Stephen Aizenstat, Ph.D. is the founding president of Pacifica Graduate Institute, a private graduate school offering masters and doctoral programs in psychology, mythological studies, and the humanities. Dr. Aizenstat is a Clinical Psychologist, a Marriage and Family Therapist, and the creator of Dream Tending, which is a method of working with the figures and landscapes of dreams as “living images.” Dr. Aizenstat regularly conducts Dream Tending workshops; a calendar of upcoming events can be accessed at dreamtending.com. He also has a DVD on Dream Tending produced by Bison Films and an audio CD series on Dream Tending available through Sounds True. His book, Dream Tending, will soon be released.

Jeanne: When I watch you dream tending, what fascinates me most is how you shape-shift; the manner in which you physically change your physical being as you listen to the dream. I have witnessed you seeing the image, sometimes when it is not even in the narrative of the dream. So, if you could speak to that magical ability, I think it would serve anyone attempting to work with dreams.

Steve: Not magical, but imaginal. When I develop an image-centered relationship with the figures, by that I mean entering their world on their terms, images come to life, present themselves, say, “Here we are.” On the other hand, when or if we meet the dream for the purposes of interpreting or analyzing, then we’re going to bring our rational mind only into relationship with the material or content of the dream. At that moment, the visitation is lost, the actuality of its presence disappears. To witness the activity of a living image is a very different mode of perceiving and therefore a quality of relationship is needed. The “trick” is to meet the dream in the way of the dream. When I bring a dream-like consciousness to the dream then one thing happens, dreams come alive; and if I bring a rational, analytical mind for the purposes of interpreting the dream, then something else altogether takes place, dreams become static. It’s not that interpretation or analysis is bad, it’s just that my preference is to first let the dream come forward to show itself as its Self, as an embodied enactment; then, secondly, to bring my capacity for insight or analysis. I think that is what you are most likely noticing. It really is a different mode all together. It’s a mode of perception that is anchored in an imaginal consciousness rather than an exclusively logical, scientific mind.

Jeanne: How do you teach that or suggest that people wishing to get there begin the process?

Steve: There are four core skills that I suggest experimenting with. One is curiosity. When we get curious, we get interested. Rather than jumping so quickly to what we think the dream means, we get curious and follow the activity of the images and the figures of the dream. Curiosity takes us to a very different place altogether. The second, along with curiosity, is a way of listening. One way of listening is to listen for the purposes of offering an answer. So, we’re already rehearsing what the answer or the response will be before we have even listened fully to what is being presented. When tending dreams, it’s a question of taking a deep breath, getting anchored, and becoming receptive and responsive: listening first and allowing the conversation to emerge out of the silence, rather than using our active mind to fill the space. Responsive listening is the second skill. The third is to really pay attention to detail or particularity. Rather than seeing each image as the same— for example, the elephant, or even the house as all being of one kind— noticing how each image comes with its particular distinction. When we view every house or creature or elephant or animal as the same we go into a kind of explanatory system and begin to categorize these images. On the other hand, if we notice that each house is different in its own details and that each animal or creature has its own particularity or uniqueness or oddity, then we slow down, take the time to watch and look and carefully notice its particular actuality. The fourth core skill is patience. In order for images to reveal who they are, we must slow down and be patient. With patience, images will reveal what they offer from the inside out. Working with these core skills we get interested in the “visitation” of the living images. We are asking the question, “Who is visiting now?” rather, than being hell bent on determining, “What does this mean?” Our insistence on “getting to the bottom of things,” and finding the “correct answer” or “meaning” renders the image lifeless.

Jeanne: That’s a lovely way of answering that question.

