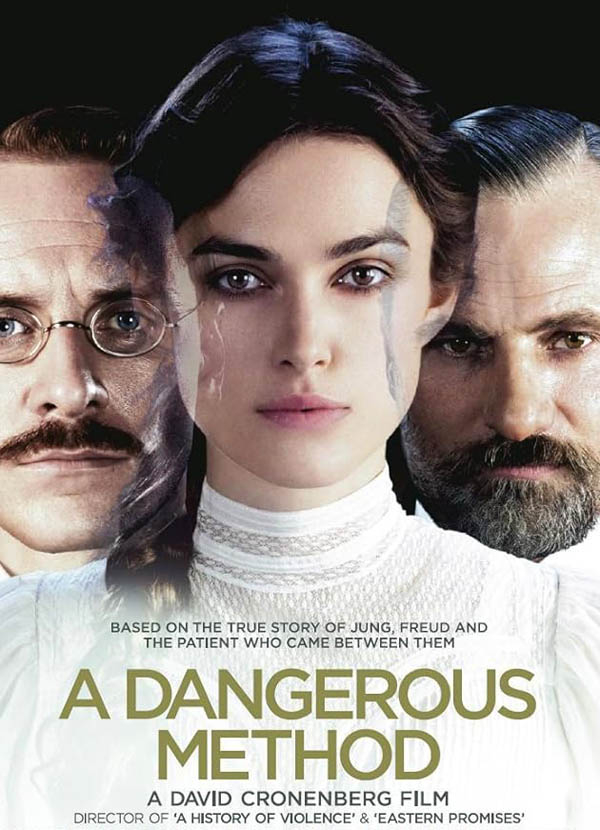

Most people familiar with the history of psychoanalysis will be well aware of the conflicted relationship that developed between its two founders, Sigmund Freud and Carl Gustav Jung. Moreover, now that Jung’s Red Book has been published, we can see in considerable detail how his journey into the unexplored realms of the Collective Unconscious followed closely upon the collapse of that relationship. David Cronenberg’s film explores this conflict from its origins, and places it within the context of Jung’s relationship with the brilliantly gifted but deeply troubled Sabina Spielrein, first his patient at the Burgholzli Asylum, then his collaborator, and eventually his lover. He makes this relationship the mainspring of the tension between the two men, as Jung first sought to deny its sexual dimension to his would-be mentor and father figure, but eventually was forced—indeed, almost blackmailed—into revealing it. The film explores in depth his inner conflict between the Protestant values of sobriety and restraint by which he was raised and his own libidinous urges. In the end, all three of the principals come across as more human as the result of their turmoil – though it is clear that Cronenberg’s strongest sympathies lie with Jung. Freud is depicted as being increasingly trapped in his own theories, unable to accept anything that goes the slightest bit beyond them; and Spielrein’s neuroses, while she has overcome many of their manifestations by the end of the analytic process, remain latent, just below the surface.

The film is deeply permeated with symbolism: Sabina is always shown in white; Freud always has his cigar (which, of course, is just a cigar!), and Jung eventually adopts a pipe. The musical score, by Howard Shore, borrows heavily from Wagner’s epic Ring of the Niebelungen, which is also frequently mentioned in the plot. For those familiar with the Ring, this provides a set of internal references, which augment the drama. For example, as the ocean liner bringing Freud and Jung to the New World approaches the southern tip of Manhattan, we hear the “Entry of the Gods into Valhalla” from Das Rheingold. More subtly, the music given to the earth-goddess Erda accompanies Sabina’s explanation to Jung of her theory of sexuality as surrender, which is diametrically opposite to Freud’s views, just as the theme itself is an inversion of the masculine Wotan’s spear theme.

The emphasis on the Ring also provides us with a context in which to understand, not only the film, but also where his explorations were shortly to take Jung. The film stops just short of the start of the Red Book, in 1913; it refers to Jung’s plunge into the unconscious only in an afternote. But in one of his earliest dreams recounted therein, he and a mysterious dark companion shoot the Wagnerian hero Siegfried in the back – the suggestion is made in the film that the ideal man Sabina is searching for is the Siegfried archetype. Thus, it is ironic in the extreme that another afternote tells of her murder at the hands of the Nazis when they invaded Ukraine in 1943. But there is more than this: Freud at one point in the film refers to Jung as his “son,” which clearly intensifies the Oedipal conflict that arises between them. In the Ring, Siegfried is the son of Sigmund – so it is his own filial relationship with Freud, which Jung is killing in the dream.

In a pivotal scene in the film, Sabina takes the initiative and kisses Jung on the lips as they sit on a park bench. He responds by remarking that ordinarily it is the man who initiates sexual contact. She replies that she believes that there is something of the masculine in every woman, and something of the feminine in every man. Have we here the origins of Jung’s concept of anima and animus? If so, this would certainly help to explain another dream encounter early in the Red Book: he meets the prophet Elijah and his daughter Salome, who attempts to seduce him. Jung’s initial extreme aversion to the Salome f igure is difficult to explain unless she is a back reference to something in his experience. By this time he had not yet acquired the reputation of “the Bull of Zurich” and was struggling to maintain a monogamous relationship with his wife Emma. But it is Salome who explains, and exemplifies, the archetype of the anima to Jung in his dream encounters with her. And if Sabina is Salome, surely Freud’s role – at least in this early turn of the spiral – is that of Elijah, the inflexible Old Testament prophet.

The film is gloriously shot, with views that seem to be on location in Zurich and Vienna, though only the Viennese location is mentioned in the credits. The house, which Jung built, is strongly featured and perfectly rendered, within and without (having visited it last summer, I can attest to this, though it was a bit startling to see the stately boxwood trees which today line the driveway from the road as they were in 1909, only a few feet tall!). The road which Sabina’s car motors down at the end of the film is recognizable as the one which leads to Jung’s famous Tower, though that itself is never mentioned – for its construction lay in Jung’s future.

I strongly recommend this film to any who are interested in Jung, Freud, and the origins of the psychoanalytic method. It demonstrates this method in some detail, with dream accounts (though Freud refuses to share his own dreams with Jung, for fear of losing his “position of authority”). The performances of the three principals are excellent. It is well worth seeing!