When The Red Book of Carl Gustav Jung was published, it caused an immense stir, offering readers a plethora of new mysteries and depth psychology insights. I cannot predict that this interpretation will set so large a wave of interest in motion, but it may. READING THE RED BOOK certainly deserves attention. It is a work of wealth in itself. And you may find it of interest that the author confesses not to be a Jungian and yet he uses Jung’s often idiosyncratic spiritual quest—for soul, Self and the God-yet-to-come—to confront and challenge the materialist psychology dominating our materialistic society’s science of mind and soul.

From the onset, Sanford Drob is clear about what he has done and how he has done it. Beginning at the Introduction, it is worth listening into the author as he explains his intention. Drob’s first paragraph is this: “Jung held that dreams are challenges to the assumptions and complacency of the ego, compensation for one-sided conscious attitudes, or messages from the unconscious that prompt us to question the value and direction of our current mode of thinking, feeling and living. By this defi nition, Jung’s The Red Book...is akin to a dream... Like many dreams the dream that is The Red Book is at once magnificent and grotesque.”

A page later, the author sets before us the major points of his investigation: “Although I have endeavored to be balanced and as comprehensive as possible... I have become convinced that while The Red Book narrative centers around Jung’s’ soul-finding journey, its greatest value may be its ideas on such themes as God, humanity, madness, chaos, death, science, reason, knowledge, logic, and evil.”

Shortly thereafter, Drob introduces us to a confession, his method, and his intention. He continues: “I am not a Jungian. While I believe that my treatment of The Red Book is a sympathetic one, I do not hesitate to raise questions about Jung’s approach to various issues and his suggestion that spiritual wisdom and enlightenment must involve an inner, solitary journey. In many instances, without providing anything resembling an answer, I raise questions that the reader will want to consider for him or herself.”

