“Nothing happens unless first a dream.” - Carl Sandburg

I would like to talk to you about The World Dreams Peace Bridge, my current dreaming project. In order to do so it is necessary to first give you a little background about myself and about the fairly unique dreamwork process in which I have involved myself over the past thirty years or so.

Some History

I was fortunate that fairly early in my career in that I was asked to direct a small, non-profit organization in Virginia Beach, Virginia, called Poseidia Institute. At that time, the focus of research was on the intuitive process — what made people able to do such things as accurate psychic readings(?), for example. What made it possible for ‘healers’ to ‘cure’ and ‘telepaths’ to give information for someone halfway around the world?

Because these questions were primary to my own research as well, it quickly became clear to me that dreams — whatever else they may be — are the one altered state of consciousness we all share. Therefore, talking to people about dreaming might reduce the general awe in which psychics and psychic phenomena were held, that is when they were not being denied or ridiculed.

So I began with the premise that we are all psychic, that being psychic is our nature. It wasn’t long before the necessity to examine the nature of time and space became important to me as well, since the psychics I knew often talked about alternate realities, or other areas of time and space.

These were interesting times in the field of dreams, during the 1970s. John Herbert, Richard Wilkerson and others summed some of that history up in articles in the last issue of Dream Network.

On the East Coast, Dr. Henry Reed was publishing his Sundance Community Dream Journal for the Association for Research and Enlightenment (ARE). This journal served the function of bringing dreamers into dialogue. So popular was this quarterly journal that, when the ARE stopped its production, a New Yorker by the name of Bill Stimson decided that something needed to be done to keep the grassroots dream community going. He was so convinced, that he started a small publication of his own, the Dream Network Bulletin, which was an immediate precursor of the Dream Network you now hold in your hand.

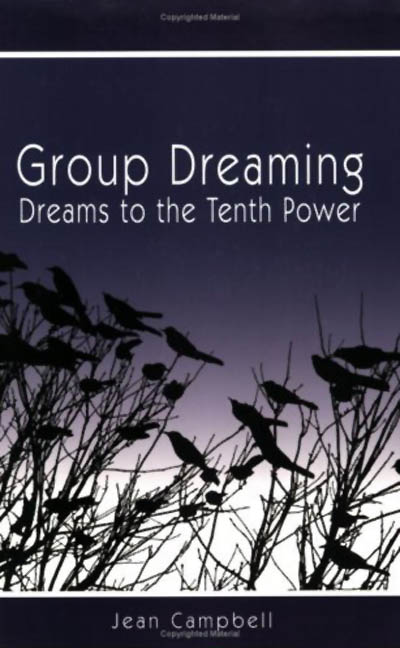

The staff of Posiedia Institute was involved in these events, with other editors of the DNB, Suzanne Keyes, and Linda Magallón. We were all volunteers in a project we called ‘Dreams to the Tenth Power’, a group dreaming experiment.

At the same time Henry was publishing the Sundance Community Dream Journal, he was also conducting his Dream Helper experiments, a process he had devised for getting people incubate dreams to help another dreamer.

In conversation one day, Henry and I decided it might be interesting to see if dream helpers could work with someone they’d never met, or met only briefly. So it was determined that the next person who filled out an application for a psychic reading from one of Poseidia’s staff of very competent psychics would be, if they were willing, the target for a Dream Helper experiment.

The majority of people coming to Poseidia for readings at that time were there for medical assistance, often referred by their doctor or therapist. So when the next application arrived, we invited the young woman to participate in this joint ARE/Poseidia Institute experiment.

What occurred to me the next morning, when the ‘dream helpers’ met to report their dreams—myself among them—was that not only had several members of the group accurately targeted the young woman’s illness, but the dreamers actually appeared to have shared dreams.

This subject of sharing dreams fascinated me so much that I decided to devise some sort of experiment to see if people could share dreams, possibly even lucid dreams, on a planned basis. This was the beginning of a set of experiments which took place over several years. The results of these experiments more than convinced me that spontaneous mutual dreaming is fairly common, though not so commonly reported; I was also convinced that skills such as mutual, and even mutual lucid, dreaming can be developed.

It was out of this background then that I returned in 1996 to The Association for the Study of Dreams. As one of ASD’s earliest members, I had presented at the second ASD conference in Charlottesville, Virginia, but then left dreamwork behind for doctoral work at American University, and later for work as a senior Science Fiction/ Fantasy editor.

We’ll Cross That Bridge When We Come To It

So how does all of that bring us to the World Dreams Peace Bridge?

The period between 1985 and 1995 was very important to the study of dreams. In California, Linda Magallón continued the study of mutual and group dreams, finally resulting in her book, Mutual Dreaming, published by Simon & Schuster in 1997. Interest in dream lucidity continued to grow, supported by activities like Ruth Sacksteder’s Lucid Dream Exchange.