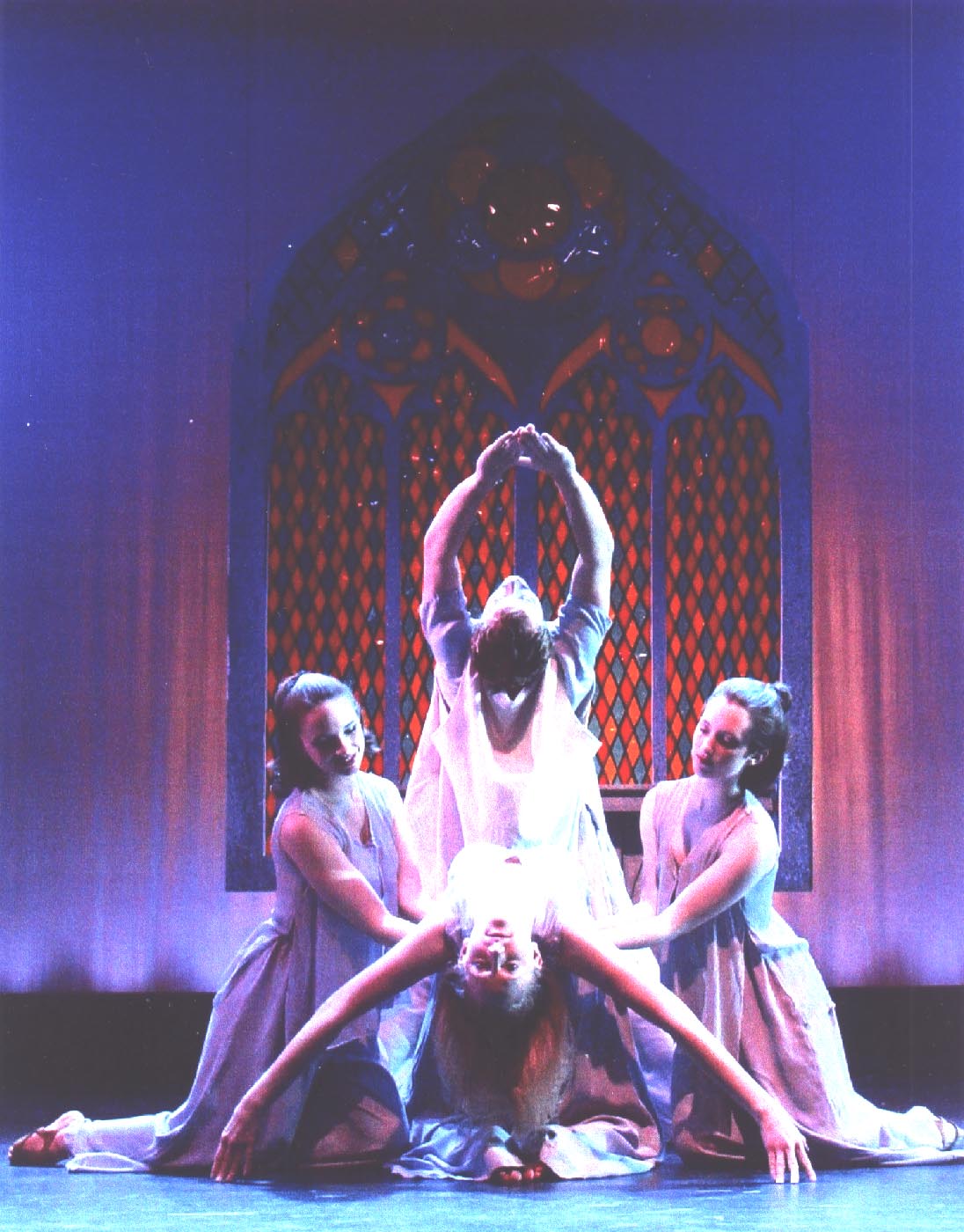

Steve: It’s similar to the artistic process, I would imagine. When I watch you dance, for example, one way is to rehearse the steps and know the choreography; and that’s wonderful, helpful. Another way is to know the choreography and then in performance to allow something else to move through and fill the body. There’s a certain spontaneity that goes with the discipline. It makes all the difference. When you watch, some people fill the room with their resonant quality. They originate from a deeper source. Other people are moving through the action but you don’t have a sense of their depth of presence. And the same is true, I find, when working with a dream. When we work out of the deeper sources, something comes forward that otherwise would not.

Jeanne: What is your feeling about working with dream images to create poetry, haiku, or dance?