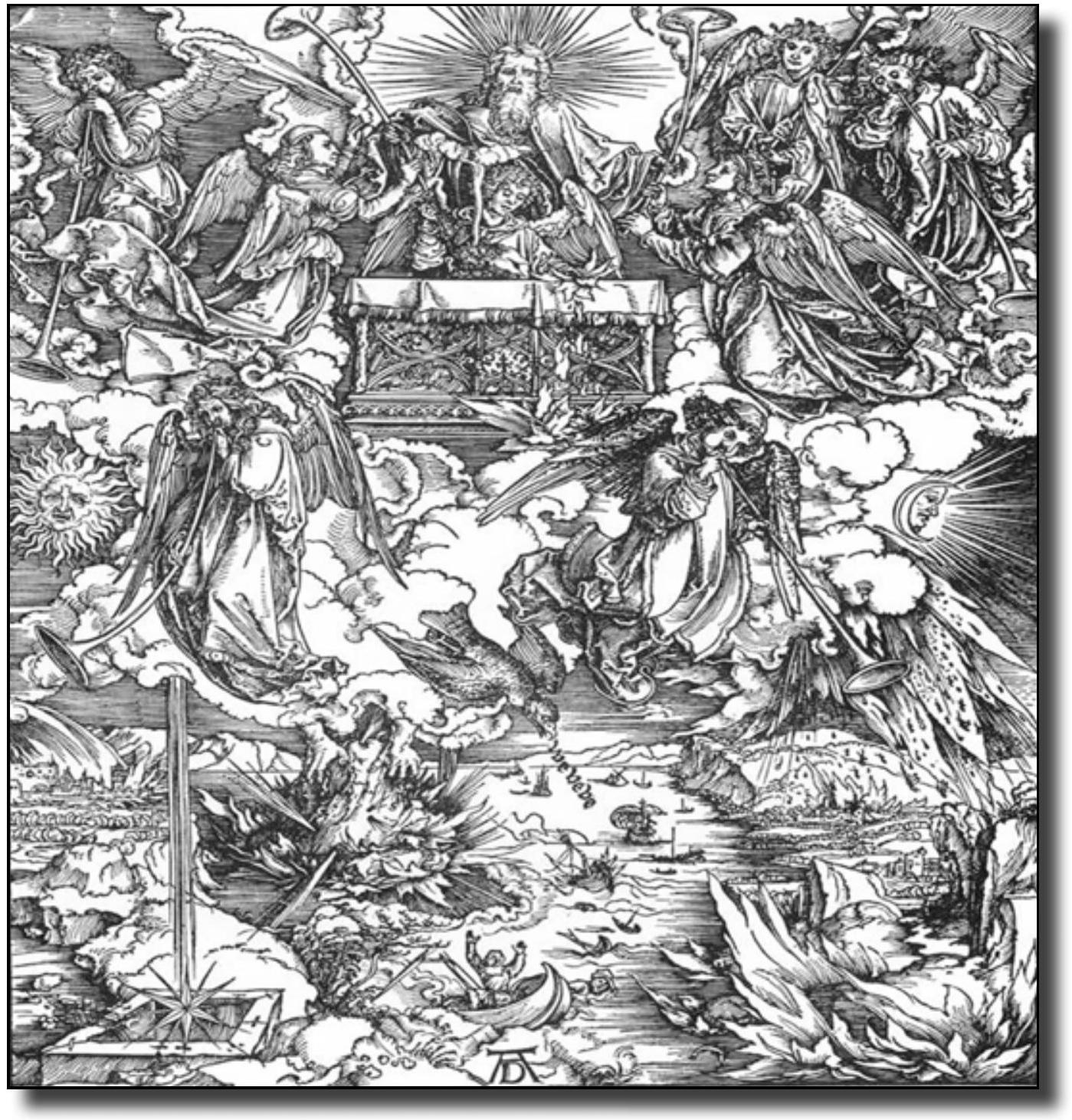

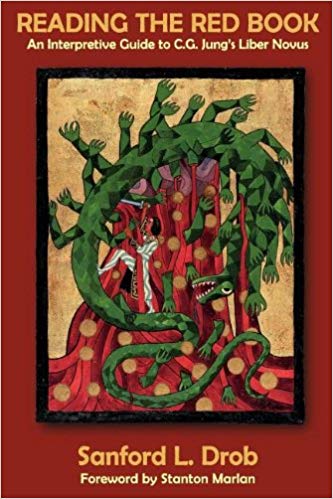

Drob concludes his informative Introduction with the following lines: “The immense size and weight of the facile edition, along with the haunting beauty and mystery of its illustrations leads one to approach Jung’s Red Book with a certain caution—it is hardly the sort of work that one curls up with in bed… and yet it is a work that, above all else, must be read; read, and then studied and reflected upon… In the present work, I propose to read The Red Book, and, in the course of this reading, wrestle with the questions it asks, _on the hope of experiencing something new, seeing life from a new perspective and perhaps being personally transformed in the process.” _

Sanford Drob is thorough in his investigative exploration of The Red Book’s Psyche Odyssey of CG Jung: an interior journey, an intellectual, emotional, spiritual going down into the depths—even Jung’s descent into personal hell, madness, chaos—to seek the alchemic matrix that brews the dynamics of individuation, the nexus of soul and self, and to search out the Unknown God who addresses emergent identity through the individuation process. One major result of this Odyssey is what Dr. Drob comes to refer to as “dream theology,” rendered out of The Red Book journey as dream... a dream of human psychology, which came to provide fertile ground for Jung’s psychology of dreams and dreaming.

Drob is also thorough in his routing back over Jung’s dreamlike rite of passage. Unfortunately, I cannot be so as a reviewer and must yield to the limitations of my spatial condition. Let me but cite several passages from the cornucopia of READING THE RED BOOK.

P.3: “Jung’s goal in The Red Book was to encourage others to discover their own soul and assume responsibility for their own lives.”

P.5: “Jung’s discussion of the spirit of the depths raises the question of whether there is...a form of gnosis that is not conditioned by time and place... It is the quest for such a trans-temporal, trans-cultural... understanding that fueled Jung’s early interest in mythology and conditioned his inquiries into the archetypes of the collective unconscious.”

P.6: “For Jung, the supreme meaning, which gives rise to the image of the God-yet-to-come, is the melding together of meaning and absurdity, sense and nonsense.”

P.22: “Jung asserts that meaninglessness and chaos is the ‘other half of the world,’ and no one can be complete or have a full understanding of the world without embracing its chaotic and meaningless elements.”

P.23: “The descent into chaos is perilous, but it also yields great reward.” (Jung) ‘If we open up to chaos, magic also arises .’”

P.29: “In Rudolph Otto’s terms, Jung seeks a numinous experience, an experience of the mysterium, that fearful yet fascinating and aweinspiring rapture that lifts one from the despair of the everyday and allows one to experience self and the world as bathed in the darkness of terror and/or the light of wonder, awe, and spiritual affirmation.”

P.260: “The Red Book has many characteristics that are typically associated with dreams: it is filled with strange, haunting and at times frightening images; its narrative is surreal and, most importantly, it arrives into our awareness in a manner that is completely discontinuous and disruptive of our business...as usual”

In summary: the individuation process, with connectives between soul, Self and an emergent God-image and in its dream-actuals and dreamlike episodes, disrupts established patterns of identity for the coming into being of mature identities, through dialectic developments and revelatory dialogues. The dream of The Red Book parents the work of depth psychology; out of the depths emerge contours of a dream theology. ∞