I got this email from Chris Hudson, a former editor and publisher of Dream Network who now lives in Bellingham, Washington:

"I found a tiny pink orchid on my walk through the forest today. About 2 inches high. Someone I met called it a Calypso."

I clicked on the digital image he sent. From across the Pacific Ocean, a delicate little wildflower from Washington State appeared on my computer screen here in Taiwan. As I studied it, my computer rang. It was Chris calling on Skype. Because I used to know about orchids a long time ago, he hoped I might help him further identify the flower. As we talked, I googled and came up with a picture of Calypso bulbosa on lensjoy.com, the website of a nature photographer. I couldn't make a positive match between the two pictures.

A few minutes after we signed off, a second e-mail arrived from Chris. He said his orchid was Calypso bulbosa and provided the link he'd used to make the identification. He also attached a better photo of his flower. This picture did resemble the flower I'd seen on the internet. I clicked on the site he sent. It turned out to be the same one I'd come up with. Chris's new photo matched. The mystery was solved. Just to be sure, I clicked around various botanical sites. Sure enough, his flower was Calypso bulbosa (L.) Ames, the fairy slipper orchid. Very closely related to Cypripedium, the lady slipper orchid, Calypso is a genus with only one species, palearctic in distribution. The same little orchid Chris found in the woods of Washington State is reported to extend all the way south to Arizona in the mountains of the western United States. It surprised me to find that such a widespread orchid had been put on a list of plants facing the danger of global extinction.

The problem is that orchid enthusiasts dig the little plants up from the forest and take them home to their garden, where they usually die. In fact, there is a growing illegal international trade in the orchid, even though this is a species that generally dies if dug up from the forest floor and transplanted elsewhere. The little orchid depends for its survival on a relationship it has with certain fungi in the soil of the old growth forest. Without the forest, it cannot survive. It doesn't exist as a thing alone, the orchid "plant" that we see, but like the alga and the fungus that together make up a lichen, it is an organism in partnership with another. To rip it apart from its other half and take it out of the forest is to kill it.

Here is a treasure of a species, widespread around the world in the northern latitudes. It's well adjusted to its environment. All it requires is to be left in contact with its hidden partner.

Everything else it can do on its own. It has what it needs in its underground connection that unites it to the forest all around and enables it to draw life out of thin air.

Like this little orchid, we too exist in relationship to something unseen and that something of ours also sustains us and unites us in the most amazing fashion with what's all around. We have our underground connection, our hidden partner, and can draw from that relationship what we need to survive. Unlike the orchid's partner, though, ours is not so easily named - although men down through the ages have never tired of giving it names. To this day, they fight and slaughter one another over these names.

Not only are we at a loss to name our intangible and transcendent counterpart but, if the truth be told, we have no way of even conceiving what it is. The mycelia of a fungus can be viewed under a microscope and identified down to species, but we have no instrument to view what some belief systems call God Almighty, and others The Creative Unconscious. Emerson had his Oversoul; Burke his Cosmic Consciousness. Whether it's Enlightenment, The Tao, Buddha Nature, Jehovah or Allah - if we call it Shiva or Vishnu - one thing is certain: there are almost as many concepts of what it is as there are individuals who have directly experienced it. The Buddhist notion of Emptiness is particularly apt because it acknowledges openly the truth found in the root core of every great tradition - this that we are linked to on the inside cannot be grasped by the conceptualizing mind. It pours forth of its own accord - an instant can be enough to change a life, or the course of a civilization. About it we know not how, why or what. But through it we are made to know ourselves and everything else in a truer way.

Just as anyone can tell a prettily flowering and living fairy slipper plant from a wilting and dead one-when that which we are connected with courses freely through us everyone can see the deep human joy in our shining face and happy, helpful manner. Everywhere we walk, things bloom-wounds are healed, lives are mended. A blossoming and living Prophet with such characteristics developed to a supremely higher and more exquisite degree than many of us will likely see in our lifetime - gave rise to each of the great belief systems. They all started at this point of immense truth.

And yet something clearly went wrong as the wisdom teachings of these great masters made their way down through the millennia to us. They started out being based on direct contact with the other half. Then they passed through generation after generation of individuals who twisted this into ideology. It all came out on this end as systems of belief in things that are supernatural and can't be proven. Each tradition started out celebrating a connection that is real and that can be directly experienced but over time each came to be about a body of beliefs that can't be experienced and that isn't real.

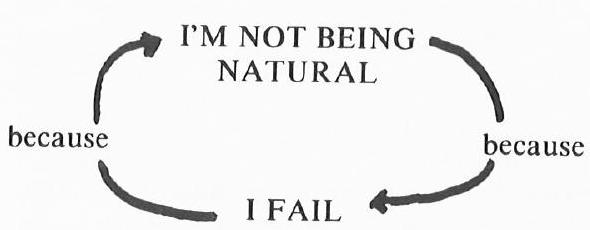

This would be fine and well, except that we are a species like the fairy slipper in this one respect: We don't survive being transplanted into situations that do not afford authentic connection with our other half. Dogma, brainwashing and acquired belief systems don't do the trick. You can see in the West, in Islam, in China-everywhere-without the real connection, we are not just incomplete; we are inhuman.

If I could sum up in a few words what I think Montague Ullman's greatest contribution has been, it's that he provided us a way to connect with what's most real in ourselves just by using our simple everyday dreams. His way of working with dreams differs from so many others in that it bypasses all the dogmas and belief systems-religious, professional and metaphysical-that in today's world tend to get in the way of truth perhaps more often than they lead to it.