Steve: Well, I think that the psyche itself is poetic from the beginning. So, there’s a poetics of psychic reality; it’s not as linear or rational or literal as we might imagine. Rather, there’s a certain kind of poetry that’s always going on. After all, the dreams, when they come forward, aren’t in paragraphs or sentences. They present themselves in imagery, and often in story, gesture, or sound. A certain quality of metaphoric elaboration is already a part of the enactment. There’s a poetic quality from the beginning. To meet the poetic psyche in the way of a poem is very different than to meet it as a literary critic, for example. I think to appreciate that a poetic quality is already a part of the dream is to listen and allow the dream to live in its own rhythm, its own complexity, and its own intelligence. It’s just remarkable to imagine that every day there are a thousand images available to depict any particular dream motif. The dreaming psyche “chooses” a particular set of images and after creatively combining them, putting them together, a story comes forward that at first glance often makes no sense whatsoever to the rational mind. Yet, once you start listening with a poetic ear, something altogether different happens. It’s as if the poetry is already there presenting itself for those who have metaphoric ears to listen and aesthetic eyes to see. And like seeing through a looking glass, each dream is multi-leveled like a parable, commenting on circumstances of the day, on my life history, and on the archetypal themes that are running through it. In addition, it’s picking up on images or expressions from the world’s psyche or the world’s soul. All that’s happening and can only happen as a creative presentation. Otherwise, every dream would be two volumes of written narrative. Like a great painting, it captures us and opens us in multiple ways, which is what I think dreams are meant to do. They come forward and, when we tend them, rather than interpret or analyze; they engage our imagination. Like an extraordinary painting or a great piece of art or a remarkable piece of theatre or dance, dreams resonate with poetic depth. That which is to be revealed will become known if we allow ourselves to take a step back and allow them to work on us as much as we work on them.

Jeanne: One phrase that has resonated with me for a long time that you often say is that “the body is always dreaming.” Long before I ever started studying dreamwork, I was using dance as a way of working with my dreams, not to analyze or necessarily even understand, but to make the image alive for me. I just want to hear how you are now with the idea that “the body is always dreaming.”

Steve: I have a couple of ideas about that. As I have suggested, I don’t think dreams originate in our rational mind. They originate from a deeper source. One such source is the body. When we experience an upset stomach, or a place in our back where we’re feeling tight, or the onset of a cold or flu, or more seriously, something like a cancerous growth, the dreaming psyche is going to pick up those symptoms and most likely present them in the imagery of dreams. On that level, the body is always dreaming. So, when we listen to dreams, we are always listening to the body talk about itself in one way or the next. On another dimension, images themselves come with body. They are alive and active and they walk about. They breathe and have presence and pulse. They certainly are not incarnate like our bodies, but in an imaginal context—in the world of dream—they’re very interactive and very embodied. In that context embodied images have emotion or feeling. It’s not only we who have emotions in response to the image. Images will come with emotions to begin with and then in turn create an affect inside of us. It’s simply a different way of appreciating dream and it’s not esoteric. It’s very “just so.” When we take the time to listen to dream or to watch the actuality of the dream presentation, we see images walking about affecting one another—one figure impacting another figure. Embodied images are filled with emotions and feelings; and they tend to evoke our response. We then can allow our bodies to move with gesture or even with dance to greet the image. In a curious way, in those moments we are interpreting the dream—not through words or through our mind-—but through our bodies. We’re meeting the image body of the dream with our bodies. That kind of interaction I find quite important and useful.

Jeanne: How about those dreams in which—not people—but animals are communicating with us?

Steve: Our tendency is to interpret the animal or capture it or dissect it like you would a butterfly; put it in the case and label it. The animal means an in-law or the animal means an aggressive creature like a boss that’s overly aggressive or it may be a partner who is overbearing. Our tendency is to attribute personal characteristics to the creatures. There’s probably some value to that, actually. In addition, though, the animal has its own reality, its own autonomy, its own independence, and its own presence. In all the stories when we follow the animal something out of the ordinary is bound happen. When the creature comes and you follow, we find our way “back to Kansas.” When ET comes, something “out of this world” reveals itself. Animals forever take us on a journey, are important guides through unknown terrain, or serve as important teachers. Sometimes they even come to us as ancestral spirits. So, I always suggest taking great care to listen to the intelligence that lives in the animal and taking the time to follow the animal. If you follow the animal, something unexpected tends to show up.

Jeanne: You have a book coming out quite soon.

Steve: Yes, in the first part of next year.

Jeanne: What can you tell us about it?

