Eric Snyder: What, in your view, are the most significant benchmarks/ successes in terms of educating the public about dreams in the past 30-40 years?

Richard Wilkerson: In terms of dreamwork, the 1960s break-out into peer groups, the early books, the experimental dream groups, the networking newsletters and magazines like Dream Network Journal, the more formal ASD organization and conferences and finally the Internet.

The couch to culture break-out of the 1960s, where individuals began experimenting with the multiform encounter groups that were somewhat guided by the hope of liberation outside of traditional psychology and enlightenment outside of traditional spirituality, seems to me a big marker in the change of dream sharing. Before that time one had to embark on dreamwork quests within the confines of therapy, or to be invited into a rare esoteric spirituality group (Like A.R.E. dream research groups).

This evolution was fueled in the 1970s by researchers and their books. Writers like Patricia Garfield with Creative Dreaming, Ann Faraday with Dream Power, and Henry Reed’s Sundance Community Dream Journal synthesized the emerging ideas, techniques and experiments of the movement and put them into a media form (books and journals) accessible to the general public.

The 1980s might be called the Dream Movement Decade. The number of books on dreams and dreaming proliferated. The Dream Network brought dreamers ideas together from around the US and the world. The pioneers in dreaming got together and started the Association for the Study of Dreams, and dream groups could be found in all the US states and major cities. Lucid dreaming had moved from the category of the occult to science, and New Age spirituality reinforced the notion of the dreamer being the final authority on the meaning and value of their own inner experiences. Orthodox religious institutions that had persecuted people sharing dreams for centuries began to offer dream groups. The ASD Dreaming journal found its way into major educational libraries and international and regional conferences were held on a regular basis, bringing together anthropologists, scientists and researchers, clinical therapists, religious leaders, writers, and dream-inspired artists.

The 1990s saw the advent of the Internet and the ability for anyone who wanted to share dreams to quickly develop a group of peers from anywhere around the world and discuss their dreams. The number of people who are now interested in dreams has grown geometrically since the 1960s, and the educational outreach to interested individuals and groups has been greatly enhanced by the Internet and other networking organizations. The ability to network across the globe has advanced the feeling that dreams are a treasure crossing all national and religious boundaries. This has led to a sophistication in relation to dreams and dreaming that is unparalleled in history. There are many institutes, schools and organizations that study dreams in relation to science, anthropology, psychology, religion, the arts and humanities... and see dreams as a crucial part of these studies.

Eric Snyder: How do you see the ‘Dream Movement’ at this time?

Richard Wilkerson: Slowly spreading, interconnecting, very rhizomatic. The Dream Movement is difficult to capture as a whole at any one time and period. One of the defining characteristics of the movement has been the lack of defining characteristics. That is, dream folk tend to do a lot of their work on their own and this trend is manifested outwardly as well. Multiplicity of movement and plurality of progress follow along the polyvocity of ideas and polytheism of its spirit. A strong individualism pervades the dream movement culture. There are thousands of books, websites and groups, hundreds of organizations, and several schools with a dream focus, yet no real key texts, trends or manifestos as with other movements. One may at the same ASD conference find a presentation on benefits of dreamwork right along side a presentation about dreamwork being nonsense. One can find in a single issue of Electric Dreams e-zine an article by a postmodern philosopher on the random valuation in dreamwork alongside an article by a self-proclaimed guru on the dreams and enlightenment. This individualism is also the movement’s strength and a sign of the maturing tolerance and ability to hold together in one space many competing and opposing ideas. Some dream organizations, like ASD, do have ongoing mission statements but others, like BADG (Bay Area Dreamworkers Group), function more like interest groups online (i.e. they get together when there is an interest, and disband when there isn’t).

The movement is advancing most all of the original projects, and adding new ones which are beginning to delve into areas usually not considered as being the province of dreaming, such as politics. Dream activism groups use dreams to talk and discuss major collective issues of the day, and to plan activities that may take the future in the course or direction of the group values. Many dream groups since 9-11 have opened up the strictly dream-as-ego viewpoint and added the dream-as-worldself viewpoint.

While dreams are still a great mystery and science has barely opened the crack in the door between the dreaming brain and the dreaming mind, emerging research is offering new models of dreaming that haven’t been challenged since Aserinsky and Kleitman’s 1950s REM studies. These studies help dreamworkers to weigh and judge the various dreamwork theories. (Is the dream material all day residue, how much of the dream is influenced by physical forces, by psi forces, by psychological and spiritual forces and so on).

Eric Snyder: What do you envision or suggest that we, as individuals and collectively, create in the next 40 years? We’re looking for blueprints and/or roadmaps into the future, here.

Richard Wilkerson: Dreaming and dreamwork resist commodification, totalization and imprisonment. Dreaming and dreamwork promote liberation, play, health, and creativity. I expect this to be true for the next century as for the last.

What seems clear to me now is that dreamwork, dream studies, dream science, and dream-inspired works have proven themselves to be an important part of any project. This is true in two ways: the first in terms of wholeness and completion (no cognitive science is complete without an accounting of dreams, no spiritual or psychological work complete without dreamwork, and so on) but also as a friend and guide, inspiration and creative source.

