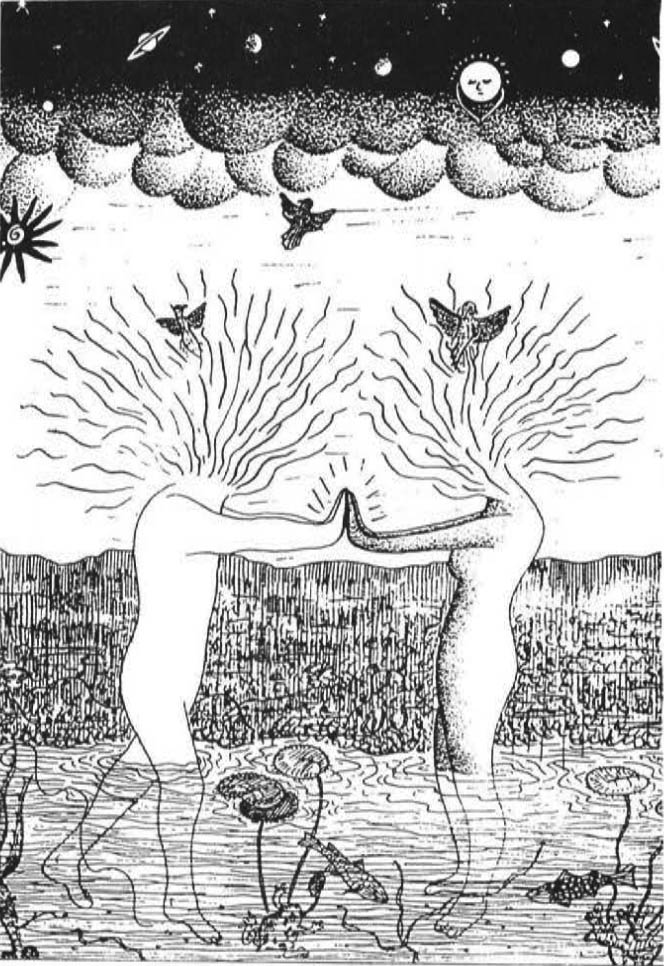

“When you harm Nature, you harm yourself.”

I first heard those words nearly twenty years ago, in a dream. They have haunted me ever since. In that equation’s utter simplicity, it seems to me, a deep ecological truth about relationships emerges.

In the dream, I stand on a steep sloping river bank of exposed dirt and mud. A friend and I watch helplessly as a lone figure proceeds to cut down the last standing tree on the desolate river bank. As I observe the final bit of green life lean sharply and tumble to the barren ground, an unspeakable sadness rises within me. At that moment, my friend says solemnly, “When you harm Nature, you harm yourself.”

On one level, it was ironic to hear these words from my friend, since in waking life, he graduated from the University of Chicago with an MBA and firmly believed in the “Chicago School” of economic thought, which held that the free market would provide for everyone’s needs by properly valuing all items, according to the laws of supply and demand. But having canoed with my friend as a Boy Scout, backpacked with him across wilderness mountain passes in Colorado and New Mexico, and sipped cold water from alpine streams, I knew there was another side of him that valued the beauty and great harmony of nature.

As an adult, I tried to discover what economic value he and the Chicago School’s free market system placed on nature. What was the value of a healthy environment? What was the value of a well functioning ecosystem? How did this economic approach calculate global sustainability? Like many discussions with economists at that time, I found that a properly functioning ecosystem seemed a “given.” We did not have to be concerned about it; the natural world had been built into the equation as an economic assumption.

Yet in this dream, my friend provides an answer with a new and startling economic equation devoid of assumptions and givens. When you harm Nature, you harm yourself. Suddenly the fundamental economic principle of the environment seemed clear: When you deplete nature, you deplete yourself. When you hamper nature, you hamper yourself. When you threaten the proper functioning of nature, you directly threaten yourself. Subtracting from nature, subtracts from you. Enhancing nature, enhances you. Economically and quite practically, my dreamt equation made explicit what economic equations do not: our individual and collective well being is intrinsically connected to Nature’s micro and macro well-being.

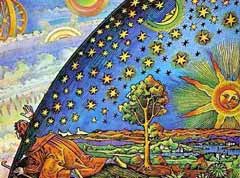

Somewhere in history, modern man began ignoring that direct connection with physical nature. Similarly, the rarefied world of economic thought and philosophy dismissed it too. Yet the deeper, archaic, unconscious part of my self, accessible in dreams, still carried the knowledge of this ancient economic equation. A subconscious portion of me knew what had been tragically learned on Easter Island and elsewhere: “When you harm Nature, you harm yourself.”

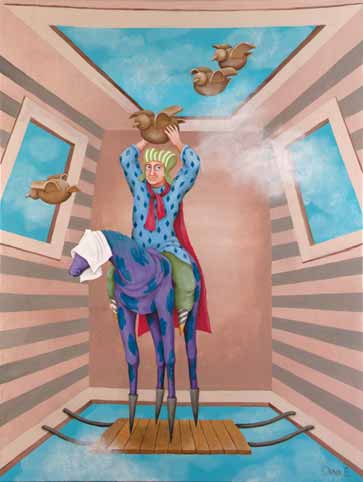

In dreaming, we possess a connection to this older and wiser portion of our being, which can remind us of ancient truths and guide us to creative realizations and actions—if we do not ignore it. In the final chapter of my recently released book, Lucid Dreaming: Gateway to the Inner Self, I relate an interesting dream in which a tall, regally dressed man stopped me and asked me a simple question, “What book do you hold in your hand?” Unsure, I brought the book in front of me and read the title, “Dreams: God’s Forgotten Language by John A. Sanford.” Then suddenly, it dawned on me that I had this book on my book shelf but had never read it. I became lucidly aware... ecstatic.

Upon waking, I pondered the idea that the unconscious portion of my larger self had knowingly and purposefully called this book to my attention as important. But why? In the book’s final chapter, “The God Within,” I find one of the possible answers in Sanford’s conclusion:

“We are not only conscious; we are also unconscious. Unconscious psychic reality is as real and substantial as is our conscious life. It expresses its reality in a hundred ways, one of which is the dream. The center of our conscious life is the ego, the center of our total psyche is the self, which seeks to express through our consciousness the totality of our nature.”

By attending to our dreams, we have one means to attend to “the totality of our nature.” Without the connection to dreams, we can easily forget and ignore our broader nature and become trapped in an ego-centric and finite world.

With Sanford’s perspective, the wider circle of interrelationships becomes apparent. Not only, “When we harm Nature, [do] we harm ourself,” but when we ignore and deny the unconscious, we lessen ourselves. We lose touch with our inner nature. It is our inner nature that reminds us of our ancient connections to Nature, others and the larger self—the broad circle of being. The gift of dreaming is the gift of that connection. Through honoring that connection, we can find a way.

When you love Nature, you love yourself.

∞