Steve: The book is called Dream Tending, and it documents the approach that I use with dreams. It is woven around a personal story. There are some personal reflections about my experience and my relationship to dream and how it has affected my own life. There are many teaching points. So, it covers the primary ideas that anchor Dream Tending. It talks about the concept of the “living image.” The book has a full chapter about tending nightmares. It has a section about tending images as medicines for work with physiological aliments and illness. Part of the book describes in detail Dream Council, which is a way of sustaining relationship in a long-term way with dreams. And too, the book talks about the World’s Dream, an eco-psychological approach to dream work. In addition to the teaching points, there is an experiential component, so that people who are reading the book will have an opportunity to work with their dreams. There are particular exercises or methods that are presented—tools that are embedded all throughout the text that will help people work with their dreams and have an actual experience of what tending to a dream is and how that is different than simply interpreting or analyzing a dream. When tending a dream, there is an immediate correspondence to the challenges presented by daily life. In fact, in the book I have a section on the practical applications of working with dreams. I offer skills, elaborations, and case examples of working with dreams in the workplace, in intimate love relationships, in relation to money, and vocation. So, there are a lot of practical applications of how to work with this material in relationship to issues of everyday life.

Jeanne: How does the book play into the huge following of people who have taken the Dream Tending classes and those who are interested but haven’t yet participated?

Steve: The challenge of the book is to do two things. One is to really put a lot of what I’ve been working on for now over thirty years in one place, so that people will have a foundational text or a touchstone out of which to continue and sustain their practice of dream tending. To work with dream, to tend dream, is a life practice as much as it is a therapy. It’s a way of being in the world, oriented and anchored in dream, in a relationship to dream. So on one hand, I think it is going to be very helpful and useful for those who have worked with me and worked with the art. In addition, the book is written in such a way that a person who has never been acquainted with my work or has never worked with dream will have an opportunity to move through the book gradually and find the methods and the tools that they might find useful in developing a relationship with a dream. So, it’s really working on two different dimensions at the same time.

Jeanne: You also have a DVD out now. My experience of it is that it is very beautiful.

Steve: Yes. There’s a DVD—about an hour long—and that’s about the Dream Tending method and it depicts it in visual form. Then, there’s a CD series through Sounds True that’s just been reissued. It’s a six CD set on Dream Tending that provides the methods and the tools and examples and it’s in narrative. So, between the movie and the CDs and now the book, there should be a lot of information as to how to work with dream from this point of view.

Jeanne: Where do you think your work will take you now that you have this concrete piece of it complete?

Steve: I’m doing a couple of things that I find most exciting. I’m working with at risk teenagers, actually, working with dream and working with this approach to dream; working with kids that have been in and out of jail and having a hard time with drugs, school, or a really difficult time in family life. Many of them are coming from juvenile hall, so you would not think that dreams would be the medium that would be useful. It is surprising, and quite frankly, deeply satisfying to work with a group of 20 or 30 teenagers in each session who are pretty hardcore by any of our standards; and yet, you introduce image or you introduce the idea of dream and imagination gets ignited and we’re talking story and all kinds of things start coming forward. The liberation to engage the most tortuous of feelings and life circumstances is remarkable. We are in deep conversation for hours on end. So, I’m very interested in doing more of that. I’m also working with a project of the United Nations, working with dreams in relationship to international environmental policy formation. Bringing dream work to this initiative, the development of an Earth Charter, is instructive because with dream we start at the place that honors multiple perspectives. As we know, embedded in the imagery of dreams many points of view present themselves from the get-go. Dreams are an under utilized resource and a little known source of intelligence in the world of diplomacy. We get so fixed in our positions; and yet, when dream or image or story comes forward, we’re placed, at once, in imagination and we’re looking at things from many different angles. So, I’ve introduced dreamwork into a number of forums now: working with the policy development and also working with leaderships groups at this level. What’s been gratifying for me is bringing groups of people together that otherwise would be in conflict. I have found that dreams are a way into what lives at the core of our humanity. When dream work comes into the room so does compassion, understanding, empathy, and a willingness to work through our differences and find common ground.

Jeanne: One question that was offered by the editor of Dream Network Journal was any relationship you might find between the dream and the political environment right now as we approach the election.