In the short run, I see the dream movement providing continual support for individuals interested in dreams and that are ready or able to break out of the programming of everyday consensus reality. I feel this is happening at the level of therapists sensitive to dreams and educated in dreamwork as a practice of dissolving neurosis, as well as recreational dreamers who bring a sense of being and inherent meaning to the world of dreaming itself. This liberation is also made available by anthropologists who teach us about radically different approaches to dreamwork in other cultures. Our dream-concerned scientists remind us of the material forces that go into the many facets of dreaming. Our support of the development of peer and partnership paradigm grassroots dream groups, both online and off, will offer sanctuary and growth for those who want support in their journey. Our support of schools, publications and organizations that provide support for dreamers will, in the near future, make the pathway to dream awareness a less difficult and more networked, more diverse experience than in the past.

Looking further down the road, I would like to integrate into this speculation the notion brought up by Pierre Levy that “Humanization is virtualization.” In this view, the dream movement parallels a general trend that humankind has always been about building networks, moving ideas, integrating rich interconnections in rhizomatic fabrics of space and time. Dreamworkers are superb in these skills, and understand even at beginning levels of dreamwork how associations work.

In the first view of associations or connective syntheses, we can expect the Dream Movement to break into older patterns and flows of reality and make new connections; breaking up older organizations and connecting with people and their dreams in novel and productive ways. Using the older terminology, we might say that the future of the Dream Movement is about placing itself alongside as many other fields and practices as would be useful; dreams and health, dreams and creativity, dreams and business, dreams and spirit and so on. But this would just be a simple kind of expansion which the Movement is not likely to take, given its nature of subverting this type of expansionism and in its offering novel alternatives.

Rather, it's more likely that as the Dream Movement comes into contact with these organizations and regimes, they will change or metamorphosize in ways unexpected. Dream art, for example, will not just become a subcategory of types of art, but become aesthetico-political and/or polypsychotechnic movement that cuts between the lines of various traditional fields.

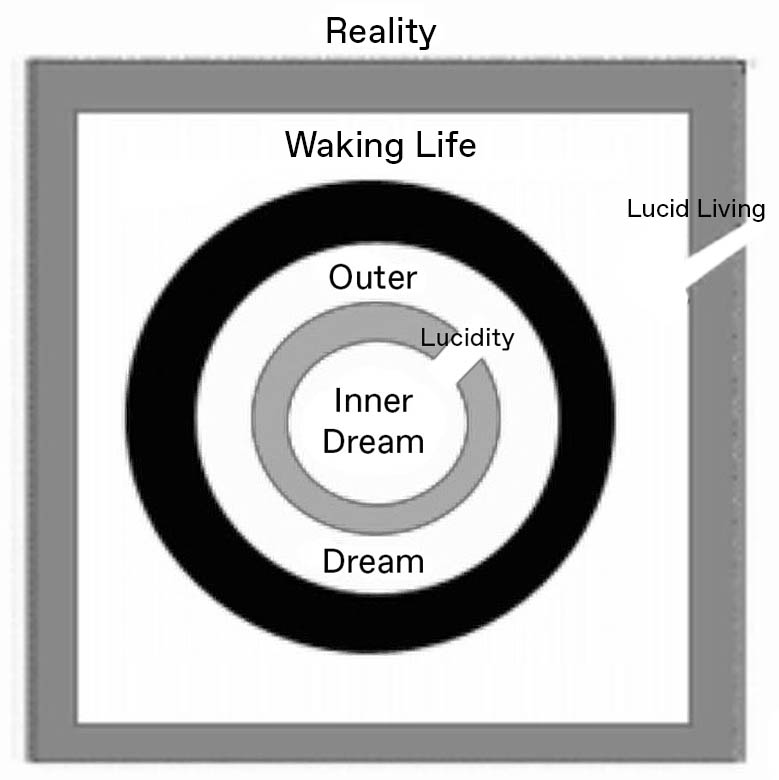

In the second view or level, where the Dream Movement in the future will provide new models for networking in virtual territory and disjunctive syntheses, we can expect some very novel transformations. Organic networks that are alliances of communicative communities — rather than hardwired circuits — will be distributed and connected by protocol rather than more restrictive bonds. The virtualization of the Dream Movement is not about its going online. In a few years the Internet will disappear. As Stephen Aizenstat mentioned at the 1999 ASD International Conference, soon the walls and floors will be alive and dreamworkers are positioned to help the world understand how to live this kind of virtual reality. That is, dreamworkers know how to move about in insubstantial material and create meaning and value. This is going to be vital as we move into living and working more and more in simulations, more and more in the hyperreal.

The Dream Movement has always been partially an exploration of virtual reality and its boundaries. This sensitivity to the bio-dramatic features of the virtual dreamworld will be needed in the future; first with computer-mediated virtual reality, and then with bio-logical and quantum fields of reality where the limits of what skin is and where our skin is will be stretched, where one senses friends around the globe, where presence and absence are measured in terms of emotional distances rather than miles.

In this sense, traditional dreamwork will be expanded to include not only the inner work and play of dreams of the individual for the individual, but then also carry outward what is learned and lived inwardly. The inner world of the dream has always been taken as a kind of communicative community; as we begin to live more in virtual space, we will see these skills transfer to the world itself. Is it not that the world will become dream or the dream the world. Rather, the skills and sensitivities of developing rapid rapport with other-ness and development of on-the-fly communicative communities — which prove to be so much of our inner dreamwork — will allow us to tend to the soul of the world in mutual embrace. ♦