Although there continued to be an interest in both interpretive dreamwork and theoretical dream research, dreamers were also becoming interested in such things as Dr. Stanley Krippner’s ongoing research into Shamanic dream practices around the world, and the work of Australian author, Robert Moss. These researchers and others were talking about the important role dreaming has played in world cultures, apart from the more scientific models of Western culture.

I have often told the story of sitting at a table overlooking the ocean on the terrace of the beautiful University of California Santa Cruz campus, with a group of some of the top experts on dream lucidity. Someone asked how people had first become lucid. One man responded, holding up his hands, “I looked at my hands.” One by one, around the table, people grinned and held their hands in front of their faces in silent homage to Carlos Castaneda who, even if he made it all up, introduced an entire generation of dreamers to lucidity through The Teachings of Don Juan.

During the decade in which I was away from dreamwork, more dreamers had become conversant with theories of time and space presented first by Albert Einstein, followed by an entire group of nuclear physicists and popularized by writers such as Gary Zukov, Michael Talbot, and Fred Alan Wolf. Now it was not so unusual as it had once been for dreamers to believe that possibly consciousness—particularly dreaming consciousness—could extend beyond the boundaries of linear time and cross the boundaries of space.

“In the days following 9/11, it seemed to me that maybe it was time for a practical experiment. If it were true that we are dreaming the world, and if it were true that dreamers all over the world could come out of isolation via the internet, then perhaps we should join together to explore the possibility of dreaming the world into peace.”

Possibly the single most important development of the decade was the Internet, where almost as soon as longdistance communication was possible, dreamworkers like the Rev. Jeremy Taylor, John Herbert, Jayne Gackenbach, and Richard Wilkerson were communicating globally with dreamers around the world and constructing Internet dream resources which far outshone anything available to dreamers prior to that time.

When I returned to ASD in 1996, almost the first thing I did was volunteer to moderate the Online Bulletin Board at http://www.asdreams.org. I was fascinated by the potential of the Internet to link dreamers with one another and to provide instant communication. Whereas before, when the ‘Dreams to the Tenth Power’ research was going on, weeks of sending dream accounts and responses through the mail were discouraging to dreamers. Now communication was instantaneous, free... with the click of a key.

As soon as I began to moderate the Online Bulletin Board, I noticed one less-than-surprising thing: a majority of the questions—from kids writing school papers, from adults with sleep disorders, from dreamers all over the globe—focused on subjects which, heretofore, had been classified under ‘paranormal’ dreaming or ‘anomalous’ dreams. There were questions about out-of-body experiences, about dream telepathy, about mutual dreams and experiences of sleep paralysis. It seemed that this type of dreaming, far from being paranormal, was — if we were to believe the people who came to the Bulletin Board — very normal indeed.

The visitors to the Bulletin Board, some of whom became so regular that we began to call them Boarders, carried on the practice of grassroots dreamwork which began in the seventies. Even though dream interpretation is not done on the Bulletin Board, wideranging questions about dreaming and dreamwork are discussed, with equal participation from therapists, sleep and dream researchers, artists as well as from dreamers themselves.

In the two years after I began moderating the Bulletin Board, Ed Kellogg developed the Paranormal Dreaming Forum on the ASD site, and we began also to create ASD Member Pages, which allowed for members to put up a page online, introducing themselves and their work. It was not long until I conceived a plan for bringing International members even closer, through the medium of the Internet. In 1998, I invited ASD members around the world to participate in the construction of the Online Guide to International Dream Work. This project not only provided a stunning array of multi-language pages for the ASD web site, but it also built a feeling of camaraderie among the ASD members working on the project, even though they lived in Greece, Russia, Switzerland, Australia and many places in between.

The Effects of 9/11

Given my sensitivity to the issues of interest to the online dream community, it wasn’t much of a stretch for me, when I saw the televised report of the second plane flying into the Twin Towers on the morning of September 11, 2001, to go to the computer and invite people to post their dreams and feelings to the Bulletin Board. I saw the number of precognitive dream reports without surprise and before long I was writing an article called “Dealing With Precognitive Dreamer Guilt,” http://dreamtalk.hypermart.net/campbell/dreamer_guilt.htm, which Richard Wilkerson generously published in his online magazine Electric Dreams. I was touched by the outpouring of sympathy and understanding, which came to the U.S. from dreamers around the globe.

Then, as the bombs began dropping in Afghanistan, two of my lifelong interests came together with a very loud click. I have been a pacifist ever since, as a graduate student in the 1960s, I did Conscientious Objector counseling for the American Friends Service Committee.