Steve: I was just in Europe and talking about the current presidential election. I was offering lectures from a depth psychological perspective about Americans’ reaction to the war in the Middle East. I was talking about this in relation to dream. What came back from audience after audience was a powerful response to the political dialogue unfolding in the United States. The power of the imagery is vivid and vital. The interest, the curiosity, more importantly, the passion that gets constellated around what is happening in this country is being experienced as nothing less than a revolution of thought and mind. What is being sparked is way bigger than what most Americans can imagine at the moment. And of course, that has to do with the Obama phenomenon and the presidential election. People are responding strongly overseas, just as they are in this country. I suspect it is similar to what happened when the presence of Lincoln or FDR or even for that brief moment Kennedy was at work in the imagination. What’s being evoked is a revolutionary impulse. Folks were not telling me that they were seeing Obama or McCain as literal figures in their dreams, but I have picked up, again and again, a certain kind of rising tide of passion. I’m not sure it’s linked only to this particular election. It’s linked to something else that is operating in the Zeitgeist at the moment. On the one hand, there are images of liberation appearing more frequently in dreams. On the other hand, images of grief are also making their presence known. I think they go hand-in-hand. I think the new news is that in the United States, in our psychology, collectively, there tends to be a lot of grief that’s coming forward as well as the more obvious enthusiasm. Of course, the dream images of grief can be attributed to the war that seems to be never ending, to environmental concerns like global warming, or to the worries about the impending economic recession/depression, but it seems much deeper than that. It seems as if, in a curious way, in the psyche of Americans, there’s a grief over the Empire itself. We’re coming to terms with the idea that we are not any longer Number One on the planet. That fall from grace, the idea that other countries, other nations, are emerging, and we, as the dominant empire, are on the wane; there’s a kind of grief that comes from that. It creates a kind of numbness or a kind of denial. And, of course, when not fully conscious, then the dreaming psyche will pick that up. What I’m experiencing is not only dreams of liberation and other corresponding images of hope and desire that Europeans and Asians are having about America, but here in the United States, I am seeing a lot of imagery that depicts grief, dying and death. Our first response is to literalize these images. A figure dies in the dream and we imagine an aspect of our personality that’s dying or somebody in our world is in ill health or we’re dreaming of our own mortality. I think, collectively however, that there is something going on in the Deep Psyche that knows somehow that the global dominance of the American Empire is coming to an end. That’s what I would say. I think the Obama phenomenon, in some ways, is a response to that grief. I think that the political dreams of our day have as much to do with the process of dying as they do with the desire for change.

Jeanne: What else would you like to share? What have we not touched?

Steve: About 30 years ago, when I first started working with dreams, dreaming was very popular. Working with dreams was a popular phenomenon. I think it started all those years back with Carlos Castaneda and lucid dreaming, going back years now. There was a kind of curiosity in the interest of dreams. It was all the rage. Dream books were selling as soon as they hit the shelves. The field of Depth Psychology was coming forward through the Human Potential Movement. The work of Jung was beginning to take hold in this country and other places. The mythology of Joseph Campbell became popular. There was a kind of move toward imagination and dream. Over the last ten or fifteen years, much of the popular interest vanished. People were not as interested. But in the last year or so, there seems to be a resurgence of fascination in dreaming and in the imagination in general. The imaginative processes are again capturing the curiosity of so many people. Everywhere from Oprah to late night radio, we’re beginning to hear people talk about dream and getting interested in dream. As I travel around the country, workshops are much more highly attended. So, I think there is a renaissance of interest at the moment. What I advocate is that people get into small dream groups. I know that for a long time that was frowned upon and people thought it was best only to work with dream one-on-one. But now, more than ever, I think there’s a kind of a call back to the earlier times in human experience where people gathered together in small groups and talked story and talked dream. We all don’t need to be psychoanalysts or trained therapists. It’s just okay to sit and tell about our dreams, to let the dreams get to know one another. The fear is that we are going to hurt each other; we’re going to get overly psychological. But if we don’t intrude or we don’t impose or we don’t leverage dream, we can just simply listen to each other’s stories. People have been doing that for thousands and thousands of years. I think it’s a way of making contact. It’s a way of accessing imagination. It’s a way of guarding against the era of too much programmed information and too many video screens. When I watch my kids and others kids, they’re in screen time so much of the time that they (we) lose contact with the spontaneous imaginative process that is indigenous to each of us. If nothing else, talking dream opens up story and evokes imagination. I think it’s a wonderful thing to see the return of an interest in dreams and a return to an engagement with the dreaming psyche. ∞

The interviewer, Jeanne M. Schul, first met Dr. Aizenstat at a DreamTending workshop, which was so inspiring that she immediately signed up for his professional training program. Then began her doctoral coursework in Depth Psychology at Pacifica Graduate Institute.