on world mythology, pastoral counseling, Jungian psychology and dreamwork. I enjoy very much working with Matthew.

This summer Kathy and I are taking a group of people on a trip to some of the sacred places in Greece where we will explore Greek mythology and dreams. We will return from that trip on July 9.

Jill: You were a member of a Marin County dreamworker support group some 10 years ago called Coat of Many Colors. Because of that experience and other experiences since then, how do you see such groups relating to the dreamwork movement?

Jeremy: We heard about one another from mutual clients and decided it would be fun to get together. John Van Dam, Ken Keizer and I were the driving force behind the formation of the group. We met weekly in the morning where we supported one another professionally and shared dreams. Some of the other members were George McLaird, Bob Trowbridge, Bill Schutt, Jeremiah Abrams, Linda Purrington and Barbara Goodrich. Others came and went through the years. We put on two workshops during the time we were together.

This group and others like it can serve to increase cooperation and facilitate cross fertilization. We found it more than fun. It was tremendously supportive and useful. The first Marin Dream Workshop festival was very close to a reunion of the original "Coat" group. The dreamwork movement is a social movement building a society that nurtures diversity. In my view that is the only way worth going. Unless we devise ways of supporting one another the tremendous potential of this movement will be squandered. I hope that doesn't happen.

* Universal Life Church, Inc., 601 Third Street, Modesto, CA 95351.

The following dream is taken from Jeremy Taylor's Nurturing the Creative Impulse, Dream Tree Press, 1982. He cites one of his dreams as an example of humor and problem solving in dreams.

Some time ago I dreamed that everywhere I go in the course of my normal business I see a huge block of French cheese standing incongruously in the scene somewhere. I never see the cheese move, but wherever I go, there it is, and I have the feeling I am being "shadowed" by it. Just as I am waking up, I see it again. I ask myself, "What's that doing there?" and immediately an answer pops into my mind with embarrassing clarity.

On one level, there is a visual pun on the phrase "big cheese", a humorous reference to my mildly obsessive desires to be influential, famous and rich. I also realize with a flash of insight that it is a "French" cheese because, as with many varieties of French cheese, it is simply a matter of taste whether people think I have charm and robust character, or simply that I stink. There is a sense in which my big-cheese-ism causes me to project on others, and in that sense it is indeed a "block" to overcome and be transformed.