I remembered the plenary speech Dr. Stephen Aizenstat, director of Pacifica Graduate Institute, made at the 1999 ASD Conference in Santa Cruz: ‘Dreaming the World.’ That lecture caught my attention because Aizenstat was saying what I had believed for years: that people, and all sentient beings, are dreaming the world into existence, all the time.

This is not a new idea, having been the foundation for Aboriginal Australian culture for thousands of years, as well as fundamental to other indigenous cultures. Numerous psychics, such as Edgar Cayce and Jane Roberts, have said the same thing.

In the days following 9/11, it seemed to me that maybe it was time for a practical experiment. If it were true that we are dreaming the world, and if it were true that dreamers all over the world could come out of isolation via the internet, then perhaps we should join together to explore the possibility of dreaming the world into peace.

The World Dreams Peace Bridge

In October of 2001, I sent an e-mail to approximately one hundred people: friends, family, those ASD members who had worked on the Online Guide to International Dream Work, inviting them to join me in a discussion group, which I later labeled the first-ever longterm group journaling experiment. There was something that had struck me in my own briefly precognitive dream on the morning of 9/11. In that dream, I was standing in the control tower of an airport, watching as an air traffic control person dealt with an obvious emergency.

What struck me about the dream was that, although I was in the control tower, I was only an observer. My dream reminded me that I had the ability to respond, a response-ability to be in control, as we all do if we believe that we are dreaming the world.

In the last issue of Dream Network, Richard Wilkerson labeled this emerging attitude as Dream Activism. In fact, there are other groups now following the model of the World Dreams Peace Bridge, and there are a growing number of dream activists. Is this a new concept? Not entirely. During the time between the emergence of ‘grass roots’ dreamwork and today, many dreamers have recognized that — from a certain position in the dream, often a lucid dream, and sometimes a group or mutual dream — it is possible to act consciously from the dream state, to communicate with others and to participate in creating the magic of reality.

The World Dreams Peace Bridge, which maintains an active membership of around fifty people, is composed of dreamers from around the world: Australia, Japan, the Netherlands, Austria, New Zealand, the U.S. and many other places. In its waking form, as a discussion group, the Peace Bridge operates as a support system for dreamers. New ideas are explored; dreams are told; because of its international membership, news is often reported from one country or another before it is picked up by the press.

At the dreaming level, the World Dreams Peace Bridge has acted as a catalyst for creativity. One example of this is the Peace Train Project, which has grown from a dream Jeremy Seligson dreamed in Korea in August 2002.

In the dream, Jeremy was riding with a group of people on a train across the country. The train, which bore a banner calling it the ‘Peace Train,’ ended up at a platform on which President Gore stood.

From the dream, when he first recounted it, Jeremy began to muse. What would happen if people all over the world began to create peace trains? What would happen if children were asked to create peace trains? What would peace trains carry?

Other members of the group began to get enthused and now—less than a year later—Peace Train projects and Peace Train workshops have been held or are planned for Korea, Australia, India, Turkey and the United States. UNESCO has praised the Peace Train Project. Jeremy has created a Peace Train song and is working on a video. There will be a Peace Train workshop at the ASD Conference in Berkeley in June. And the Peace Train Project has brought more dreamers to the Peace Bridge.

By the fall of 2002, the World Dreams Peace Bridge had become so active that we needed to create a web site. With the work of webmistress, Liz Diaz—who had already designed a beautiful World Dreams logo—http://www.worlddreamspeacebridge.org was created. The site, among other things, now houses a marvelous collection of art, which has grown out of the dreams of various peace dreamers.

Most recently, in the time just preceding massive world-wide peace demonstrations against U.S. attempts to convince the United Nations to approve war against Iraq, members of the World Dreams Peace Bridge sponsored a Peaceful Solutions Dream In, inviting not just members of the Peace Bridge but dreamers everywhere to join us in attempting to dream up peaceful solutions to the world’s conflicts.

In my own estimation, these are good questions for all dreamers to consider, not just dream activists. In the work I was doing at Poseidia Institute in the 1970s, I was often told that I was ahead of my time. Recently, when I helped to facilitate ASD’s first PsiberDreaming Online Conference, an online psi event that had participants asking for more, I was told that my first book on dreams, Dreams Beyond Dreaming, published in 1980, had withstood the test of time. But, for myself, I have seen Dream Activism as a natural development, an outgrowth of believing that dreams might predict the future or support such things as lucid/mutual communication.

Much has happened in the past thirty years to convince Western dreamers that we might be creating the world (or many worlds) through our dreams. Dream Activism, or projects like those of The World Dreams Peace Bridge, are no more than our attempt to become increasingly more conscious of what we already know to be possible. ℘