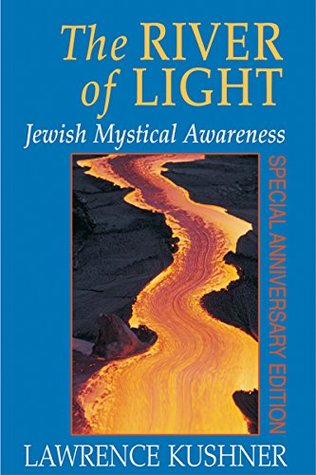

Even with its descriptive subtitle, Spirituality, Judaism, and the Evolution of Consciousness, Lawrence Kushner's book THE RIVER OF LIGHT would hardly find its way into the hands of someone looking for the latest good book on dreams. A friend recommended I read it because the first chapter was about dreaming. I found the whole book was. "The dreams we have dreamed are none other than the lives we live," Kushner writes in his simple, profoundly penetrating prose, "We made the dream. We wrote, are writing, and will rewrite again its lines. Shifting its selves and plots and scenery and sequences in accordance with our abilities to endure awareness."

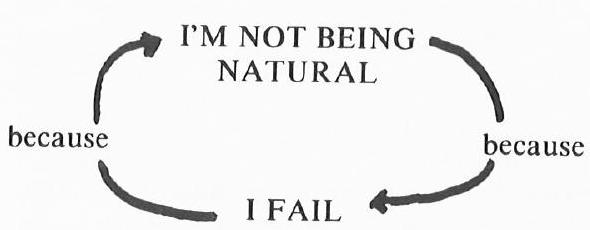

Our ability to endure awareness: that's it! We can only admit so much of reality into our conscious mind then the picture becomes too painfully at odds with the script that society or our parents or we ourselves have devised for us to survive by. That script is called deadness neurosis. It's our survival tactics that get in the way. The secret is that more than survival is possible. We can prevail, we can transform. We can become beings of light. Our dreams don't make sense to us because our lives make no sense. What comes up pure from within is distorted as it nears the surface of our consciousness.

"Unable to withstand the going up from our depths, enough to remain in its simple form, it cloaked itself in mystery, transformed intolerable desires into dense imagery and words, deleted the 'good parts', substituting them with parts that seemed 'good'. Now all we have left is the piously handed down scroll. filled with square black letters, the spaces between them, and of course, our own fragmented memories of a dream... Once a dream is told, it becomes something else. No sooner has it been recorded or told or even remembered then it ceases to be a dream. Now it is part of waking, it is torn from what shines beneath it and bore it, no longer part of the totality, only a story, perhaps. Waking consciousness closes out more than it lets in."

One way waking consciousness has of closing things out is to compartmentalize. We learn new ways of perception from working with dreams but don't apply these to our waking life, which is only a lived dream; or to films and literature, which are merely externalized dreams. Kushner is a rabbi, not a psychotherapist. He obtains his material from the source that is most familiar to him. "Not long ago," he writes, "we dreamt the Bible. From deep within our several and collective unconsciousness, we brought it forth. Twisted, convoluted, and mysterious. But nevertheless true... By reading holy literature as if it were a dream, we gain access to a primary mode of our collective unconsciousness." If the Bible is an ancient product of the dreams we are all still dreaming, though imperfectly aware of, then it follows that the techniques of dreamworkers can properly be applied to it to yield a blueprint of our own psyche and an understanding of the processes by which we undergo transformation and renewal. The Old Testament abounds with short, clipped and seemingly disconnected passages. "There isn't much left to work with " Kushner observes, "like with a dream."

The techniques Kushner employs are not unfamiliar. Yet he seems to draw them from a different, or perhaps earlier, tradition. For instance, here is how he presents what certain dreamworkers would call a "rewrite":

"This deliberate leaving of the text of the 'remembered dream', creating a story and returning to the next word, is called, in Hebrew, Midrash. Not the creation of a story from out of thin air, which is called 'fantasy'. Nor the elaboration of one word or event and returning to this same word or event, which is called 'commentary'. But the deliberate filling in of the gap between two words. Not to dissolve their individuality, but to fuse them into the even greater totality from which they have risen and of which they are only a part. This is called Midrash."

Kushner's aims, likewise, are as refreshingly stated as they are familiar:

"Health (to heal, to make whole) is the result of connecting the discordant and apparently unrelated pieces. And illness is pretending (or believing) that what is broken is really whole... Because we do not perceive our actions as responsible to previous events... our lives seem to be ruled by the caprice of distant, uncaring powers. Our joy is irrelevant. And our grief is unbearable. On the other hand, if we can create a story connecting one 'fragment' of our lives with another and thus join with Midrash-gossamer like webs those separate fragments of our existence, there is now a sentence where before there were only words. Meaning is literally in the connections. And meaninglessness obtains when the events in our lives seem to us unrelated, discordant, and fragmentary... If Scripture is like a dream, the Midrash is like therapy. It is the creative process whereby some of what is concealed is brought to the light of awareness... Unconscious thoughts, repressed and out of sight, exert more force than those that have risen to the surface. It is what we once saw, imagined, planned, and knew as a child but have now forgotten that can free us. Indeed it is from their hiddenness that they derive their immense power. The force of any secret to control human transactions is well known."

The River of Light abounds with the simplicity and insight that comes from working with dreams. To quote again from the book:

"By the time you're old enough to do what you've been waiting to be old enough to do, it has all changed into a world that you did not make or want... Ultimately, all we seek to learn is what we as children once knew. All genuine learning is this the self's disclosure to itself. How odd and yet how universal the misconception, on the part of all who would learn, that the knowledge they seek is outside them ... Go down through your layers, through your childhood and your dreams... For the layers run back through time but also run all the way down to the source..."

How beautifully Kushner writes and how impossible to sum up his book except in his own words.

"The one who pays attention to the dreams, draws on them, and lives them out is blessed, even as the one who dreams is also dreamt. We each take our turn at living out the dream. Like some ageless wave, Scripture flows through us ... The Bible's image for the resolution of all paradox is the coming of the Messiah. The final transformation of consciousness itself ... The coming of the Messiah does not depend upon anything supernatural, but rather upon human growth and self-transformation... The world will only be transformed... when people realize that the Messiah is not someone wholly other than themselves. Knowledge of the self at the deepest level is, simultaneously, knowledge of God."

When we work with our dreams or the dreams of others we are not dealing with anything different than the writers of the Old Testament dealt with. It is perhaps a reflection of our diminution of consciousness more than anything else that our own tradition appears as mysterious and impenetrable to us as the dreams we dream. Because of the state of mind we have fallen into these traditions must be worked with just as we work with dreams. "We are not simply custodians of a tradition", Kushner writes, "not just keepers of a museum. Our goal is also to break it open. Set it free." In this task Lawrence Kushner has succeeded remarkably well. The River of Light belongs on the bookshelf of anyone interested in dreams and in personal transformation.